In this post, I link to and excerpt from Transient synovitis of the hip: which investigations are truly useful? [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Download Full Text PDF]. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015 Aug 21;145:w14176. doi: 10.4414/smw.2015.14176. eCollection 2015.

Here are excerpts:

What Follows is From Discussion

This study confirms that a vast majority of children with

acute hip pain or limp suffer from TSH, a benign and self-limiting condition. Children with suspicion of TSH may

therefore be treated on an outpatient basis, provided that

severe hip disorders, such as septic arthritis of the hip or

acute SCFE, have been ruled out.[Over investigation leads to unnecesary expense and patient and parental disgress.] Thus, initial investigations should, in our opinion, include WBC count, CRP and ESR, and X-rays

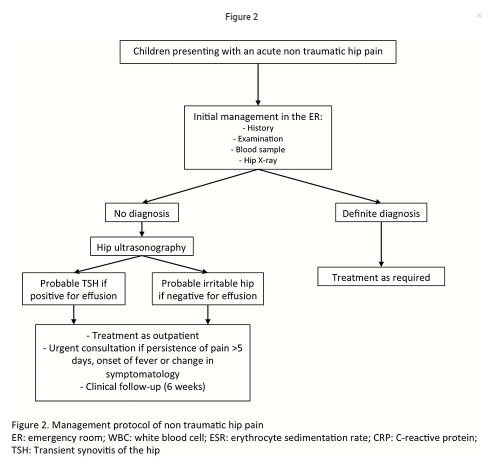

imaging of the hip (fig. 2).

In the absence of a definite diagnosis, we suggest hip ultrasonography should be performed.

In the presence of hip effusion without suspicion of septic arthritis*, patients could be considered to have a probable transient synovitis of the hip.

*Link is to Septic Arthritis BY DR SEAN M. FOX · AUGUST 28, 2015 of Pediatric EM Morsels.

In the absence of hip effusion, children may be considered to have a so-called irritable hip.

However, other diagnoses, such as osteomyelitis, should be kept in mind and excluded in the case of persistence of symptoms.

In both situations, children may be treated on an outpatient basis and parents must be told to seek medical care urgently in the event of any change in symptomatology, onset of fever, or persistence of pain.

Children should be referred to their paediatrician or paediatric orthopaedist for a check-up 6 weeks after the initial workup only in the case of persistence of symptoms.

Also, radiographic views are unnecessary during followup for TSH in the asymptomatic child.

Finally, screening for rheumatological diseases, acute rheumatic fever, poststreptococcal reactive arthritis, or Lyme disease is not justified at the time of presentation at the emergency room

START HERE ABOVE

Summary

The medical records of children admitted at our children’s hospital for nontraumatic hip pain between 1999 and 2007 were retrospectively reviewed. During the study period, all children without a definite diagnosis after routine investigations in the emergency department were admitted and a specific work-up including antinuclear antibodies titre, rheumatoid factor, antistreptolysin O titre, Lyme disease serology and hip ultrasonography were obtained.

Patients were diagnosed with transient synovitis of the hip if an ultrasound-confirmed hip effusion was present at time of admission, complete resolution of symptoms occurred without any specific treatment, and no other pathology of the hip was identified during followup.

A total of 417 cases without definite diagnosis were admitted and were submitted to a specific work-up. Transient synovitis of the hip was subsequently diagnosed in 383 patients, septic arthritis in 1 patient, and Lyme arthritis in 1 patient. Thirty-two patients remained without diagnosis. No rheumatological condition was found.

Our results suggest that most investigations performed during the initial work-up in patients suspected transient synovitis of the hip are unnecessary and should routinely include only white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and hip radiography and ultrasonography. No further investigations are necessary during follow-up for transient synovitis of the hip in asymptomatic children.

