Today, I review and excerpt from the Equality Section of

- The “5Es” of emergency physician-performed focused cardiac ultrasound: a protocol for rapid identification of effusion, ejection, equality, exit, and entrance [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Acad Emerg Med. 2015 May;22(5):583-93. doi: 10.1111/acem.12652. Epub 2015 Apr 22.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Equality

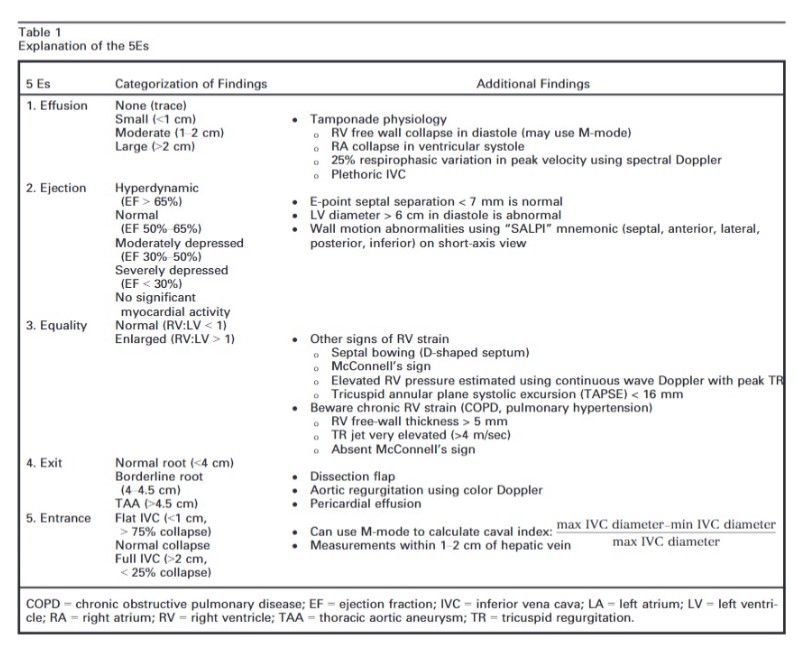

The third “E” in our protocol is for equality, referring to the relative size of the RV to the LV. In healthy patients, the RV is a low-pressure, thin-walled, high-compliance chamber that is wrapped anteriorly around the muscular, cone-shaped LV. The normal RV systolic pressure is approximately 25 mm Hg with an RV:LV diameter ratio of less than 0.6:1. When pressure in the pulmonary artery rises, the RV will dilate (Figure 5). While not perfectly sensitive, using “equality” (i.e., a 1:1 ratio) as the cutoff ensures specificity for detecting true RV strain by EP FOCUS.33, 34

Right ventricle dilatation may be acute, chronic, or acute-on-chronic. However, in patients presenting with undifferentiated chest pain, shortness of breath, hypotension, or syncope, the presence of any RV dilatation should raise the diagnostic suspicion of an acute pulmonary embolism (PE). PEs can range in severity from small subsegmental disease with minimal morbidity and mortality, to massive with resultant RV failure, shock, and death. PEs are typically defined as “massive” when sustained hypotension ensues. The remaining PE categories are stratified into “submassive,” when there are signs of RV strain on echo, versus “low-risk” (also labeled “small” or “minor”), when there is no RV strain.35 EP FOCUS can help stratify these patients, with RV hypokinesis being an independent predictor of mortality.36 The presence of RV strain in suspected massive PE or diagnosed submassive PE may signal the need for more aggressive therapy such as thrombolysis or thrombectomy.35, 37–39

