In this post, I link to and excerpt from Current guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review with comparative analysis [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. World J Gastroenterol. 2018 Aug 14; 24(30): 3361–3373.

The above article is cited by the 102 Articles in PubMed Central.

All that follows is from the above article.

Abstract

The current epidemic of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is reshaping the field of hepatology all around the world. The widespread diffusion of metabolic risk factors such as obesity, type2-diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia has led to a worldwide diffusion of NAFLD. In parallel to the increased availability of effective anti-viral agents, NAFLD is rapidly becoming the most common cause of chronic liver disease in Western Countries, and a similar trend is expected in Eastern Countries in the next years. This epidemic and its consequences have prompted experts from all over the word in identifying effective strategies for the diagnosis, management, and treatment of NAFLD. Different scientific societies from Europe, America, and Asia-Pacific regions have proposed guidelines based on the most recent evidence about NAFLD. These guidelines are consistent with the key elements in the management of NAFLD, but still, show significant difference about some critical points. We reviewed the current literature in English language to identify the most recent scientific guidelines about NAFLD with the aim to find and critically analyse the main differences. We distinguished guidelines from 5 different scientific societies whose reputation is worldwide recognised and who are representative of the clinical practice in different geographical regions. Differences were noted in: the definition of NAFLD, the opportunity of NAFLD screening in high-risk patients, the non-invasive test proposed for the diagnosis of NAFLD and the identification of NAFLD patients with advanced fibrosis, in the follow-up protocols and, finally, in the treatment strategy (especially in the proposed pharmacological management). These difference have been discussed in the light of the possible evolution of the scenario of NAFLD in the next years.

Keywords: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Metformin, Liver steatosis, Liver biopsy, Non-invasive diagnosis, Pioglitazone, Clinical guidelines

Core tip: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is becoming the most common cause of chronic liver disease. As such, an increasing number of scientific reports are investing this condition. To translate these evidence into clinical practice, international scientific societies have proposed guidelines for the management of NAFLD. In this review, we will critically analyse both the converging and diverging points in the current clinical guidelines of NAFLD, with a particular focus on the diagnostic and therapeutic aspects.

INTRODUCTION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) includes a spectrum of disorders ranging from the simple fatty liver to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, with increasing fibrosis leading to cirrhosis[1]. The prevalence of NAFLD is alarmingly growing worldwide in adult and children/adolescent populations, with a bidirectional association between NAFLD and metabolic syndrome[2]. Obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia are the most relevant metabolic conditions related to this spectrum of diseases[1,2].

Clinicians and researchers from several scientific Associations worldwide put significant efforts into increasing knowledge and developing high-quality International Guidelines to improve the management of NAFLD patients in clinical practice. Multidisciplinary panels of experts in different continents have performed systematic analysis and review of the literature on specified topics in the last years. These efforts have led to the creation and publication of various Guidelines.

This paper aims to review and compare the most recently published International Guidelines for the diagnosis and the management of NAFLD in adult populations, to critically evaluate similarities and discrepancies. In particular, we tried to analyse some critical questions and challenges for clinicians in real life.

OPEN QUESTIONS

Definition, classification, and diagnostic criteria of NAFLD

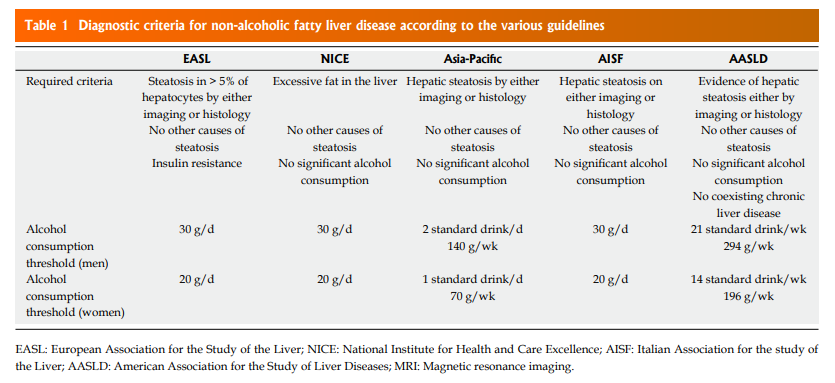

Definition and classification: A definition of NAFLD is reported in all Guidelines (Table (Table1).1). The characteristic points of NAFLD definition include (1) the evidence of excessive hepatic fat accumulation in the liver parenchyma (detected by imaging techniques or histology); (2) the absence of other secondary causes of hepatic fat. Out of them, to strictly define NAFLD patients a significant ongoing or recent alcohol consumption have to be excluded in all recommendation[3–8].

