In this post I link to Hypoxia During Upper Endoscopy: A Serious Problem and a New Solution, NOVEMBER 1, 2019, by René Miguel Gonzalez, MD from Anesthesiology News.

I believe that the article linked to below is, despite the title, of great interest to all clinicians

Here are excerpts:

The Problem

In 2017, Goudra and Singh wrote: “The growing popularity of deep sedation for UGI [upper gastrointestinal] endoscopy has created immense challenges to anesthesiologists. Gastroenterologists have clearly benefited from deep sedation. It allows performing complicated procedures with relative ease. However, research suggests that management of the airway is anything but routine in this setting, and failure to rescue an airway at an appropriate time has led to disastrous consequences.”1

See The HHS Report On Joan River’s Death Following Her Procedural Sedation

Posted on February 5, 2017 by Tom Wade MD

Returning to the excerpts:

Case 1

A 57-year-old patient, weighing 91 kg and 183 cm in height, with a medical history significant only for treated hypertension and a remote smoking history, presented for an outpatient UGI endoscopy and a colonoscopy. Vital signs were normal. Monitors and a combined nasal cannula/nasal capnograph at 6 L/min oxygen (O2) were applied and propofol sedation was administered. Shortly after insertion of the esophagoscope, the patient desaturated profoundly to below 50% on pulse oximetry and developed bradycardia and premature ventricular contractions, as well as episodes of ventricular tachycardia.

Code Blue was called. The endoscope was removed, positive pressure ventilation with 100% O2 via an Ambu bag initiated, IV lidocaine administered with ventricular ectopy resolved, and after several minutes of ventilation, O2 saturation reached and remained in the 90s. The esophagoscopy and colonoscopy were canceled. The patient gradually woke up and was transferred to the emergency department for further observation and evaluation. Lab studies including cardiac enzymes were normal, and the patient was discharged home six hours later—a bit tired and sleepy but in stable condition. No formal neuropsychometric testing was performed.

High-Risk Anesthetics

Sedation for upper endoscopies, even “simple” esophagogastroduodenoscopies, should be considered potentially high-risk anesthetics for a number of reasons. First, they are, by definition, “reduced airway access” cases, as the airway is shared by the endoscopist and the anesthesia provider, and because the patient is typically placed in the lateral, semi-prone or prone position, facing away from and greatly reducing the anesthesia provider’s access to the airway. Teeth can be dislodged and the tongue can be pushed into an obstructing position by the bite block or endoscope.

High-Risk Patients

High-Risk Environment and Human Factors

Many upper endoscopies are performed in procedure rooms and endoscopy centers with no access to an anesthesia machine in case of an airway emergency, and are in locations remote from the backup resources available in the OR suite (i.e., non-OR anesthesia, or NORA).

Upper endoscopies often require very deep sedation bordering on general anesthesia to suppress the potent gag, cough and laryngospasm reflexes, especially with initial insertion of the endoscope, and particularly in younger, healthier patients. Subsequently, the level of procedural stimulation—and thus, depth of sedation—can vary suddenly and significantly. Regardless of the specific sedative agent(s) used, deep sedation invariably leads to decreased respiratory drive and relaxation and collapse of the upper airway, particularly in patients with sleep apnea or who are obese, and in small or very ill patients with decreased baseline muscle tone.

Simple Math: Foreign Body Obstruction

It should also be appreciated that upper endoscopies are, by definition, foreign body obstruction cases, as a large foreign body, the endoscope, is placed into the aerodigestive tract, often producing near-total or even total upper airway obstruction.

Limitations of the O2 Delivery System

One of the biggest challenges in sedation for UGI endoscopy has been the limitation of our supplemental O2 delivery system. The use of traditional O2 face masks for upper endoscopy has been precluded by the fact that the mask impairs access to the mouth for the endoscopist. As a result, the mode of O2 delivery most commonly used is one of our least effective: a nasal cannula, or insufflation via an oral catheter.

As a result of the above challenges and limitations, hypoxia—sometimes profound—during upper endoscopy has perhaps come to be accepted, and even tolerated, as an inherent risk of upper endoscopy under sedation.

