In this post, I link to and excerpt from the Cribsiders‘ #28: Childhood Leukemia.

JUNE 30, 2021 By JUSTIN BERK

Lee N, Corty EW, Chui C, Berk J. “Childhood Leukemia”. The Cribsiders Pediatric Podcast. https:/www.thecribsiders.com/28 June 30, 2021

All that follows is from the above resource.

Summary

Is it growing pains, a bad infection, or could it be something more sinister? Join us to learn the ins and outs of childhood leukemia with Dr. Tanya Watt. On this episode we learn about the risk factors, early symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of children with various types of leukemia. Dr. Watt also teaches us about best practices for those difficult discussions with parents and children and what to look out for among adult survivors of childhood leukemia. Ready to jump on the rocketship of learning? Blast off!

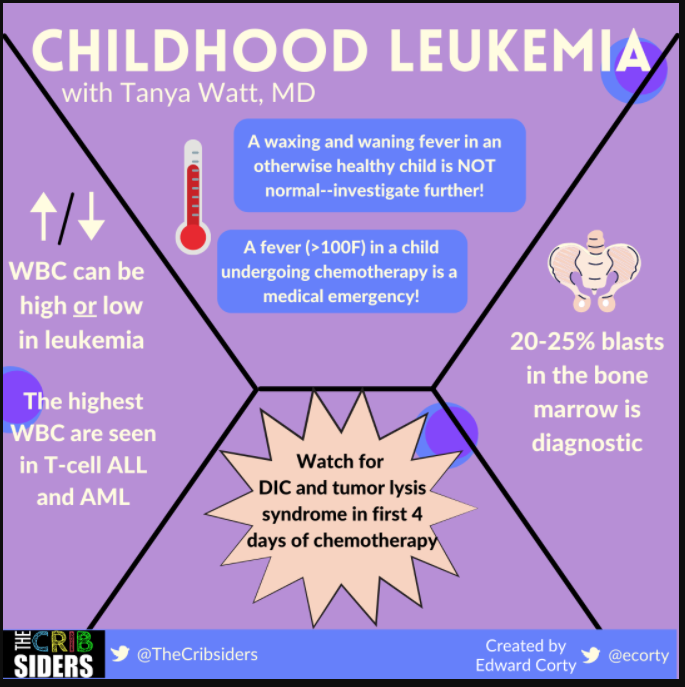

Childhood Leukemia Pearls

- A child with a fever that comes and goes for two weeks should raise an alarm bell

- Leukemia can present with either a high white count or a low white count

- The highest white counts tend to be found in T-cell ALL and AML

- In a child undergoing chemotherapy for leukemia, a fever (persistently over 100F) is a medical emergency

- Children are most at risk for tumor lysis syndrome and DIC during the first 4 days of chemotherapy treatment

- A child with leukemia can expect close to 30 lumbar punctures across their treatment from start to finish

- Try to get patients who are in remission plugged in with a “survivor clinic” to monitor long term conditions and complications

Childhood Leukemia Notes

Signs/symptoms that make you really start to think about cancer

- A child with two weeks of fever on and off is worrisome as viral conditions usually don’t last two weeks

- Families usually think of growing pains at first, but those should respond well to tylenol or ibuprofen

- Easy bruising is a little difficult but look for it in places where bruises don’t normally happen like the back or abdomen. Petechiae are also not normal.

Epidemiology

Predisposing factors

Usually, a child developing leukemia is bad luck, but there are some risk factors including Trisomy 21, which confers a 15 times increased risk of leukemia. Other conditions associated with an increased risk include Fanconi anemia, Bloom syndrome, Kleinfelter syndrome, and neurofibromatosis (AAP Pediatrics in Review).