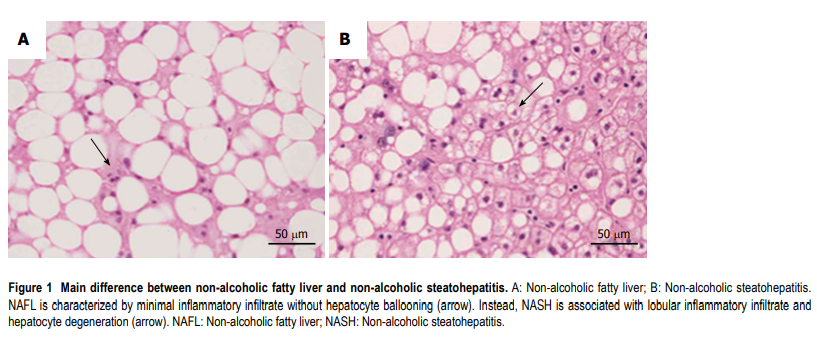

All recommendations identify some different clinical pathological entities, according to the progression of hepatic histological changes. Simple steatosis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are defined in all guidelines[3–8]. In detail simple steatosis, also called non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) includes all of the case characterized by steatosis with minimal or absent lobular inflammation. On the contrary, NASH is characterized by hepatocyte ballooning degeneration, diffused lobular inflammation and fibrosis (Figure (Figure1)

Additionally, EASL Asia-Pacific Guidelines and AISF position paper also underline the problem of NAFLD-related HCC, potentially occurring in patients with NAFLD but without cirrhosis[9,10].

Diagnostic criteria: The role of alcohol: The agreement between the different guidelines is not complete when defining the threshold dose of alcohol consumption. As shown in Table Table1,1, EASL[3], NICE, and AISF guidelines[3,4,7] consider as significant an alcohol consumption > 30 g/d in men and > 20 g/d in women. The AASLD guidance[8] indicate the reasonable threshold for significant alcohol consumption > 21 standard drink on average per week in men and > 14 in women. For Asia-Pacific Guidelines[5] a significant alcohol intake was considered > 7 standard alcoholic drinks/week (70 g ethanol) in women and > 14 (140 g) in men.

Who should be screened for NAFLD?

According to the screening programs adopted for other diseases, systematic screening has to be performed for significant health problem with available diagnostic facilities and accepted treatment. Also, there should be recognisable latent or early symptomatic stage, identifiable with sensitive tests. To adequately perform a screening program, the natural history of the disease should be understood, and the economic burden should be suitable.

The international guidelines partially diverge about this topic. This disagreement derives from essential considerations regarding natural history, special groups, diagnosis, and therapy: (1) NAFLD in a common cause of chronic liver disease in general population but cause severe liver disease in a small proportion of affected people[1]; (2)Type II diabetes patients have higher prevalence of NAFLD, NASH and advanced fibrosis[11–13]; (3) There is a current lack of effective drug treatment; (4) Liver biopsy is a procedure with related risks; (6) Few cost-effective analysis are available[14].

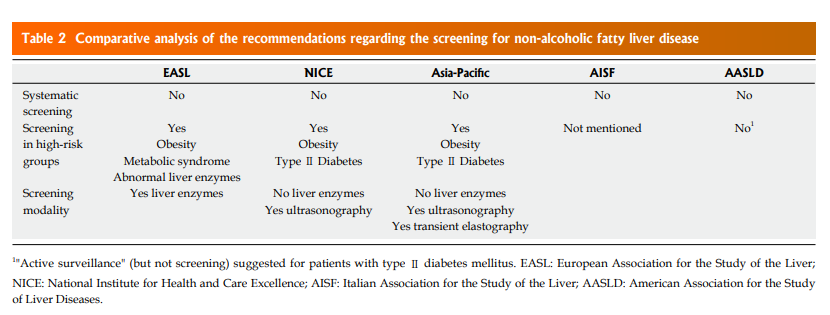

All these considerations imply a different approach to screening in NAFLD by the Scientific Societies. Only EASL, NICE Asia-Pacific Guidelines[3–5] recommend screening respectively in particular, “high-risk” groups (Table (Table2).2). On the contrary, AASLD guidelines emphasise that, to date, there is no evidence of cost-effectiveness to support a NAFLD screening in adults even if they have several metabolic risk factors, instead suggesting a concept of “vigilance” in these populations[8].

Which noninvasive test(s) should be used to diagnose NAFLD?

