In this post, I link to and excerpt from Diagnosis of Early Alzheimer’s Disease: Clinical Practice in 2021 [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2021;8(3):371-386. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2021.23.

The above resource has been cited by 42 articles in PubMed.

There are 111 similar articles in PubMed.

All that follows is from the above resource.

From The Abstract

The early and accurate detection of Alzheimer’s disease-associated symptoms and underlying disease pathology by clinicians is fundamental for the screening, diagnosis, and subsequent management of Alzheimer’s disease patients.

This review summarizes the importance of establishing an early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, related practical ‘how-to’ guidance and considerations, and tools that can be used by healthcare providers throughout the diagnostic journey.

From The Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia and is thought to account for 60–80% of dementia cases (3).

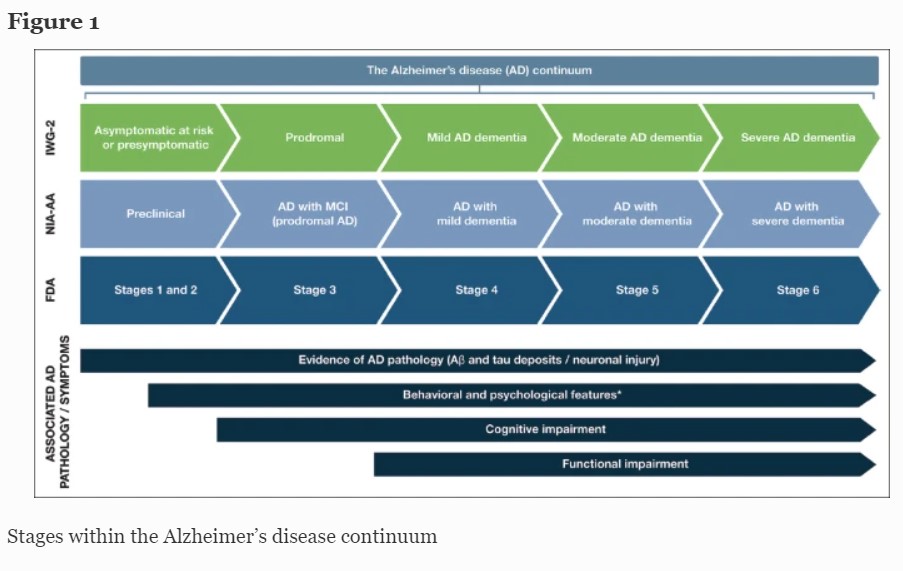

AD follows a progressive disease continuum that extends from an asymptomatic phase with biomarker evidence of AD (preclinical AD), through minor cognitive (mild cognitive impairment [MCI]) and/or neurobehavioral (mild behavioral impairment [MBI]) changes to, ultimately, AD dementia. A number of staging systems have been developed to categorize AD across this continuum (7–9). While these systems vary in terms of how each stage is defined, all encompass the presence/absence of pathologic Aβ and NFTs, as well as deficits in cognition, function, and behavior (7–9). As a result, subtle but important differences exist in the nomenclature for each stage of AD depending on the selected clinical and research classifications (Figure 1).

This figure provides a summary of the different naming conventions that are used within the AD community and the symptoms associated with each stage of the continuum; *Mild behavioral impairment is a construct that describes the emergence of sustained and impactful neuropsychiatric symptoms that may occur in patients ≥50 years old prior to cognitive decline and dementia (112); Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid beta. AD, Alzheimer’s disease. FDA, Food and Drug Administration. IWG, International Working Group. MCI, mild cognitive impairment. NIA-AA, National Institute on Aging—Alzheimer’s Association

Preclinical AD, as the earliest stage in the AD continuum, comprises a long asymptomatic phase, in which individuals have evidence of AD pathology but no evidence of cognitive or functional decline, and their daily life is unaffected (8) (Figure 1).