Introduction

Children presenting with acute nontraumatic hip pathology

can display a wide variety of nonspecific symptoms, such as a limp or abnormal gait, pain, refusal to bear weight or decreased movement of the involved joint.These complaints represent a diagnostic problem for paediatricians and emergency physicians, not only because of the broadness of these complaints but also because the differential diagnosis varies from quite harmless conditions such as transient synovitis of the hip to more severe problems such as Legg-Calvé-Perthes’ disease (LCP), slipped capital

femoral epiphysis (SCFE) and life-threatening conditions

such as septic arthritis of the hip [1] .The most common cause of hip pain and limp in children is transient synovitis of the hip (TSH) [1, 2]. Commonly, the age of presentation is between 4 to 10 years, and the boy to girl ratio is 2:1 [2,3]. Symptom resolution without any specific treatment in

a matter of days is an essential feature of diagnosis [2, 3].However, the symptoms of TSH are nonspecific and may

be present in many other potentially serious hip conditions.Because of the potential risk of missing a serious condition in this situation, acute nontraumatic limping children are promptly referred and often over-investigated [6,7].

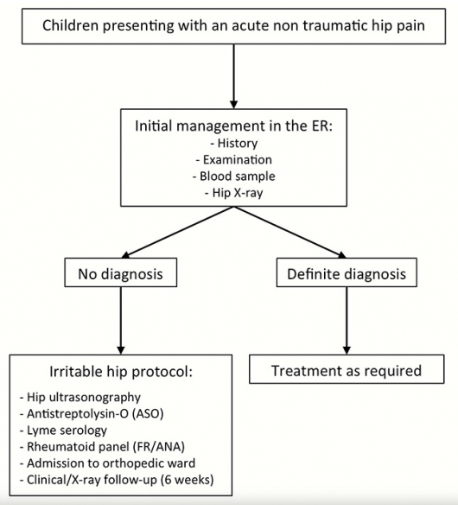

In our institution, a strict investigation protocol for children presenting with an acutely irritable hip in the emergency room was applied systematically between 1999 and 2007 (fig. 1).

The primary aim of this study was to assess whether the investigation model used at our hospital could exclude all hip

pathologies, in the case of an inconclusive initial survey at

the emergency department.Secondly, it was intended to assess which investigations were truly necessary in this setting.

Finally, we wanted to elaborate a comprehensive and

adapted protocol for the management of a child presenting

an acutely irritable hip.Results

Between January 1999 and April 2007, 440 patients were

admitted at our paediatric orthopaedic ward with a chief

complaint of nontraumatic hip pain or a limp.Among these patients, 74 were given a definite diagnosis based on clinical, laboratory and radiological work-up at time of presentation at the emergency room. There were 2 cases of septic arthritis, 46 of Perthes’ disease, 2 of juvenile arthritis, 20

of SCFE, 1 Kawasaki’s disease, 1 myositis ossificans, 1 fibrous dysplasia of the proximal femur, and 1 blood effusion of the hip due to haemophilia.[Other causes of limp* include Benign Acute Childhood Myositis, Rhabdomyolysis (Be sure and review the thoughtful readers’ comments in this post), Toddler’s Fracture, Osteomyelitis, Osteosarcoma, Osgood Schlatter’s Disease, Kohler’s Disease: Avascular Necrosis of the Navicular Bone]

*All of the above are direct links to posts from Pediatric EM Morsels.

The remaining 366 patients with nondiagnostic initial work-ups were managed under the specific protocol as described in the methods section and fulfilled the inclusion criteria for this study.

Among these patients, 51 (14%) had another episode of hip

pain requiring readmission to the hospital during the study

period. In total, 417 hospitalisation episodes for hip pain

without a definite diagnosis at the emergency room were

collected.Among this group, the diagnosis of TSH was subsequently confirmed in 383 (91.8%) cases.

After admission on the ward, one patient presented clinical and biological parameters (CRP of 51 mg/l and WBC count of 24.0 x

103/mm3) compatible with septic arthritis, and was treated

accordingly despite negative hip joint aspiration.One patient had Lyme arthritis diagnosed on positive Lyme’s serology, and the remaining 32 patients had a hip pain or limp

of unknown origin defined as irritable hips of unknown origin with a negative ultrasound for hip effusion (table 1).Among these 32 cases of irritable hip of unknown origin,

full recovery was observed at follow-up. Demographic data

of patients who underwent the specific protocol are shown

in table 1.

Clinical evaluation

Among the 383 patients with transient synovitis of the hip,

192 (51%) had symptoms for less than 24 hours prior to admission. When symptoms were present for more than 24

hours, mean symptom duration was 2.1 days (range 1–21

days) before medical attention was sought.Among patients (417) who underwent the specific “irritable hip protocol”, limping was present in 392 cases (94%), and 69 (16.5%) were absolutely unable to bear weight. In 23 (5%) cases,

no information was found concerning the weight-bearing

status.Only 5 (1.2%) patients presented an oral temperature greater than 38.5 °C at initial presentation. One hundred and seventy (40%) patients had an upper respiratory infection within 2 weeks preceding symptom onset.