A New Paradigm Based on an Old Concept

Because airway management during upper endoscopy under sedation is, by its very nature, high risk, it should be approached much as we approach patients requiring general anesthesia in the OR—by remembering and using the time-tested principles of “safe apneic time” and “maximal preoxygenation.”

Apneic time is defined as the time from when the arterial O2 saturation drops to below 90%, into the steep portion of the hemoglobin–O2 desaturation curve, where it rapidly approaches critically low levels. In healthy adults breathing room air, safe apneic time is less than one minute.4 Morbidly obese patients and patients with decreased capacity for O2 loading (e.g., patients with anemia, pulmonary disease, decreased cardiac output) or increased O2 demand (patients with fever or in a hypermetabolic state) can desaturate much more quickly.5-7

It has been established for decades that the simple technique of maximal preoxygenation can significantly prolong, or even triple, the safe apneic time.5-7 In a classic 1999 editorial in Anesthesiology, Benumof wrote: “The purposes of maximally preoxygenating before the induction of general anesthesia are to provide the maximum time that: 1) a patient can tolerate apnea, and 2) for the professional to solve a cannot-intubate/cannot-oxygenate situation. Moreover, because a cannot-intubate/cannot-oxygenate situation is largely unpredictable, the desirability to maximally preoxygenate is theoretically present for all patients.”7

Benumof vigorously espoused maximal preoxygenation whenever possible. Preoxygenation has become standard practice for many practitioners prior to all general anesthetic inductions.5-7

Maximal preoxygenation is not equivalent to simply reaching 100% saturation on the pulse oximeter; it is a much more thorough O2-loading process. There are several accepted methods of effective maximal preoxygenation.4,7,8 All require high-flow O2 through a well-fitting O2 mask. The originally described technique consisted of five minutes of tidal volume breathing through a high-flow O2 mask. However, this is rather time-consuming and therefore impractical. An equally or more effective and efficient technique is the “8 DB/60 sec” method (eight deep breaths over 60 seconds) described by Baraka et al.7,8

Benumof’s logic and argument for maximum preoxygenation, which has served our patients so well for decades in the potentially high-risk situation of induced apnea in the OR, should be extended to patients undergoing UGI endoscopy under sedation, particularly if this can be done simply and cost-effectively.

A New Device

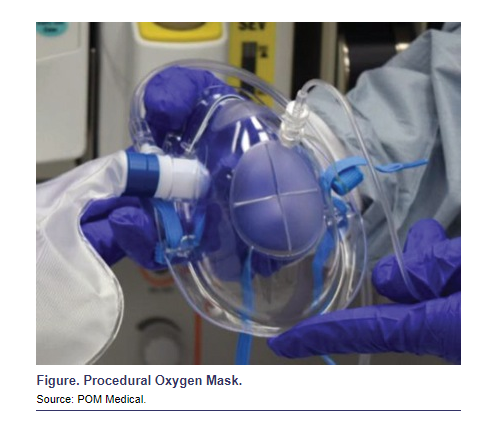

In recent years, there have been several O2 masks and other devices designed specifically for UGI endoscopy procedures.1 One of these, the Procedural Oxygen Mask (POM Medical), is a clear plastic mask that resembles the traditional familiar clear non-rebreathing O2 mask with an O2 reservoir bag, except that it includes self-sealing oral and nasal endoscopy ports and a capnography sampling port (Figure). The Procedural Oxygen Mask achieves the triple goal of the following: 1) providing reliable FiO2 delivery of 0.90 to 0.95 at O2 flow rates of 10 to 15 L/min when the included O2 reservoir bag is used, 2) allowing easy access to the nose and mouth via the self-sealing endoscopy ports, and 3) providing a continuous capnography sampling port. The mask can be connected to any standard O2 flowmeter.

The high FiO2 levels provided by the Procedural Oxygen Mask allow effective preoxygenation to be achieved efficiently and routinely prior to the start of sedation and endoscopy, and for higher FiO2 levels to be maintained throughout the case compared with nasal cannulas.

Since the incorporation into my practice nine months ago of routine preoxygenation with the Procedural Oxygen Mask for all UGI endoscopies, I have not had a single case of profound or prolonged O2 desaturation. In fact, the new normal using this technique is that O2 saturations remain in the high 90s throughout the procedure. A suggested preoxygenation protocol is described in the Table.