Worldwide guidelines agree that, whenever NAFLD is suspected, the initial diagnostic workup should include a noninvasive imaging examination to confirm the presence of steatosis and general liver biochemistry[3–8]. Non-invasive assessment should aim first of all to identify NAFLD among patients with metabolic risk factors, and then to monitor disease progression and treatment response, identifying patients with the worst prognosis[3].

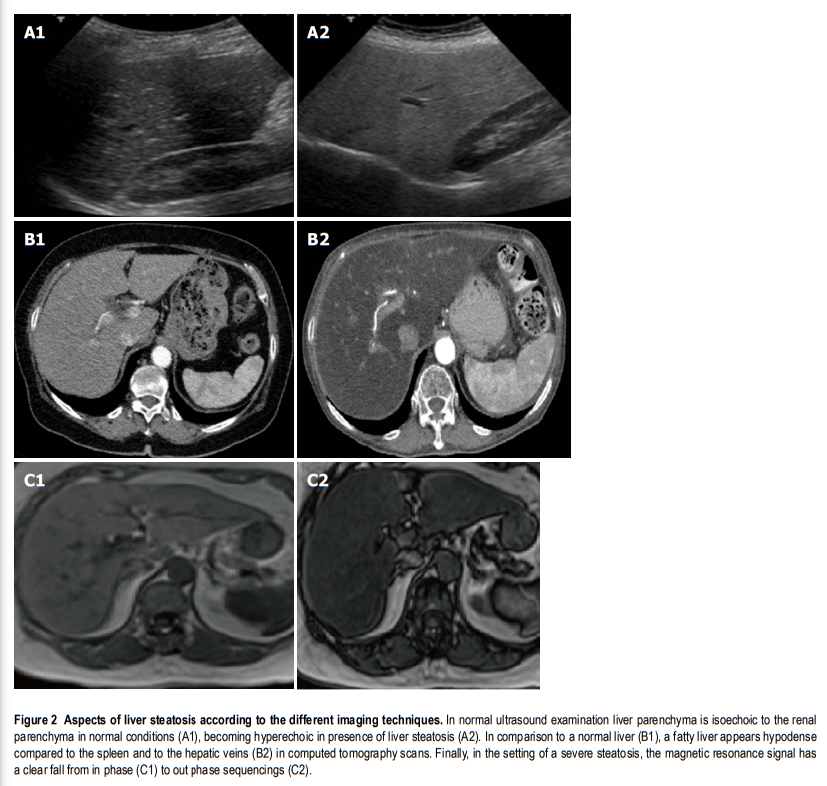

Imaging: There is a consensus for using abdominal ultrasound (US) as the first-line examination to identify liver steatosis in patients with increased liver blood exams or suspected NAFLD, in daily clinical practice (Figure (Figure2).2). The main advantages of US derive from its broad availability and low cost. However, its sensitivity among morbidly obese patients (BMI > 40 kg/m2) is low, and it may miss the diagnosis when the liver hepatic fat content is < 20%[15,16]. Despite these limitations, EASL and AISF underline how ultrasound can significantly assess moderate and severe steatosis, even if an observer dependency remains[15]. NICE guidelines propose to use liver ultrasound to detect hepatic steatosis for children with metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes and to retest it every three years if the first examination is negative[4].

On the other hand, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), either by proton density fat fraction (1H-MRS) or spectroscopy, remains the gold standard to assess and quantify hepatic steatosis, detecting the amount of liver fat as low as 5%-10%, its use in the clinical practice is still limited. In fact, despite its robust accuracy, its limited availability, high costs and a long time of execution, make the procedure not recommended in the daily clinical setting[17]. Asia-Pacific guidelines specify that 1H-MRS is the best option to quantify even moderate changes in liver fat content in clinical trials, considering its high sensitivity compared to histological-proven liver fat reversal. Similarly, EASL guidelines highlight its role, primarily as screening imaging examination for clinical trials and experimental studies[3].

Another imaging technique used to quantify liver fat content is the ultrasonography-based transient elastography (TE) using continuous attenuation parameter (CAP). This promising tool has shown a good sensitivity, measuring simultaneously liver stiffness, potentially evaluating NAFLD severity at the same setting[13]. However, despite its low cost and rapidity of execution, its role in the clinical practice has still to be defined. In fact, EASL guidelines specify that TE has never been compared with hepatic steatosis measured by 1H-MRS and there are limited data about its ability to discriminate different histological patterns[3]. On the other hand, Asia-Pacific guidelines propose CAP as a useful screening tool for NAFLD diagnosis, as well as for demonstrating improvement in hepatic steatosis after lifestyle intervention and body weight reduction[5].