Techniques for Assessing Equality

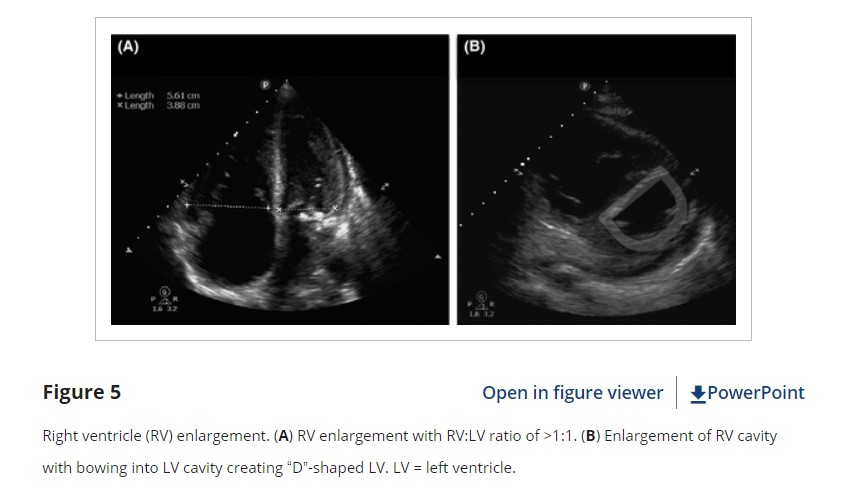

When the A4C view is properly obtained, with all four chambers visible and divided by a vertically oriented interventricular septum, ventricular size can be accurately compared either qualitatively or quantitatively (Figure 5). If measured, ventricular size should be obtained between endocardial borders at the tips of the valves in diastole. However, the A4C may be technically challenging to obtain correctly. The PSLA window may show a prominent and hypokinetic anterior chamber when RV strain is present. However, tilting of the plane in the PSLA (known as the “tricuspid tilt”) may cut across the RV obliquely causing overemphasis of the RV relative to the LV and should be used with caution. On the other hand, the PSSA at the level of the papillary muscles can often provide an excellent and reliable estimation of RV:LV ratio. In the PSSA view, the greatest chamber diameters for both the RV and the LV are usually visible side by side at the level of the papillary muscles. When RV pressure rises the septum will be pushed toward the LV. The PSSA is thus the preferred view to demonstrate this septal flattening, resulting in the characteristic “D-shaped” LV (Figure 5).40 The subxiphoid view may also show RV enlargement, but should be used with caution as the RV may be overemphasized if the plane of the US cuts through it obliquely, and RV size should be confirmed in other planes.

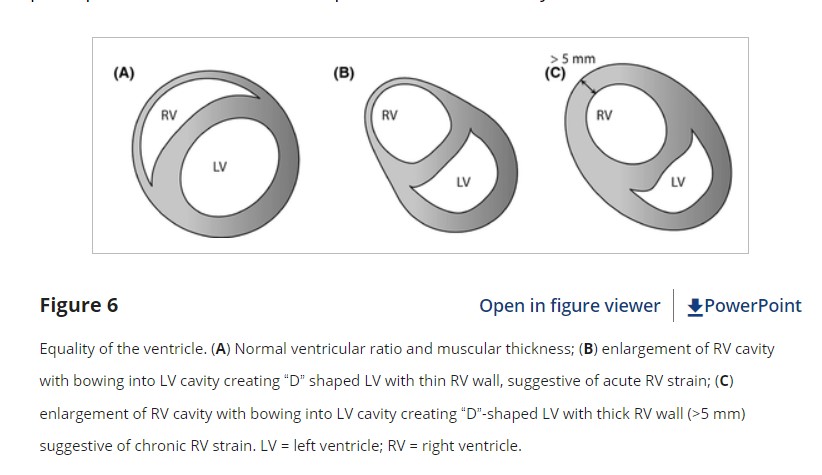

In addition to enlargement, EP FOCUS may show RV hypokinesis or be used to measure elevated RV pressure. While the LV tends to contract circumferentially and perpendicular to the long axis of the heart, the RV tends to move longitudinally, from base to apex. The A4C is the best view to demonstrate the movement of the tricuspid annulus during RV systole, allowing assessment and measurement of tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE, Figure 6). A TAPSE of 18 mm or greater is typically considered normal.41 TAPSE* is a technique for assessing RV function that is well described in the cardiology literature, but to our knowledge only described once in the EP literature.42–45 In our experience it is easily measured when an adequate A4C view is present and has been described as reproducible and perhaps better than RV size as a predictor of PE severity.41, 43, 45

*Link to videos on TAPSE (Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion)

-

- How to Measure TAPSE Clarius Mobile Health. May 8, 2023. Tricuspid annulus plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) can be measured using m-mode on the tricuspid annulus. It is an easy way to evaluate RV systolic function.

- All about TAPSE! (Echocardiography) The Echo Lady.

Jun 18, 2020 English vídeos❤️

Hello guys, in this video im talking about TAPSE! What it is? and how to measure it?. This is a parameter we use to assess the right ventricular systolic function.

Right ventricle systolic pressure may be estimated quantitatively when tricuspid regurgitation is present. The peak velocity of the tricuspid regurgitant jet should be measured using continuous wave spectral Doppler with the Doppler signal in line with the jet (typically in an A4C view). The pressure difference between the RV and RA can then be estimated using the modified Bernoulli equation, with ΔP = 4 × V2. A velocity greater than 2.7 m/sec typically indicates elevated RV systolic pressure (Figure 6), with velocities of 4 m/sec or greater indicating chronic RV pressure overload.

Pearls and Pitfalls of Equality

One of the primary pitfalls of RV assessment is overestimation of RV to LV ratio (false-positive) based on the US plane cutting through the RV in an oblique plane that makes the RV look relatively larger than the LV. This can be an issue in the PSLA, SX4C, or A4C views. For apical views, be sure to slide the probe sufficiently lateral on the chest wall so that the probe lies over the point of maximum intensity and true apex. Flattening the plane to transect through the base of the heart avoids foreshortened chambers and misinterpretation of their sizes (Figure 4). For the PSLA view it is important to fan through the long axis of the heart to make sure the LV is maximized relative to the RV.

