In this post I link to and excerpt from Unintentional Weight Loss in Older Adults [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Am Fam Physician. 2014 May 1;89(9):718-722.

Here are excerpts:

Abstract:

Unintentional weight loss in persons older than 65 years is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. The

most common etiologies are malignancy, nonmalignant gastrointestinal disease, and psychiatric conditions. Overall, nonmalignant diseases are more common causes of unintentional weight loss in this population than malignancy.

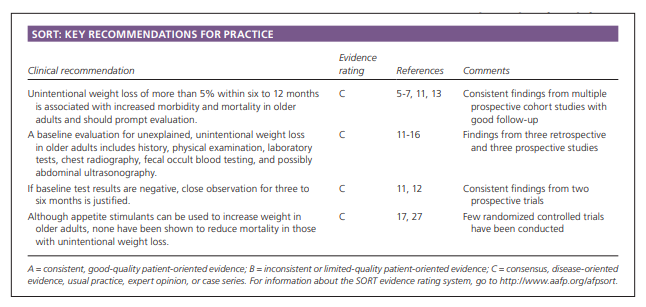

Medication use and polypharmacy can interfere with taste or cause nausea and should not be overlooked. Social factors may contribute to unintentional weight loss. A readily identifiable cause is not found in 16% to 28% of cases. Recommended tests include a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, thyroid function tests, C-reactive protein levels, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, glucose measurement, lactate dehydrogenase measurement, and urinalysis. Chest radiography and fecal occult blood testing should be performed. Abdominal ultrasonography may also be considered. When baseline evaluation is unremarkable, a three- to six-month observation period is justified. Treatment focuses on the underlying cause. Nutritional supplements and flavor enhancers, and dietary modification that takes into account patient preferences and chewing or swallowing disabilities may be considered. Appetite stimulants may increase weight but have serious adverse effects and no evidence of decreased mortality.[Introduction]

Unintentional weight loss (i.e., more than a 5% reduction in body weight within six to 12

months) occurs in 15% to 20% of older adults and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.1This article focuses on the evaluation, diagnosis, and potential treatments of unintentional weight loss in patients older than 65 years.

Etiology

The pathophysiology of unintentional weight loss is poorly understood.

Body composition changes with age. Lean body mass begins to decrease up to 0.7 lb (0.3 kg) per year in the third decade. This loss is offset by gains in fat mass that continue until 65 to 70 years of age. Total body weight usually peaks at 60 years of age with small decreases of 0.2 to 0.4 lb (0.1 to 0.2 kg)

per year after 70 years of age. Therefore, substantial weight changes should not be attributed to normal anorexia of aging.10Multiple studies, prospective and retrospective and in inpatient and outpatient settings, have demonstrated that the most common etiologies are malignancy (19% to 36%), nonmalignant gastrointestinal disease (9% to 19%), and psychiatric conditions such as depression and dementia (9% to 24%). Overall, nonmalignant diseases are more common than malignancy.1,11-16 Etiologies are further delineated in Table 1. 11-16

Medication adverse effects (Table 2 1,17,18) are common but often overlooked causative factors.17 Polypharmacy has been shown to interfere with taste and can cause anorexia.19 In addition, a variety of social factors are associated with unintentional weight loss and include poverty, alcoholism, isolation, financial constraints, and other barriers to obtaining food (e.g., impairment in activities of daily living, lack of assistance in grocery shopping or preparing meals).1

In 16% to 28% of patients, no readily identifiable cause for unintentional weight loss is determined.11 16

History and Physical Examination

If there is a concern about cognitive impairment, a caregiver or family member can provide corroborating information. The history should focus on the amount of weight lost and the time frame in which the weight loss occurred.

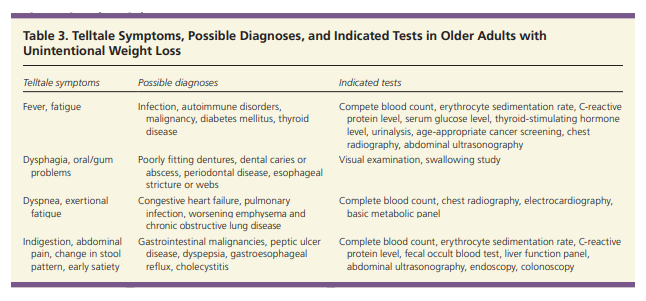

A review of systems to detect acute illness or worsening chronic conditions is important and

should pay particular attention to cardiovascular, respiratory, and gastrointestinal symptoms (Table 3).

The history should also identify prescription and over-the-counter medications and herbal supplements that may be affecting appetite or contributing to weight loss.

A social history focusing on alcohol and tobacco use and the patient’s living situation may elicit further useful information.

The Mini Nutritional Assessment is a validated tool

to help measure nutritional risk.22 The tool involves anthropometric measurements and general, dietary, and subjective assessments. Scoring allows categorization of older adults as well nourished (normal), at risk, or malnourished.22The Nutritional Health Checklist (Table 4) is a

simpler tool for assessing nutritional status that was developed for the Nutrition Screening Initiative.23

Assessment for depression and dementia is also vital because both have been shown to contribute to unintentional weight loss in older adults.1

The two question Patient Health Questionnaire (available at https://www.aafp.org/afp/2008/0715/p244.html) and the Geriatric Depression

Scale (available at https://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/1115/

p1149.html) are validated screening tools for depression in older adults.24,2The Mini-Cognitive Assessment Instrument (Mini-Cog is the preferred screening tool for dementia because of its ease of use.26

My own preferred tool for screening for dementia and mild cognitive impairment is the The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA.

The physical examination can aid in evaluating concerns prompted by history findings. Body weight without shoes should be assessed on a clinic scale. Evaluation of the oral cavity and dentition may indicate difficulty with chewing or swallowing. Heart, lung, gastrointestinal, and neurologic examinations evaluate for illnesses contributing to or causing weight loss.

Diagnostic Studies

Baseline investigations include laboratory studies and imaging. Recommended laboratory tests include complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, thyroid function tests, C-reactive protein levels, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, glucose measurement, lactate dehydrogenase measurement, and urinalysis.1

Chest radiography and fecal occult blood testing should also be performed. Abdominal ultrasonography may be considered.1A prospective study evaluated 101 patients (inpatient and outpatient) with an average age of 64 years and unintentional weight loss of at least 5% within six to 12 months.12

After baseline evaluation, the etiology of unintentional weight loss was established in 73 patients (72%). Organic disease was identified in 57

patients, and 16 patients had a psychiatric diagnosis.More importantly, all of the 22 patients with malignant disease had abnormal results in the baseline assessment. Tests with the highest yield (i.e., typically abnormal in the setting of organic disease) were C-reactive protein, hemoglobin, lactate dehydrogenase, and albumin measurements.

None of the 25 patients with negative findings on baseline evaluation had a malignancy on additional workup, such as computed tomography, endoscopy, colonoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging, or radionuclide examinations.

Therefore, the authors concluded that if baseline test

results are normal, further workup is not necessary, and close observation for three to six months is justified.11,12Treatment

Treatment should focus on the underlying cause.