Another imaging technique used to quantify liver fat content is the ultrasonography-based transient elastography (TE) using continuous attenuation parameter (CAP). This promising tool has shown a good sensitivity, measuring simultaneously liver stiffness, potentially evaluating NAFLD severity at the same setting[13]. However, despite its low cost and rapidity of execution, its role in the clinical practice has still to be defined. In fact, EASL guidelines specify that TE has never been compared with hepatic steatosis measured by 1H-MRS and there are limited data about its ability to discriminate different histological patterns[3]. On the other hand, Asia-Pacific guidelines propose CAP as a useful screening tool for NAFLD diagnosis, as well as for demonstrating improvement in hepatic steatosis after lifestyle intervention and body weight reduction[5].

Conventional liver biochemistry: Although NAFLD may present by standard laboratory liver tests, frequently a slight increase of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GammaGT) is observed. However, all the guidelines agree that normal levels of liver enzymes may not exclude NAFLD, being a not sensitive screening test[3–8].

Moreover, laboratory alterations may hide another cause of liver disease, in which steatosis is a coexisting condition. On the other hand, detection of abnormalities of laboratory exams (such as ferritin or autoantibodies) not always reflects the presence of another liver disease, but could be an epiphenomenon of NAFLD with no further clinical significance.

In particular, AASLD guidelines underline that elevate serum ferritin and low titers of autoimmune antibodies (especially antinuclear and anti-smooth muscle antibodies) are common features among NAFLD patients[18,19], and may not automatically indicate the presence of hemochromatosis or autoimmune liver disease[8].

Which is the role of diagnostic and prognostic scores?

Noninvasive predictor biomarkers and scores of steatosis and steatohepatitis: The current absence of a highly specific and sensitive noninvasive marker predicting inflammation and fibrosis is leading to a considerable interest in the identification of new markers of disease progression and to the development of clinical scores of disease severity.

To assess the presence of steatosis, EASL, Asia-Pacific, and Italian guidelines mention the Fatty Liver Index (FLI)[20] and the NAFLD liver fat score[21]. Both of these scores are easily calculated using common blood exams and simple clinical information. In detail, FLI is calculated from serum triglyceride, body mass index, waist circumference, and gamma-glutamyltransferase[20], while NAFLD liver fat score is calculated evaluating the presence/absence of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, fasting serum insulin, and aminotransferases[21].They have been validated in a cohort of severely obese patients and the general population, reliably predicting the presence of steatosis, but not its severity[22]. On the contrary, the AASLD guidelines underline that only inflammation and fibrosis dictate the prognosis of NAFLD patients and, consequently, highlight the lack of evidence of the usefulness of quantifying hepatic steatosis in the routine clinical setting. Instead, AASLD guidelines underline that the simultaneous presence of several metabolic diseases is the most potent predictor of hepatic inflammation and adverse outcome in patients with NAFLD.

The cytokeratin-18 fragment is currently the most studied biomarker to assess the presence of inflammation. Its circulating levels have been largely investigated as a signal of hepatocellular apoptotic activity and therefore as a characteristic feature of NASH[23]. Its role is addressed both by Asia-Pacific and EASL guidelines, which agree that the current evidence does not support its use in clinical practice and that more studies are needed[3,5]. In particular, Asia-Pacific guidelines highlight how increased levels of cytokeratin-18 have good predictive value for NASH vs normal livers but do not differentiate NASH vs simple steatosis[24,25]. On the other hand, EASL guidelines specify that has been demonstrated that cytokeratin-18 serum levels decrease parallel with histological improvement, but its predictive value is not better than ALT in identifying histological responders[26].

To conclude, guidelines agree that noninvasive tests for detecting NASH and distinguishing it from simple steatosis are not currently available and that liver biopsy remains necessary to detect hepatocyte ballooning and lobular inflammation[3–8].

Noninvasive assessment of advanced fibrosis: Liver fibrosis is considered the leading prognostic factor among patients with NAFLD because of its strong correlation with survival rate and liver-related outcomes[27]. Therefore, NAFLD patients with advanced fibrosis need a closer monitoring and a rigorous adherence to treatment. However, to date, no methods easily performed in daily clinical practice and with a high predictive value for differentiating grades of liver fibrosis have been identified.

Different tools have been investigated at this purpose, including noninvasive scores (NAFLD fibrosis score, Fibrosis 4 calculator, AST/ALT ratio index), serum biomarkers (ELF panel, Fibrometer, Fibrotest, Hepascore) and imaging techniques, such as transient elastography, magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) and shear wave elastography[28].