Laboratory findings

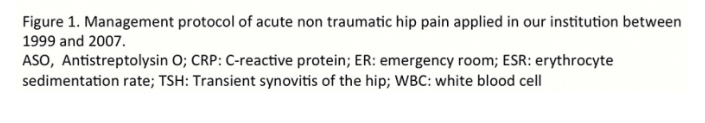

WBC count greater than >12.0 x 103 /mm3 was present in 47

(11.3%) children.Seventy-two patients had a CRP greater than 10 mg/dl with a median value of 15 ± 21.9 mg/ dl (5‒86). CRP was lower than 10 mg/dl in 345 patients (83%).

ESR was greater than 40 mm/h in 8 (2.4%) patients (table 2).

ASO titres were tested in 403 patients and were

above 200 U/ml in 87 (22%) cases. When abnormal, the median value was 400 U/ml, ranging from 300 to 800 U/ml (table 2).Lyme serology testing was performed in 323 patients and results were normal for all patients but one.

Rheumatological panel

ANA titres were assessed in 402 patients and were negative

in 341 cases (86%). Among the positive results, ANA titres

were higher than 1:80 in 25 cases (6%).Rheumatoid factor was tested in 388 patients and was positive in 60 (15%) cases; rheumatoid factor was above 6 U/ml in 60 (15%) patients (table 3). Among children with abnormal results

from the rheumatological panel, 38 underwent ophthalmological examination in order to rule out uveitis and all were normal.Radiological investigations

Indirect signs of effusion were seen in 82 (19.6%) children

on the standard pelvic radiographs, while no osseous abnormalities were noted.A hip ultrasound was performed in all patients.

Hip effusion was observed in 385 (92.3%) cases with a mean value of 6.7 mm (range 2–19 mm).

Clinical and radiological follow-up

Four hundred and two patients (96.4%) were seen for a clinical and radiological follow-up 6 weeks after hospital discharge and 15 were lost to follow-up.

Three hundred and ninety six children were asymptomatic and had a normal hip X-ray.

One patient had persistent pain despite a normal radiological aspect of the hip at 6 weeks follow-up. He required further follow-up, and hip X-rays at 12 weeks showed early signs of LCP disease.

Five patients had an asymmetrical aspect of the femoral

head on hip X-rays and required additional follow-up despite entire resolution of clinical symptoms. Eventually, all these patients had a complete and spontaneous resolution of radiographic anomalies.Consistently with current literature, our results show that

radiographs of the hip are often unremarkable in patients

with TSH and may show only indirect signs of effusion [14,

15]. The main reason for radiographic evaluation is to rule

out osseous lesions such as LCP disease, acute or chronic SCFE, or bone tumours, and should be obtained early in the diagnostic workup.Nevertheless, it is important to note that these hip disorders do not present with a similar history and clinical findings to TSH. Children with TSH have a complete resolution of symptoms in a week or less, even if residual symptoms may occasionally persist 7 to 10 days after the initial presentation [2, 16].

When compared with patients with TSH, patients with Perthe’s disease have a considerably longer duration of hip pain [17]. Analogously, children with chronic SCFE usually present with a history of limping for several weeks and poorly localised pain in

the hip, groin, thigh, or knee. Moreover, these latter children are often older than those with TSH.Ultrasound of the hip may help to confirm or exclude hip

effusion in children with suspicion of transient synovitis or septic arthritis [14, 18, 19]. However care must be taken not to misinterpret false-negative studies performed too early in the course of septic arthritis [20].Moreover, ultrasound is not discriminative in differentiating septic arthritis and TSH and should not be considered a safe diagnostic tool to confirm or exclude hip septic arthritis in

children [21, 22].In the present study, a hip ultrasound was performed in all children presenting with suspicion of TSH. A hip effusion was present in 92% of cases. All negative ultrasound cases were treated as TSH and had a 6-week follow-up. All had complete resolution of symptoms and no diagnostic entity could explain their initial clinical presentation