In this post I link to and excerpt from Assessment and Management of Toxidromes in the Critical Care Unit [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] . Crit Care Clin. 2017 Jul;33(3):521-541.

The article well summarizes diagnosis and treatment of the following:

- Anticholinergic Toxidrome

- Cholinergic Syndrome

- Sedative/Hypnotic Toxidrome

- Opioids Toxidrome

- Sympathomimetic Toxidrome

- Serotonergic Syndrome

- Neuroleptic Syndrome

And here are excerpts:

GENERAL APPROACH

Because the brain is the organ most commonly affected by acute poisoning, any patient whose behavior, level of consciousness, or established neuropsychiatric baseline are disturbed should prompt concerns about toxicity.4 From the standpoint of central

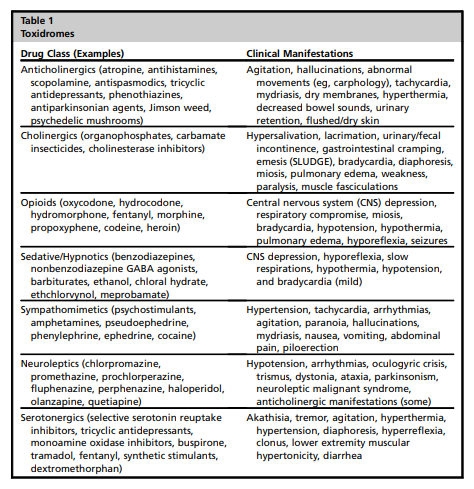

nervous system (CNS) function and diagnosis by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the presence of delirium is therefore a major reason to suspect a toxic etiology.Certain constellations of signs and symptoms, commonly called toxidromes, may suggest poisoning by a specific class of compounds (Table 1). The findings represent direct physiologic manifestations of the pharmacology of the agents in question, thus providing objective clinical data about the status of the patient and what has been ingested. Recognition of such patterns can be informative, but clinical pictures are not always so obvious. Polydrug overdoses may result in overlapping and confusing mixed syndromes.

Nevertheless, recognizing the dominant features of particular classes of pharmacologic toxicities can be a vital diagnostic and therapeutic starting point to psychosomatic consultation in the ICU.

TOXIDROMES

The toxic syndromes most frequently encountered in the emergency and ICU setting are detailed in the following sections. The causes vary, with anticholinergic toxicity, sedative

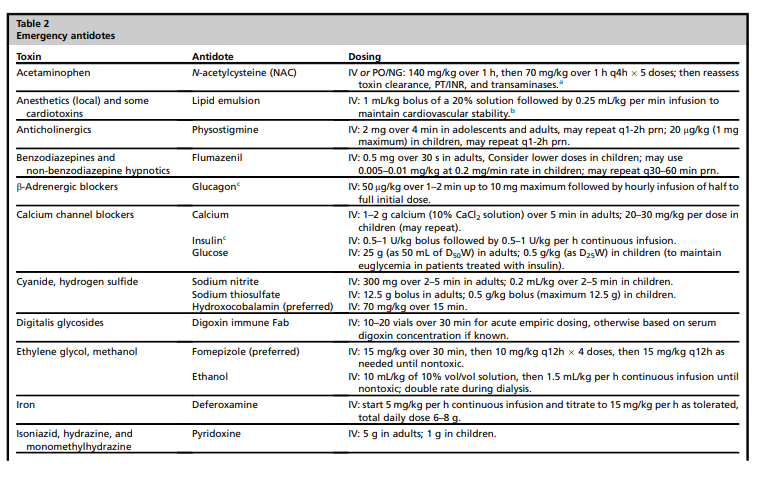

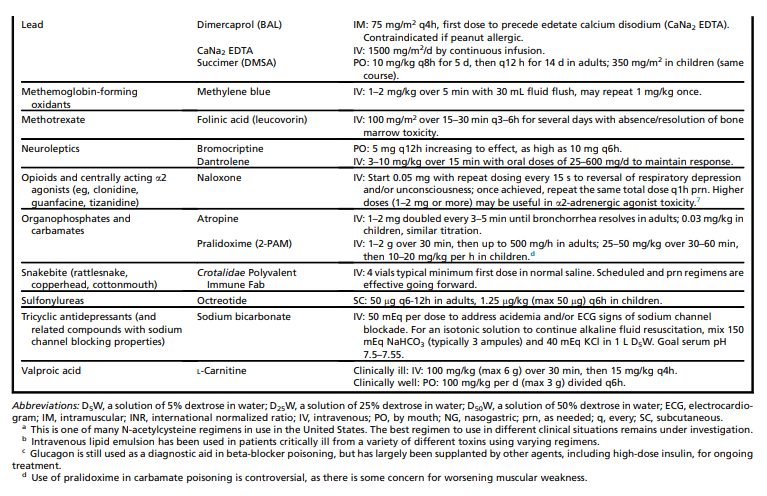

toxicity, and serotonin syndrome being common after suicidal overdose, cholinergic and opioid toxicity often being accidental or secondary to a recreational drug misadventure, and almost any syndrome potentially resulting from iatrogenic interventions. The most commonly used antidotes for these conditions, and for other toxic states not discussed in detail, are provided as a reference for the ICU psychiatrist in Table 2. Their specific indications are discussed under each toxidrome subsection below.

