Here are excerpts from Mildly Elevated Liver Transaminase Levels: Causes and Evaluation [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Dec 1;96(11):709-715:

Abstract

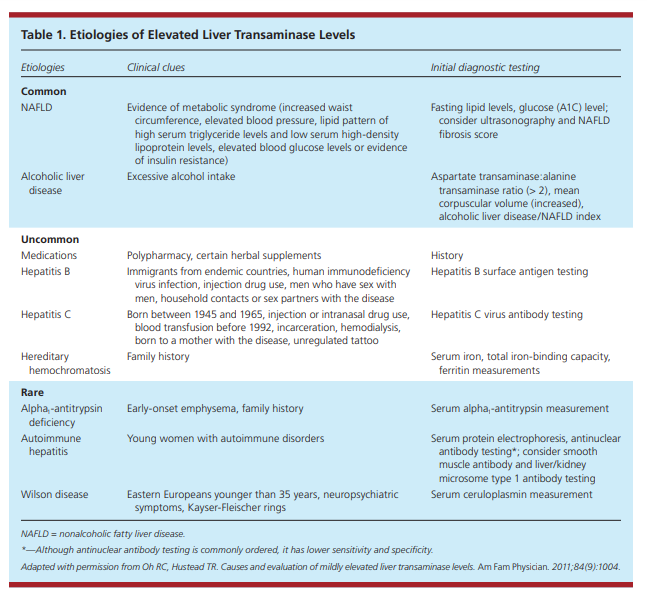

Mild, asymptomatic elevations (less than five times the upper limit of normal) of alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase levels are common in primary care. It is estimated that approximately 10% of the U.S. population has elevated transaminase levels. An approach based on the prevalence of diseases that cause asymptomatic transaminase elevations can help clinicians efficiently identify common and serious liver disease. The most common causes of elevated transaminase levels are nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and alcoholic liver disease. Uncommon causes include drug-induced liver injury, hepatitis B and C, and hereditary hemochromatosis. Rare causes include alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, autoimmune hepatitis, and Wilson disease. Extrahepatic sources, such as

thyroid disorders, celiac sprue, hemolysis, and muscle disorders, are also associated with mildly elevated transaminase levels. The initial evaluation should include an assessment for metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance (i.e.,

waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting lipid level, and fasting glucose or A1C level); a complete blood count

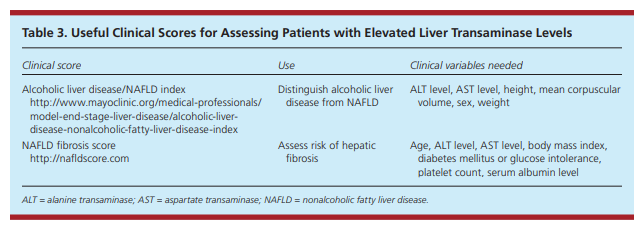

with platelets; measurement of serum albumin, iron, total iron-binding capacity, and ferritin; and hepatitis C antibody and hepatitis B surface antigen testing. The nonalcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score and the alcoholic liver disease/nonalcoholic fatty liver disease index can be helpful in the evaluation of mildly elevated transaminase levels. If testing for common causes is consistent with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and is otherwise unremarkable, a trial of lifestyle modification is appropriate. If the elevation persists, hepatic ultrasonography and further testing for uncommon causes should be considered. (Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(11):709-715. Copyright © 2017 American Academy of Family Physicians.)Mild, asymptomatic elevations of alanine transaminase

(ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels, defined as less than five times the upper limit of normal, are common in primary care. The prevalence of elevated transaminase levels is estimated to be approximately 10%, although less than 5% of these patients have a serious liver disease.1,2 Understanding the

epidemiology of each condition that causes asymptomatic elevated transaminase levels can guide the evaluation.3-6Causes of Elevated Liver Transaminase

LevelsHepatocellular damage releases ALT and AST. Elevations in ALT generally are more specific for liver injury, whereas elevations in AST can also be caused by extrahepatic

disorders, such as thyroid disorders, celiac sprue, hemolysis, and muscle disorders.7The AST:ALT ratio can suggest a specific disease or give insight into liver disease severity. In a study differentiating alcoholic liver disease from nonalcoholic liver disease, alcoholic liver disease was suggested with an AST:ALT ratio greater than 2 (mean AST:ALT values were 152:70; positive likelihood ratio [LR+] = 17, negative likelihood ratio [LR–] = 0.49). On the other hand, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was associated with a ratio of less than 1 (mean AST:ALT values were 66:91;

