The antiphospholipid syndrome, the lupus anticoagulant, and antiphospholipid antibodies are terms I’ve heard since medical school and never fully understood them.

So then I listened to Dr. Farkas’ podcast on Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome (CAPS). And now I had something new I didn’t fully understand and it was something that I had never heard about.

So in this post, I’ve made study notes of his post and other resources to see if I could better understand antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome.

In this post I listened to and reviewed Dr Josh Farkas’ Internet Book of Critical Care chapter “Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome (CAPS)” [Link To Podcast] [Link To Show Notes].Dr. Farkas introduces the podcast:

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is a truly rare cause of multi-organ failure. It is usually not considered as a diagnostic possibility, leading it to be mis-diagnosed as septic or cardiogenic shock. Awareness of this condition and various red flags suggesting its presence might facilitate earlier diagnosis and therapy.

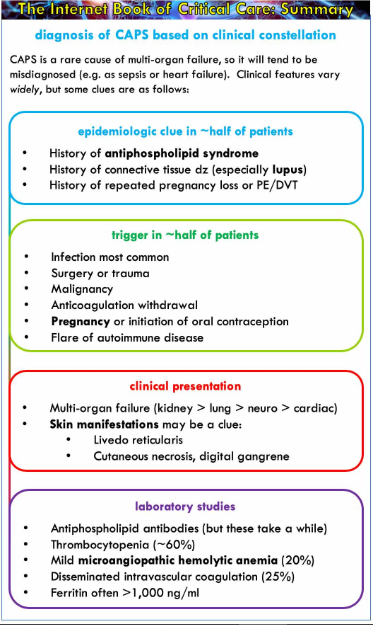

And here is Dr. Farkas’ outstanding summary graphic of the topic:

So what follows is my notes as I attempt to better understand the antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) and the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS).

What follows is from Medscape Anticardiolipin Antibody Background:

Background

Description

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by recurrent thrombosis and pregnancy morbidity in the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (APLA). APS is diagnosed when at least one requirement from both clinical and laboratory criteria are met.

Clinical criteria include the following:

Vascular thrombotic episodes in any tissue or organ

Pregnancy loss (≥1 unexplained loss of a normal fetus beyond the 10th gestational week, ≥1 premature birth before the 34th gestational week due to eclampsia or placental insufficiency, or ≥3 spontaneous abortions before the 10th gestational week)

Laboratory criteria include the following:

Lupus anticoagulant (LA) present in serum

Anticardiolipin (aCL) antibody of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and/or immunoglobulin M (IgM) isotype present in serum (>40 GPL or MPL units, or above the 99th percentile)

Anti–beta2 glycoprotein-I (b2-GPI) antibody of IgG and/or IgM isotype (in titer above the 99th percentile) in serum [4]

Although not included in the diagnostic criteria, other clinical symptoms, such as livedo reticularis, nephropathy, thrombocytopenia, cardiac valvular disease, and neurological symptoms are commonly associated comorbidities. [5]

An anionic side of the phospholipids that constitutes the cell membrane normally faces the cytoplasm. In the setting of initial injury, the anionic surface is exposed to the exterior. aCL binds to the anionic phospholipid on the platelet membrane and to the b2-GPI free flowing in the serum. Deposition of this aCL immune complex causes additional exposure of anionic phospholipids and platelet activation by unidentified signal transducing mechanisms. This cascade eventually leads to the formation of thrombosis. APLA refers to other prothrombotic antibodies that behave similarly to aCL. LA and anti–b2-GPI are among the APLAs. [6]

Indications/Applications

aCL testing is performed as part of the workup of excessive clotting episodes, along with LA and anti–b2-GPI antibody tests.

In addition, aCL testing is indicated in certain clinical settings.

aCL testing is warranted in young patients with unexplained arterial or venous thrombosis who lack evidence of atherosclerosis or emboli or develop thrombosis at unusual sites. [6] History of pregnancy loss also justifies aCL testing.

What follows is from Antiphospholipid Syndrome (Antiphospholipid Antibody Syndrome, APS, APLS) by Jean G. Bustamante; Amandeep Goyal; Pankaj Bansal; Mayank Singhal. Last Update: July 4, 2020. From StatPearls:

Introduction

Antiphospholipid antibodies are autoantibodies that are directed against phospholipid-binding proteins. Antiphospholipid syndrome (APLS) is a multisystemic autoimmune disorder. The hallmark of APLS comprises the presence of persistent antiphospholipid antibodies (APLA) in the setting of arterial and venous thrombus and/or pregnancy loss. The most common sites of venous and arterial thrombosis are the lower limbs and the cerebral arterial circulation, respectively. However, thrombosis can occur in any organ.

To identify APLA, the laboratory tests include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and functional assays. The three known APLA are:

History and Physical

The clinical features vary significantly and can be as mild as asymptomatic APLA positivity, or as severe as catastrophic APLS. Arterial and venous thrombosis and pregnancy-related complications are the hallmarks of the disease. However, several other organ systems may be involved (non-criteria manifestations).