According to the NICE guideline, the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) blood test has shown the best cost-effectiveness in identifying patients with advanced fibrosis stages[29] and therefore should be offered to all patients with an incidental diagnosis of NAFLD[4]. On the other hand, EASL and Italian guidelines suggest the use of NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) and Fibrosis 4 calculator (FIB-4) as noninvasive scores to identify patients with different risk of advanced fibrosis[3,7]. These two scores have been validated in various ethnically NAFLD patients, predicting liver and cardiovascular-related mortality[30]. Moreover AASLD guidelines highlight that in a recent study both NFS and FIB-4 have shown the best predictive value for advanced fibrosis among histological proven NAFLD patients in comparison with other scores[28]. EASL guidelines underline that NFS has a stronger negative predictive value for advanced fibrosis than the corresponding positive predictive value[30]. Hence, it should be used for excluding the presence of advanced fibrosis better than stratifying NAFLD patients on different fibrosis stages[3].

Transient elastography has been recently approved by US Food and Drug Administration to investigate adult and pediatric patients with liver disease. Its cut-off value for advanced fibrosis for adults with NAFLD has been established to 9.9 KpA with 95% sensitivity and 77% specificity[31]. In particular, elastography score has been shown to have good diagnostic accuracy for the presence of clinically significant fibrosis, with an AUROC of 0.93 (95%CI: 0.89-0.096) for advanced fibrosis (≥ F3) and cirrhosis, and with a negative predictive value of 90% in ruling out cirrhosis when using a cut-off of 7.9 kPa.

American guidelines underline the vital role of magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) in identifying different degrees of fibrosis in patients with NAFLD, performing better than transient elastography for recognising intermediate stage of fibrosis, but showing a same predictive value for advanced fibrosis stages[34]. Therefore AASLD guidelines conclude that MRE and transient elastography are both useful tools for identifying NAFLD patients with advanced liver fibrosis.

Similarly, the AASLD guidelines consider NFS, FIB-4, transient elastography, and MRE as the first-line examination to detect patients with advanced fibrosis[8]. Differently from the EASL guidance, however, no diagnostic algorithms or follow up strategies are provided.

Similarly, the AASLD guidelines consider NFS, FIB-4, transient elastography, and MRE as the first-line examination to detect patients with advanced fibrosis[8]. Differently from the EASL guidance, however, no diagnostic algorithms or follow up strategies are provided.

The Asia-Pacific guidelines also agree that combined use of serum tests and imaging tools may offer more reliable information than using either method alone[6]. However, they do not specify which noninvasive test is best.

According to the NICE guidelines, every patient with an incidental finding of NAFLD should be screened for advanced fibrosis by ELF blood test. If negative, it should be repeated every three years for adults and two years for children. Moreover, children and young people with type 2 diabetes mellitus or metabolic syndrome, but without steatosis at ultrasound examination, should be reevaluated every three years[4].

Who should undergo liver biopsy?

To date, liver biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing NASH and staging liver fibrosis, despite several limitations such as sampling error, variability in interpretation by pathologists, high cost and patient discomfort[36]. The “NAFLD Activity Score” (NAS)[37] and the “Steatosis Activity Fibrosis” (SAF) scoring system[38] are recommended to assess disease activity[8].

Except for the NICE guidelines (which do not provide specific indications about which patients should undergo liver biopsy), all of the remaining guidelines substantially agree that confirmatory liver biopsy should not be performed in every NAFLD patients. Instead, it should be reserved for the following two situations: (1) Uncertain diagnosis; (2) suspect of NAFLD-related advanced liver disease.

The AASLD guidelines suggest to perform liver biopsy in patients with metabolic syndrome who are at increased risk of liver inflammation, or when NFS, FIB-4 or liver stiffness measured by transient elastography or MRE suggest the presence of advanced liver fibrosis. In that case, patients would benefit the most from diagnosis, obtaining crucial prognostic information[8].

Similarly, EASL and Italian guidelines recommend performing a liver biopsy when both serum and imaging noninvasive tools show a medium/high risk of advanced liver disease, with the aim to confirm the presence of advanced liver fibrosis. Furthermore, they underline that in selected NAFLD patients at high risk of disease progression, the repetition of liver biopsy should be considered case-by-case every five years[3,7]. On the other hand, the Asia-Pacific guidelines recommend biopsy only when a competing aetiology of chronic liver disease cannot be excluded just by laboratory exams and personal anamnesis, or results of noninvasive tests are inconclusive[5,6].

How to treat NAFLD?

Lifestyle changes: Lifestyle modification consisting of diet, exercise, and weight loss has been advocated to treat patients with NAFLD in all guidelines (Tables (Tables33 and and4).4). Indeed, weight loss has been reported as a keystone element in improving the histology features of NASH[39,40].

Post fig5 when server ready.