LR+ = 80, LR– = 0.2).8However, causes of mild, asymptomatic elevation of transaminase levels can generally be categorized as common, uncommon, and rare (Table 1).9

COMMON HEPATIC CAUSES

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

A systematic review found that NAFLD is the most common cause of asymptomatic elevation of transaminase levels (25% to 51% of patients with elevated ALT or AST, depending on

the study population).1,10 NAFLD is divided into two

subtypes. The first is nonalcoholic fatty liver, defined

as hepatic steatosis without inflammation. The second,

more severe subtype is nonalcoholic steatohepatitis,

which is characterized by hepatocyte injury with ballooning of cells, inflammation, and in severe cases, fibrosis.10

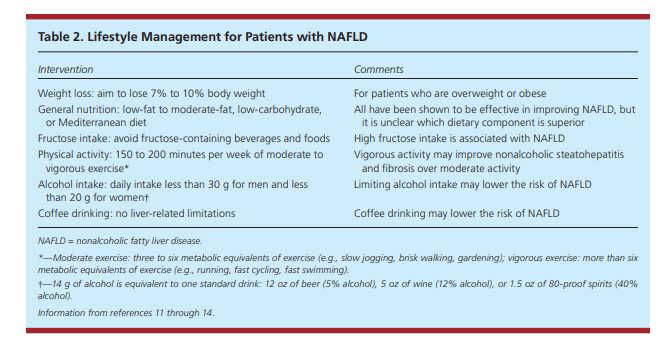

Nonalcoholic fatty liver is generally benign and treated

successfully with lifestyle modification (Table 211-14),

whereas patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis have

significant risk of progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

The prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is estimated at 3% to 5% of the adult population.10 Thus, the clinical challenge is to determine which patients with NAFLD are at risk of progression.

Ultrasonography* is the preferred first-line imaging modality for diagnosing hepatic steatosis,6,11,17 but it does not readily differentiate between nonalcoholic fatty liver and nonalcoholic

steatohepatitis.*See Diagnostic Accuracy and Reliability of Ultrasonography for the Detection of Fatty Liver: A Meta-Analysis 2011. Resource (4) below.

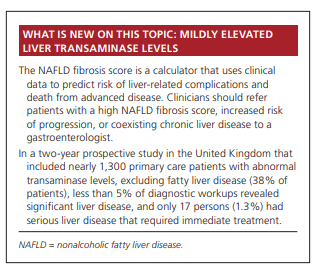

Given the variable progression of NAFLD, it is important to identify those at risk of advanced disease. The presence of liver fibrosis has been shown to be the best predictor of progression.18 Fibrosis is more common in patients older than 50 years.15 A number of clinical tests have been developed to help identify patients with fibrosis in lieu of a liver biopsy. The NAFLD fibrosis score (Table 3) uses clinical data to predict risk of liver-related complications and death from advanced disease.19

Patients with a high NAFLD fibrosis score, increased risk

of progression, or coexisting chronic liver disease should

be referred to a gastroenterologist.10Vibration-controlled transient elastography has emerged as a useful noninvasive modality to assess for hepatic fibrosis and may help determine which patients should undergo liver biopsy.

Alcoholic Liver Disease

Excessive alcohol intake is the primary cause of liver-related mortality in western countries.21 Alcoholic liver disease and NAFLD have significant overlap in disease spectrum and histopathology.22 If history does not clearly distinguish the two conditions, the alcoholic liver disease/NAFLD index (Table 3) [above] can be used. This index differentiates the conditions based on ALT level, AST level, height, mean corpuscular volume,

sex, and weight. It has an LR+ of 12 and an LR– of 0.07, and has been prospectively validated in several varied populations.22-24UNCOMMON HEPATIC CAUSES

start here

Resources:

(1) Mildly Elevated Liver Transaminase Levels: Causes and Evaluation [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Dec 1;96(11):709-715.

(2) A systematic review of the prevalence of mildly abnormal liver function tests and associated health outcomes[PubMed Abstract] [Full Text[Full Text PDF] . Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Jan;27(1):1-7. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000233.

(3) Guidelines on the management of abnormal liver blood tests [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Gut. 2018 Jan;67(1):6-19. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314924. Epub 2017 Nov 9.

(4) Diagnostic Accuracy and Reliability of Ultrasonography for the Detection of Fatty Liver: A Meta-Analysis [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Hepatology. 2011 Sep 2; 54(3): 1082–1090.

The above article has been cited by over 100 articles in PubMed Central.

.