Vascular Thrombosis

APLS can cause arterial and/or venous thrombosis involving any organ system. APLS related thrombotic events can occur without preceding risk of thrombosis. They can be recurrent and can involve vessels unusual for other-cause-thrombosis (such as upper extremity thrombosis, Budd-Chiari syndrome, and sagittal sinus thrombosis). Venous thrombosis involving the deep veins of lower extremities is the most common venous involvement and may lead to pulmonary embolism resulting in pulmonary hypertension. Any other site may be involved in venous thrombosis, including pelvic, renal, mesenteric, hepatic, portal, axillary, ocular, sagittal, and inferior vena cava.

Arterial thrombosis may involve any sized arteries (aorta to small capillaries). The most common arterial manifestation of APLS is transient ischemic events (TIAs) or ischemic stroke, and the occurrence of TIA or ischemic stroke in young patients without other risk factors for atherosclerosis shall raise suspicion for APLS. Other sites for arterial thrombosis may include retinal, brachial, coronary, mesenteric, and peripheral arteries. The occurrence of arterial thrombosis carries a poor prognostic value, given the high risk of recurrence in these cases.

Pregnancy Morbidity

Pregnancy loss in patients with APLS is common, especially in the second or third trimester. While genetic and chromosomal defects are the most common cause of early (less than 10-week gestation) pregnancy loss, they may also occur in patients with APLS. Tripple positivity (lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin and anti-beta-2-glycoprotein-I antibodies), previous pregnancy loss, history of thrombosis, and SLE are risk factors for adverse pregnancy-related outcomes and pregnancy losses in APLS. Besides pregnancy losses, other pregnancy-related complications in APLS include pre-eclampsia, fetal distress, premature birth, intrauterine growth retardation, placental insufficiency, abruptio placentae, and HELLP syndrome (Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes, Low Platelet count).

Valvular Involvement

Cardiac valve involvement is very common in APLS, with some studies noting a prevalence as high as 80%. [10] Mitral and aortic valves are most commonly involved with thickening, nodules, and vegetations evident on echocardiography. This may lead to regurgitation and/or stenosis.

Hematological Involvement

Thrombocytopenia has been seen in more than 15% of APLS cases.[11] Severe thrombocytopenia leading to hemorrhage is rare. Positive Coomb test is frequently seen in APLS, although hemolytic anemia is rare.

Neurological Involvement

The most common neurological complication of APLS includes TIAs and ischemic stroke, which may be recurrent, leading to cognitive dysfunction, seizures, and multi-infarct dementia. Blindness secondary to the retinal artery or vein occlusion can occur. Sudden deafness secondary to sensorineural hearing loss has been reported.

Pulmonary Involvement

Pulmonary artery thromboembolism from deep vein thrombosis is common and may lead to pulmonary hypertension. Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage resulting from pulmonary capillaritis has been reported.

Renal Involvement

Hypertension, proteinuria, and renal failure secondary to thrombotic microangiopathy is the classic renal manifestation of APLS, although this is not specific to APLS. Other renal manifestations reported include renal artery thrombosis leading to refractory hypertension, fibrous intimal hyperplasia with organized thrombi with or without recanalization, and focal cortical atrophy.

Catastrophic Anti-Phospholipid Syndrome (CAPS)

CAPS is a rare but life-threatening complication of APLS, with less than 1% of patients with APLS developing CAPS. Mortality is very high (48%), especially in patients with SLE and those with cardiac, pulmonary, renal, and splenic involvement. It is characterized by thrombosis in multiple organs over a short period of time (a few days). Small and medium-sized arteries are most frequently involved. Clinical presentation varies depending on the organ involved and may include peripheral thrombosis (deep vein, femoral artery or radial artery), pulmonary (acute respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hemorrhage), renal (thrombotic microangiopathy, renal failure), cutaneous (livedo reticularis, digital ischemia, gangrene, skin ulcerations), cerebral (ischemic stroke, encephalopathy), cardiac (valve lesions, myocardial infarction, heart failure), hematological (thrombocytopenia), and gastrointestinal (bowel infarction) involvement.[12]

Preliminary criteria for the classification of CAPS were published in 2003. [13] The four criteria are:

Definite CAPS can be classified by the presence of all four criteria, while probable CAPS can be classified if 3 criteria are present and the fourth is incompletely fulfilled.

Catastrophic Anti-Phospholipid Syndrome (CAPS) Management

Early diagnosis is crucial in the management of CAPS due to the high mortality associated with it. There are no randomized controlled trials for the management of CAPS. Anticoagulation and high dose corticosteroids are used in combination with IVIG, plasmapheresis, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, or eculizumab.

Differential Diagnosis

Thrombosis due to antiphospholipid antibody syndrome must be differentiated from other causes of thrombosis such as hyperhomocysteinemia, factor V Leiden and prothrombin mutations, deficiency of protein C, protein S, or antithrombin III.

APLS associated nephropathy has to be differentiated from thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), vasculitis, hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), malignant hypertension, and lupus nephritis. A kidney biopsy is often needed to make a diagnosis in these cases.

