Note to myself and my readers: I only post excerpts from articles because doing so helps me remember the important points [spaced repetition]. Readers should download the complete article [links below] and review that.

In this post I link to and excerpt from Section 4 Patients with new onset of heart failure or reduced left ventricular function from 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes: The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. European Heart Journal, Volume 41, Issue 3, 14 January 2020, Pages 407–477.

Here are the links to the above guidelines:

Article Contents

All that follows is the from the above

4 Patients with new onset of heart failure or reduced left ventricular function

CAD is the most common cause of HF in Europe, and most of the trial evidence supporting management recommendations is based on research conducted in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy. The pathophysiology results in systolic dysfunction due to myocardial injury and ischaemia, and most patients with symptomatic HF have reduced ejection fraction (<40%), although patients with CCS may also have symptomatic HF and a preserved ejection fraction (≥50%). Patients with symptomatic HF should be managed clinically according to the 2016 ESC heart failure Guidelines.*340

*2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)

Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML]. Eur Heart J. 2016 Jul 14;37(27):2129-2200.

History should include the assessment of symptoms suggestive of HF, especially exercise intolerance and dyspnoea on exertion. All major past events related to CAD including MI and revascularization procedures are recorded, as well as all major cardiovascular comorbidity requiring treatment such as AF, hypertension, or valvular dysfunction, and non-cardiovascular comorbidity such as CKD, diabetes, anaemia, or cancer. Current medical therapy, adherence, and tolerance should be reviewed.

Physical examination should assess the nutritional status of patients, and estimate biological age and cognitive ability. Recorded physical signs include heart rate, heart rhythm, supine BP, murmurs suggestive of aortic stenosis or mitral insufficiency, signs of pulmonary congestion with basal rales or pleural effusion, signs of systemic congestion with dependant oedema, hepatomegaly, and elevated jugular venous pressure.

A routine ECG provides information on heart rate and rhythm, extrasystole, signs of ischaemia, pathological Q waves, hypertrophy, conduction abnormalities, and bundle branch block.

Imaging should include an echocardiographic examination with Doppler to evaluate evidence of ischaemic cardiomyopathy with HF with reduced ejection fraction, HF with mid-range ejection fraction, or HF with preserved ejection fraction, focal/diffuse LV or right ventricular systolic dysfunction, evidence of diastolic dysfunction, hypertrophy, chamber volumes, valvular function, and evidence of pulmonary hypertension. Chest X-ray can detect signs of pulmonary congestion, interstitial oedema, infiltration, or pleural effusion. If not known, coronary angiography (or coronary CTA) should be performed to establish the presence and extent of CAD, and evaluate the potential for revascularization.52,53

Laboratory investigations should measure natriuretic peptide levels to rule-out the diagnosis of suspected HF. When present, the severity of HF can be assessed.25,49 Renal function along with serum electrolytes should be measured routinely to detect the development of renal insufficiency, hyponatraemia, or hyperkalaemia, especially at the initiation and during up-titration of pharmacological therapy.

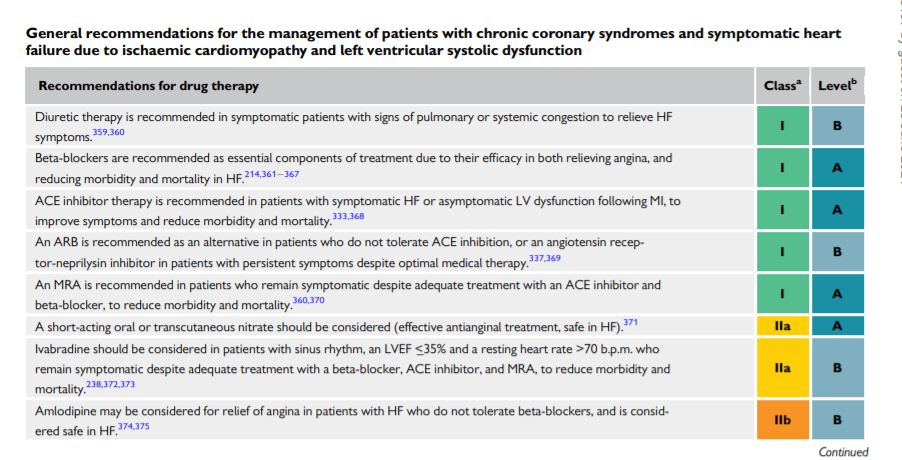

The management of patients with symptomatic HF requires adequate diuretic therapy, preferably with a loop diuretic, to relieve signs and symptoms of pulmonary and systemic congestion. Inhibitors of both the RAS system (ACE inhibitors, ARBs, angiotensin receptor−neprilysin inhibitor) and the adrenergic nervous system (beta-blockers) are indicated in all symptomatic patients with HF.340 In patients with persistent symptoms, an MRA is also indicated. Up-titration of these drugs should be gradual to avoid symptomatic systolic hypotension, renal insufficiency, or hyperkalaemia.

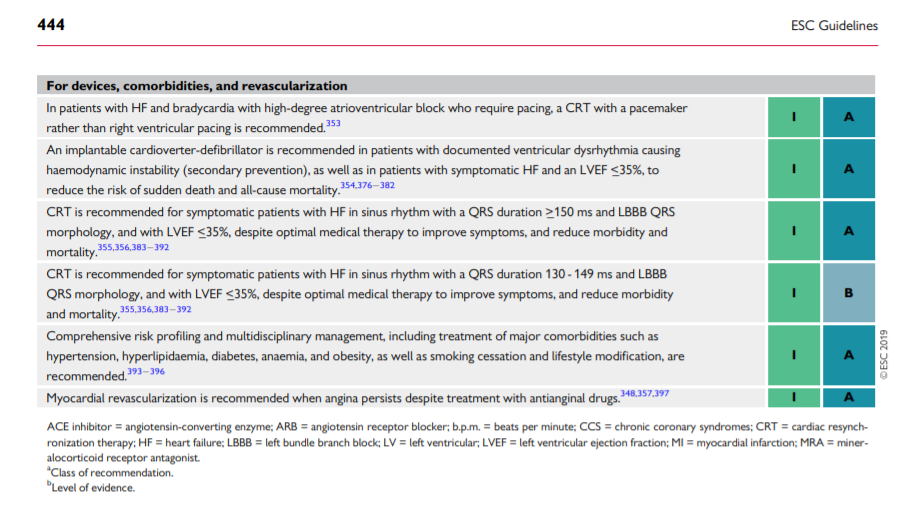

Patients who remain symptomatic, with LV systolic dysfunction and evidence of ventricular dysrhythmia or bundle branch block, may be eligible for a device [cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT)/implantable cardioverter-defibrillator]. Such devices may provide symptomatic relief, reduce morbidity, and improve survival.353–356 Patients with HF may decompensate rapidly following the onset of atrial or ventricular dysrhythmia, and should be treated according to current Guidelines. Patients with HF, and haemodynamically significant aortic stenosis or mitral insufficiency, may require percutaneous or surgical intervention.

Myocardial revascularization should be considered in eligible patients with HF based on their symptoms, coronary anatomy, and risk profile. Successful revascularization in patients with HF due to ischaemic cardiomyopathy may improve LV dysfunction and prognosis by reducing ischaemia to viable, hibernating myocardium. If available, cooperation with a multidisciplinary HF team is strongly advised.348,357,358