An understanding of probe marker orientation conventions and relative probe placement on the patient is essential because if reversed, the normally larger LV may be mistaken for an abnormally enlarged RV (or an enlarged RV may be mistaken for a normal LV), especially in the A4C view.9

When imaged correctly by an EP with appropriate experience in echo, the presence of an RV:LV ratio of 1:1 or greater is highly specific for RV strain, as determined by consultant-performed echo.33, 34 However, because using a 1:1 ratio for a dilated RV sets a higher threshold (specificity) for pathology, sensitivity is sacrificed.35 Additionally, it is important to keep in mind that PEs (albeit “small”) may occur without any signs of right heart strain at all.

Right ventricle dilation may be a result of acute, chronic, or acute-on-chronic RV pressure elevation. While differentiation between these entities can be challenging, there are a few clues that may be available using both two-dimensional imaging and Doppler.

With acute right heart dilation the RV wall remains thin, but over time the RV will hypertrophy. If the RV free wall myocardium measures over 5 mm, this is indicative of chronic strain (Figure 6 above)

Furthermore, while both acute and chronic conditions produce measurable right heart pressure elevations, the acutely strained, thin-walled RV will not be able to generate extremely high pressures. A pressure gradient of more than 60 mm Hg (tricuspid regurgitation jet of about 4 m/sec or more) indicates chronic RV pressure elevation. McConnell’s sign, the presence of RV dilation and hypokinesis of the mid and basal portions of the RV with “apical sparing” (as opposed to global RV dysfunction), has been reported to be specific for acute RV strain, although it may not differentiate well between acute strain from PE versus acute strain from RV infarction.37, 46–4

Conclusions

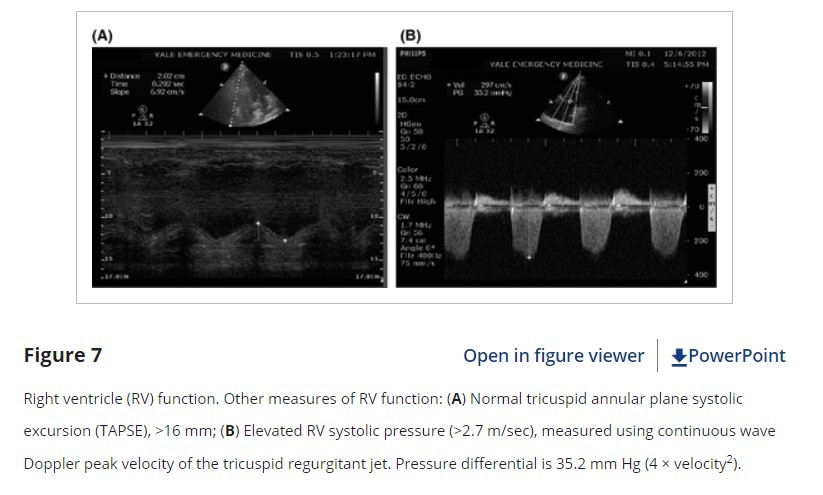

The intent of this article is to codify elements of the cardiac US exam that we have found to be most relevant to patients presenting with acute or emergent complaints (Table 1). A recent international consensus statement defined FOCUS as being goal-directed, problem-oriented, limited in scope, simplified, time-sensitive and repeatable, qualitative and semiquantitative, performed at the point of care, and usually performed by clinicians.6 The 5Es described in this article meet all of these criteria. However, the international statement addressed the use of FOCUS in “all clinical settings” and included the assessment of chronic cardiac disease, as well as gross valvular abnormalities and large intracardiac masses, without assessment of the thoracic aorta.

In our experience the 5Es encompass the cardiac US findings most applicable in patients who present emergently with hypotension, dyspnea, syncope, penetrating thoracic trauma, chest pain, or other acute complaints where diagnosis may be aided by visualization of the heart. While gross valvular abnormalities and intracardiac masses are important if they are seen, they are less common and less acute and tend to be less immediately deadly than acute thoracic aortic disease, which accounts for more than twice as many deaths as abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture.51The 5Es are not meant to provide an absolute boundary for EP FOCUS, which will likely continue to evolve, but are intended to provide a framework for the acquisition and interpretation of the most relevant and applicable components of echocardiography in the emergent setting. We hope that adoption and subsequent application of the 5Es in EDs will help to standardize and effectively teach the echo findings that may allow EPs to save lives and expedite the care of patients with potentially life-threatening illness. We thank Jane Hall, PhD, for preparing Figures 4, 6, and 8. We also thank Daniel Wadsworth Groves, MD, for manuscript review.