Anticholinergics

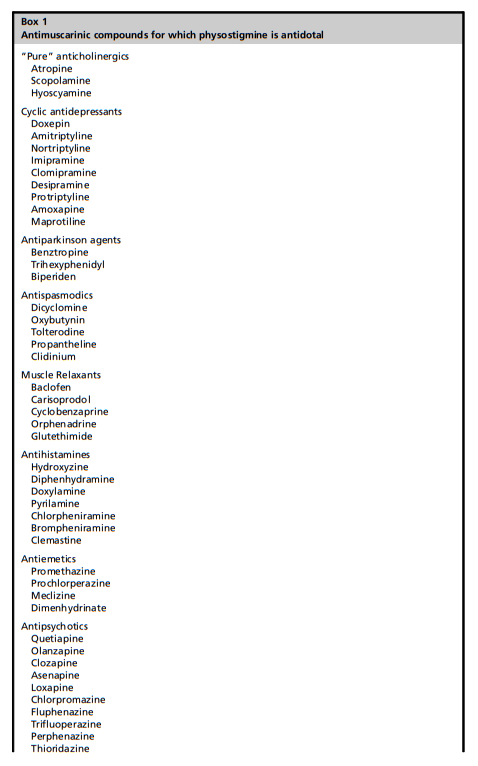

The anticholinergic syndrome occurs frequently because many common medications and other xenobiotics have anticholinergic properties. From sleep aids to muscle relaxants to antipsychotics, almost any medicinal compound whose generic moniker ends in “-pine,” “-zine,” or “-amine” has the potential to disrupt cholinergic function in the CNS with resulting delirium.

Deep tendon reflexes are often hyperdynamic, with a few beats of inducible clonus not uncommon. Other peripheral effects also are observed, but because most anticholinergics are lipophilic, the impact on brain function may be much more evident than effects on other organ systems. Inhibition of secretory functions of the integument can yield dry mouth, flushed skin, and impaired heat dissipation, so undressing behavior in a

state of confused discomfort is common.9 Suppression of cholinergic inhibition of heart rate may produce tachycardia. Unopposed sympathetic drive of the ciliary apparatus produces pupillary dilation.The duration of CNS effects typically exceeds that of peripheral symptoms10 due to the chemical preference of the toxins for fatty tissues and their slow diffusion back out of the central compartment once they have accumulated there.

Most patients recover with removal of offending agents and supportive therapy, but delirium may last for days after an acute overdose of anticholinergics, and considerably longer if medications that contribute to the problem continue to be administered.

Physostigmine may be a useful diagnostic tool and may serve as an efficacious antidote to rapidly target the cause of delirium.

[Onset of physostigmine is] within approximately 15 minutes of an intravenous (IV) dose. However, the antidote is relatively short-acting, with a plasma cholinesterase inhibition half-life of less than 90 minutes.11 Therefore, even though its lipophilicity may prolong restorative effects in the CNS, repeat dosing of physostigmine is typically necessary in the setting of severe anticholinergic toxicity.

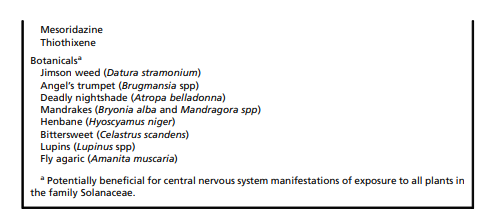

Physostigmine is indicated in patients with anticholinergic delirium caused by a variety of compounds from prescription medications to botanic hallucinogens (eg, Jimson Weed) (Box 1).

[See pages 6 and 8 of the PDF for details on the safe use of physostigmine.]

Cholinergics

The cholinergic syndrome is uncommon, but important to recognize because lifesaving treatment is available. Cholinergic toxicity produces a patient who presents “wet,” as opposed to the anticholinergic syndrome, which often causes the patient to be “dry.”

The wetness is manifest by profuse sweating and excessive activity of the exocrine system, often accompanied by vomiting, diarrhea, and urinary incontinence. The mnemonic “SLUDGE” highlights specific elements of the syndrome: salivation, lacrimation, urination, defecation, gastrointestinal cramping, and emesis.

The CNS (eg, confusion, seizures, coma) and skeletal muscles (eg, weakness, fasciculations, hyporeflexia) also can be involved, so the neuropsychiatric examination is important in diagnosis.

Cholinergic excess is frequently caused by accidental organophosphate or carbamate pesticide exposure, which may occur through dermal contamination.18 Such commercial/industrial agents and cholinesterase inhibitors used therapeutically for dementia can be used in suicide attempts, as well.

Cholinergic effects also are the cause of toxicity from “nerve gases” like sarin and from mistaken ingestion of Clitocybe and Inocybe mushrooms.

A not uncommon scenario of milder toxicity (but presenting with delirium) is accidental self-poisoning by a patient with dementia who takes repeat doses of a cognitive-enhancing drug due to forgetfulnessabout medication adherence.19

Mild forms of the toxidrome can be managed with discontinuation of offending agents and/or resumption of tapering doses of the overused anticholinergic drug, with supportive care.

Recognition of critical illness should prompt the use of atropine (or perhaps glycopyrrolate if CNS manifestations are not significant) and, in some cases of severe toxicity, the cholinesterase regenerator pralidoxime*. 21

[*Link is to Medscape Reference.]

Sedative/Hypnotics

Start here.