Incidence

- Most common age is the 2-4 range but there is another peak in early adolescence

- Children under the age of 1 have a much worse prognosis

Workup

- Chest x-ray: to look for mediastinal mass

- Bone marrow biopsy: with sedation

- Tumor lysis labs: K, Phos, Ca, Uric Acid, LDH

- DIC panel: PT, PTT, INR, fibrinogen

- Lumbar puncture: looking for leukemia cells in the CSF (unless the child is in DIC, then do NOT do an LP)

- Testicular exam: look for unilateral swollen, firm testicle

Random lab pearls

- You tend to have more end organ damage at lower white counts with myeloid disease as compared with lymphoid disease. This is an important distinction because you may have to consider leukapheresis if there is end organ damage.

- If you’re going to start leukapheresis, you need to start chemo as well

- The highest white counts tend to be associated with T-cell ALL or AML

- Sometimes leukemias have low white cell counts–this is likely due to increased white count getting “stuck” in the bone marrow

Possible mimickers

Occasionally really bad infections will get a leukemoid reaction up to WBC of 25,000-30,000. In addition, juvenile idiopathic rheumatoid arthritis can share many signs and symptoms with leukemia (AAP Pediatrics in Review).

Diagnosis

- Somewhere between 20-25% blasts in the bone marrow is diagnostic for leukemia. In addition, a diagnosis can be made from peripheral blood in instances where the blasts are high enough. A bone marrow, however, is necessary to definitely diagnose leukemia (AAP Pediatrics in Review).

- ⅔ of leukemia is lymphoid: ⅔ of those are B-cell ALL, ⅓ are T-cell ALL

- Blasts tend to be smaller, scant cytoplasm

- ⅓ is myeloid

- Blasts tend to be bigger, more granules in cytoplasm

Complications

Infection

- Children with ALL are immunosuppressed for 3 to 3.5 years!

- Fever becomes a medical emergency (persistently over 100F)

- Severe neutropenia is considered ANC < 500

- Patients with febrile, severe neutropenia should receive empiric IV antibiotics

Tumor lysis syndrome

- This can occur within 24-72 hours of starting chemo

- All of the intracellular components get sent into the bloodstream

- Treatment is preventative with IV IVG and allopurinol/rasburicase

- The most important thing during this time is hydrating the kids a lot to avoid kidney injury, which can be due to:

- Uric acid crystals (affected by allopurinol and rasburicase)

- Calcium phosphate crystals (cannot be affected by medicines; requires hydration)

- Burkitt leukemia has highest incidence, then T-cell leukemia, then B-cell leukemia

- AML tends to cause more DIC and less tumor lysis syndrome

DIC

- This occurs within first 3-4 days of chemo

- Granules within myeloid blasts lyse and lead to DIC

- Most classic in APML (M3AML)

- Diagnosis based on low fibrinogen levels (< 100); treatment is transfusion of cryoprecipitate

Other complications to watch for

- Pancreatitis

- Blood clots

- Chemotherapy and medication-related side effects (hypertension, hyperglycemia, peripheral neuropathy)

Treatment

- B-cell and T-cell ALL: outpatient chemotherapy (+/- cranial radiation depending on CNS disease) for 2.5-3 years

- Throughout treatment, a child can expect to have between 25 and 30 lumbar punctures! Manage expectations about this unfortunate, but necessary test.

Prognosis

- B-cell ALL is the best: 85-90% 5-year event free survival

- T-cell ALL: 70-80% 5-year event free survival (very difficult to treat after relapse)

- AML: 60% 5-year event free survival

- There are not many modifiable risk factors

- Survivor clinics are a great resource to think about long-term issues (e.g. doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy)

Talking to Parents

- Tell the parents that you know they are thinking their child is going to die but that you hope the treatment is successful and this is just a bad memory.

- Let the parents know that you are going to be honest with them. You will let them know when you are worried.

- Never promise anything (even if it is the “best” type of cancer to have)–continue to use “I hope” or “that is my expectation.”

Talking to Children

- Communicate to children that it’s good that we know what is causing them to be sick and that they will have some good days and bad days, but that we will work together to make this go away as soon as possible.

CITATIONS

- Joel A. Kaplan. Leukemia in Children. Pediatrics in Review. July 2019, 40 (7) 319-331; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.2018-0192