Prognosis

Some European studies have observed 90% to 94% survival over ten years. However, morbidity is high in APLS, with more than 30% of patients developing permanent organ damage and more than 20% of patients developing severe disability at a 10-year follow-up. [17] Poor prognostic features include CAPS, pulmonary hypertension, nephropathy, CNS involvement, and gangrene of the extremities.

Overall the prognosis of both primary and secondary APLS is similar, but in the latter, the morbidity may be increased as a result of any underlying rheumatic or autoimmune disorder. Lupus patients with antiphospholipid antibodies carry a higher risk of neuropsychiatric disorders.

So with the above review in mind I now return to Dr. Farkas’ post Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome (CAPS) [Link To Podcast] [Link To Show Notes]:

Here are the direct links from Dr. Farkas’ post to each section of the chapter. So just review all of the notes. [Note to myself]

CONTENTS

- Pathophysiology

- Epidemiology & precipitating factors

- Clinical presentation

- Lab tests

- Tissue diagnosis

- Differential diagnosis

- Diagnostic criteria

- Treatment

- Summary

- Podcast

- Questions & discussion

- Pitfalls

- PDF of this chapter (or create customized PDF)

antiphospholipid syndrome

- This is a pro-coagulable condition caused by antibodies which bind to endothelial surfaces and trigger coagulation. Thrombosis may occur in arteries and/or veins.

- Antiphospholipid syndrome is more common in patients with lupus, but it can also occur on its own. It often presents with isolated large vessel vascular occlusions (e.g., DVT or PE).

acute derangement of coagulation

- Thrombocytopenia (60%)

- Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (20%)

- Lab features of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia include markedly elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), low haptoglobin, and schistocytes.

- Schistocytes, if present, are usually scanty (unlike the abundant numbers seen in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura).(29779928)

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (~25%)

- PTT prolongation due to lupus anticoagulant may be seen.

systemic inflammation

- Elevated ferritin levels (>1,000 ng/ml)

labs panel for investigation of possible CAPS:

- Anti-phospholipid antibodies (anti-cardiolipin IgG & IgM, anti-beta-2-glycoprotein type I IgG & IgM)

- Laboratory evaluation for lupus anticoagulant (e.g. beginning with measurement of PTT and dilute Russel Viper Vemon test; see figure above).

- Anti-Nuclear Antibody (ANA)

- Electrolytes, BUN/Cr

- Complete Blood Count with blood smear examination

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), haptoglobin

- D-dimer, coagulation studies

tissue diagnosis

- Definitive diagnosis of CAPS requires biopsy evidence of small vessel thrombosis, but this is often not possible (due to the patient’s instability and coagulation abnormalities).

- If skin lesions are present, these may be biopsied to demonstrate thrombosis.

- The risk/benefit ratio of pursuing biopsy of other organs is unknown. (29978552)

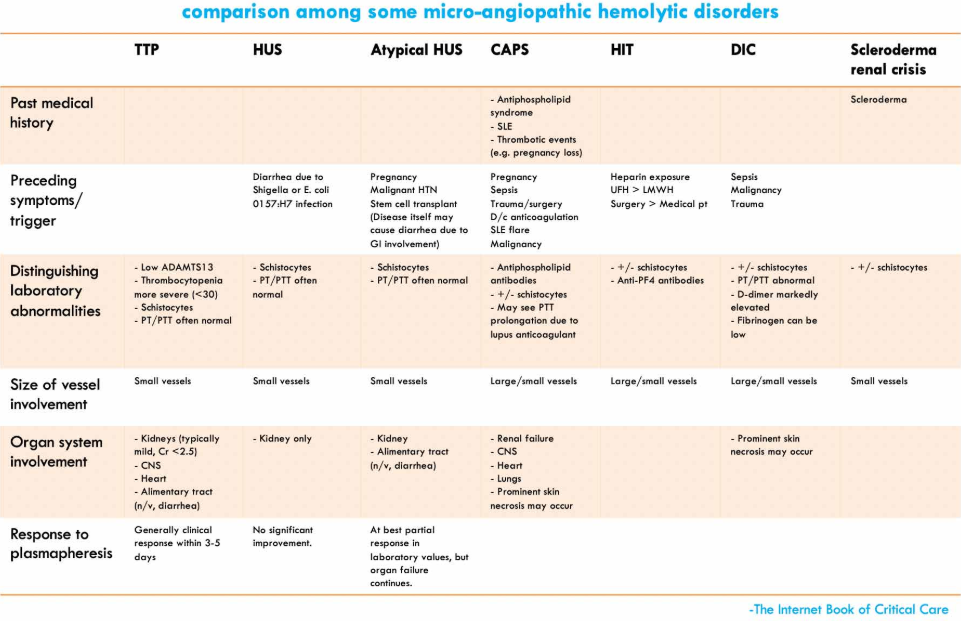

differential diagnosis

closest mimics of CAPS (30504326)

- Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

- Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) & atypical HUS

- Heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT)

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with purpura fulminans

- Medication-related microangiopathic syndromes

- Malignant hypertension

- Disseminated malignancy

- Sepsis

- Adrenal insufficiency (note: CAPS may cause adrenal insufficiency)

- Endocarditis

- Vasculitis

- Cholesterol emboli