Hypothetical Case: A 74 year old male diabetic on an insulin pump presented the office with the c/o of constant (for the last three weeks) frontal headache that at times shifted location to the right parietal area.

The patient’s past medical history revealed diabetes, CAD (MI in 1994 with a successful balloon angioplasty – asymptomatic with a recent normal pharmacologic nuclear stress test), hyperlipidemia (on atorvastatin), diabetic peripheral neuropathy (successfully treated on gabapentin).

His physical examination was normal including his neurologic exam (except for findings consistent with peripheral neuropathy).

His fundi could not be visualized as his pupils were small and he had mild cataracts.

So the question of increased intracranial pressure is raised.

What follows is a brief review of this topic based on a quick Google search. This post covers Resource (1). Resources (2 and 3) are reviewed in an upcoming post, The Imaging Evaluation of Suspected Increased Intracranial Pressure.

Resource (1) is a good brief general review of increased intracranial pressure. It covers both the acute presentation of increased intracranial pressure and the chronic presentation of increased intracranial pressure. What follows are excerpts from the paper:

Raised ICP is the final common pathway that leads to death or disability in most acute cerebral conditions. It is also potentially

treatable. The two major consequences of increased ICP are:

• brain shifts

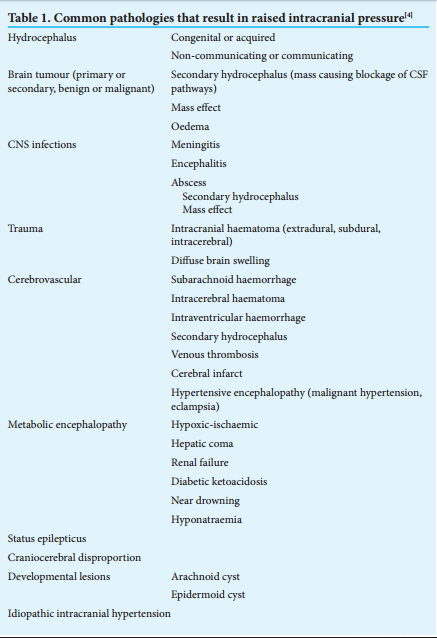

• brain ischaemiaSeveral conditions cause raised ICP, either by increasing one or more of the constituents of the intracranial cavity or by introducing a non-native mass to the cranial space (see

Table 1).Raised ICP is typically caused by one of the

following four mechanisms:

- cerebral oedema (brain tissue)

- vascular (congestive) brain swelling

- hydrocephalus (CSF)

- mass Lesion

- vascular (congestive) brain swelling hydrocephalus

Acutely increased ICP may present with rapidly deteriorating consciousness without focal neurological signs or papilloedema. Therefore absence of the latter does not exclude increased ICP. Meningism, commonly associated with the meningeal irritation of meningitis, may be mistaken for neck stiffness associated with impending tonsillar herniation. A lumbar puncture under these circumstances could prove fatal.

Headache, vomiting and visual disturbances [transient blurred vision lasting a few seconds] are common symptoms of raised ICP. Diplopia may occur due to cranial nerve palsies – the 6th cranial nerve is particularly vulnerable to stretch while the 3rd cranial

nerve is at risk because herniation of the medial temporal lobe through the tentorial notch stretches the nerve as it exits the midbrain. Palsy of the 3rd cranial nerve tends to be on the side of the lesion, whereas palsy of the 4th cranial nerve is non-localising.Several brain herniation syndromes have been described.[5] Should the patient present with any of these, urgent consultation with a neurosurgeon is mandatory.[These syndromes are well detailed on pp 3 + 4.]

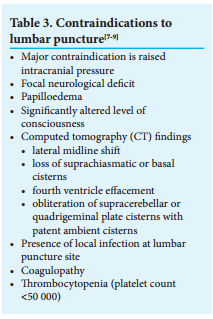

The presenting history and clinical situation should guide the choice of investigations. Invariably patients with a depressed level of consciousness will require imaging of the brain. The clinical situation determines how soon imaging should take place and the choice of imaging. In most cases, but not all, the diagnosis of raised ICP and the aetiology thereof are clear from the imaging. For trauma, an emergency CT of the head is performed as soon as the patient is resuscitated. If the presenting history includes a seizure, a contrast-enhanced CT or MRI will be more useful. If vascular pathology is suspected, angiography may also be indicated. When raised ICP is suspected for any reason, it is important not to perform a lumbar puncture prior to a CT scan that would indicate if it is probably safe to do so.

Management Of Acute Increased Intracranial Pressure

Identifying raised ICP and a possible aetiology, along with resuscitation of the patient where necessary, are the primary objectives of the initial treating physician.

The goals in the acute setting are resuscitation, imaging and neurosurgical referral. In an unconscious patient, manage

the patient according to Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocols. Intubate and ventilate the patient to protect their

airway if the GCS is 8 or less. An arterial blood gas will provide essential information regarding the patient’s oxygenation,

ventilatory and acid-base status. Avoid

hyper- and hypoventilation – it is safest

to aim for a PaCO2 of 4 – 4.5kPa. Ensure adequate systemic oxygenation: target an oxygen saturation of at least 95% or a PaO2 of at least 13 kPa. Maintain normal blood pressure – at all times avoid hypotension. Hypoxia and hypotension are potent secondary insults that worsen outcome. Be cautious about treating hypertension as this may be a Cushing’s response – the brain may be dependent on an elevated BP. Grade the

patient’s consciousness after ensuring that the patient is haemodynamically stable. A detailed neurological exam should follow, with particular attention paid to pupil size and light reaction, fundoscopy, cranial nerve palsies, long tract signs, and potential spinal cord injury in the setting of trauma. Place the patient with 15 – 30 degrees of head elevation in a neutral midline position to maximise cerebral venous return. Similarly,

avoid tight garments and tapings around the neck that cause jugular venous obstruction.Chronic Increased Intracranial Pressure

When chronic raised ICP is suspected, early imaging is once again a priority. Further management then depends on the probable definitive diagnosis.

See also my blog post The Imaging of Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension And Of Spontaneous Intracranial Hypotension Posted on March 2, 2017.

Resources:

(1) Raised intracranial pressure: What it is and how to recognise it [Download PDF]. 85 CME March 2013 Vol. 31 No. 3.

Please note that effective from January 2014, CME will be incorporated into a ‘new-look’ South African Medical Journal (available at www.samj.org.za). A review article will introduce readers to the educational subject matter along with one-page summarises of additional articles that may be accessed online only. We will continue to offer topical and up-to-date continuing medical educational material via the South African Medical Journal.

(2) Differential Diagnosis + Appropriate Imaging Evaluation Of Headache – Help From the ACR

Posted on March 2, 2017 by Tom Wade MD

(3) Imaging of Intracranial Pressure Disorders [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Neurosurgery. 2016 Jul 27. [Epub ahead of print]

(4) Case Report: Elevated Intracranial Pressure Diagnosis with Emergency Department Bedside Ocular Ultrasound [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2015;2015:385970. doi: 10.1155/2015/385970. Epub 2015 Oct 26.

Case Reports in Emergency Medicine is a peer-reviewed, Open Access journal that publishes case reports in all areas of emergency medicine.