Here is the link to and excerpts from 5 Pearls On Hepatic Encephalopathy from CoreIM.

In addition to the above, see Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Hepatology. 2014 Aug;60(2):715-35. doi: 10.1002/hep.27210. Epub 2014 Jul 8.

Note to myself: I have included excerpts from the AASLD 2014 Guidelines above after the excerpts from the 5 Pearls.

Here are excerpts from 5 Pearls:

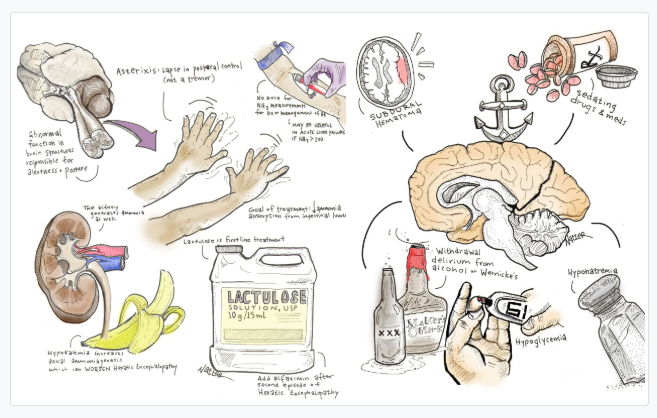

Big key is not to forget that other things besides hepatic encephalopathy can cause confusion in a cirrhotic. The bottom right of the above chart has some other causes to consider.

Show Notes

Pearl 1:

- Try not to anchor on hepatic encephalopathy in an altered cirrhotic patient.

- Examples of other common conditions that depress consciousness and tend to be misdiagnosed as HE include subdural hematomas, wernicke’s encephalopathy, sedating drugs and medications, withdrawal delirium from alcohol or benzodiazepines, hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, SBP, Co2 narcosis, etc.

- Common precipitating factors for acute hepatic encephalopathy:

- Medication nonadherence

- Infection

- Increased generation of ammonia, such as during a GI bleed or increased azotemia from overdiuresis, volume depletion or acute renal insufficiency

- Decreased liver clearance of ammonia, such with alcoholic hepatitis, portal vein thrombosis, HCC or increased shunting after a TIPS

- Electrolytes disturbances

Pearl 2:

- Asterixis = lapse in postural control, not a tremor. There are many ways to check for it.

- Asterixis reflects an abnormal function in brain structures responsible for alertness and posture.

- Asterixis can be seen in any form of toxic-metabolic encephalopathy, and even in thalamic/BG lesions and NOT specific to cirrhosis.

- Asterixis is only one symptom of hepatic encephalopathy; changes in cognition, affect, personality, and arousal are equally important.

Pearl 3:

- The goal in treatment is to reduce ammonia absorption from the intestinal lumen.

- In addition to treating reversible causes, there are two major categories of treatments: antibiotics and disaccharides

- Lactulose is first-line for both treatment of HE and for prevention of recurrence.

- AASLD’s recommendation is to add rifaximin to lactulose after the second episode of HE (grade 1 A recommendation).

Pearl 4:

- The kidney also generates ammonia. Hypokalemia increases renal ammoniagenesis and can precipitate or worsen HE.

- Correcting hypokalemia in HE is essential.

Pearl 5:

- There is no role for NH3 measurements in diagnosis or management of HE.

- There might be a role in acute liver failure where an arterial NH3 >200 is associated with higher risk of cerebral edema and herniation.

Here are excerpts from the 2014 AASLD Guidelines On Hepatic Encephalopathy:

Definition of HE

Hepatic encephalopathy is a brain dysfunction caused

by liver insufficiency and/or PSS [porto-systemic shunt]; it manifests as a wide spectrum of neurological or psychiatric abnormalities ranging from subclinical alterations to coma.Epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of HE are related to

the severity of the underlying liver insufficiency and

PSS.12-15 In patients with cirrhosis, fully symptomatic

overt HE (OHE) is an event that defines the decompensated phase of the disease, such as VB or ascites.7 Overt hepatic encephalopathy is also reported in subjects without cirrhosis with extensive PSS.8,9The risk for the first bout of OHE is 5%-25% within 5 years after cirrhosis diagnosis, depending on the presence of risk factors, such as other complications to cirrhosis (MHE or CHE, infections, VB, or ascites) and probably diabetes and hepatitis C.28-32

After TIPS, the median cumulative 1-year incidence of OHE is 10%-50%36,37 and is greatly influenced by the patient selection criteria adopted.38 Comparable data were obtained by PSS surgery.39

Clinical Presentation

Hepatic encephalopathy produces a wide spectrum of

nonspecific neurological and psychiatric manifestations.10

In its lowest expression,43,44As HE progresses, personality changes, such as apathy,

irritability, and disinhibition, may be reported by the patient’s relatives,47 and obvious alterations in consciousness and motor function occur.Patients may develop progressive disorientation to time and space, inappropriate behavior, and acute confusional state with agitation or somnolence, stupor, and, finally, coma.51

Classification

Hepatic encephalopathy should be classified according to all of the following four factors.10

1. According to the underlying disease, HE is subdivided into

- Type A resulting from ALF [Acute Liver Failure]

- Type B resulting predominantly from portosystemic bypass or shunting

- Type C resulting from cirrhosis

The clinical manifestations of types B and C are similar, whereas type A has distinct features and, notably, may be associated with increased intracranial pressure and a risk of cerebral herniation. The management of HE type A is described in recent guidelines on ALF62,63 and is not included in this document.

2. According to the severity of manifestations. The

continuum that is HE has been arbitrarily subdivided. For clinical and research purposes, a scheme of such grading is provided (Table 2). Operative classifications that refer to defined functional impairments aim at increasing intra- and inter-rater reliability and should be used whenever possible.Start here