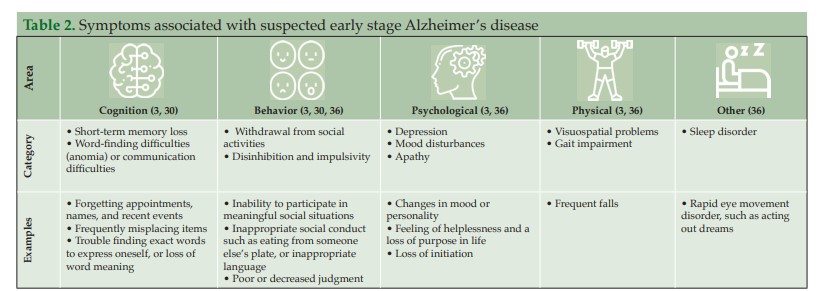

For patients who do progress to MCI due to AD (with/without MBI), initial clinical symptoms typically include short-term memory impairment, followed by subsequent decline in additional cognitive domains (15) (Figure 1). On a day-to-day basis, an individual with MCI due to AD may struggle to find the right word (language), forget recent conversations (episodic memory), struggle with completing familiar tasks (executive function), or get lost in familiar surroundings (visuospatial function) (15, 16). As individuals have varying coping mechanisms and levels of cognitive reserve, patients’ experiences and symptomology vary widely; however, patients tend to remain relatively independent at this stage, despite potential marginal deficits in function. The prognosis for patients with MCI due to AD can be uncertain; one study that followed up patients with MCI due to AD for an average of 4 years found that 43.4% progressed to AD dementia (12).

Excerpts From Practical guide for an early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in clinical practice

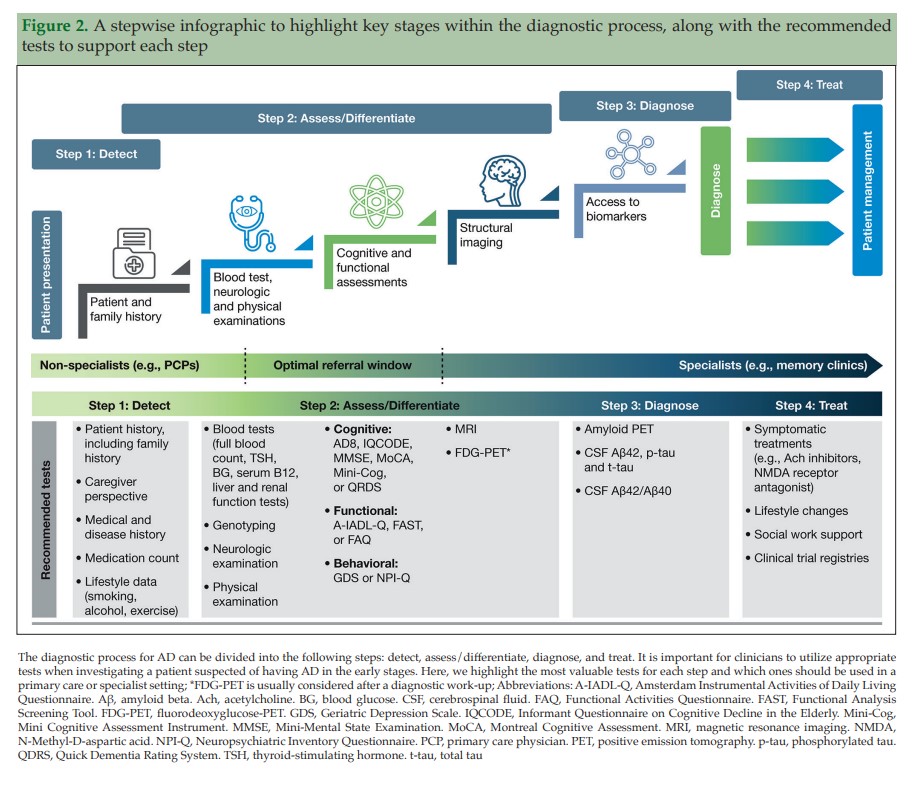

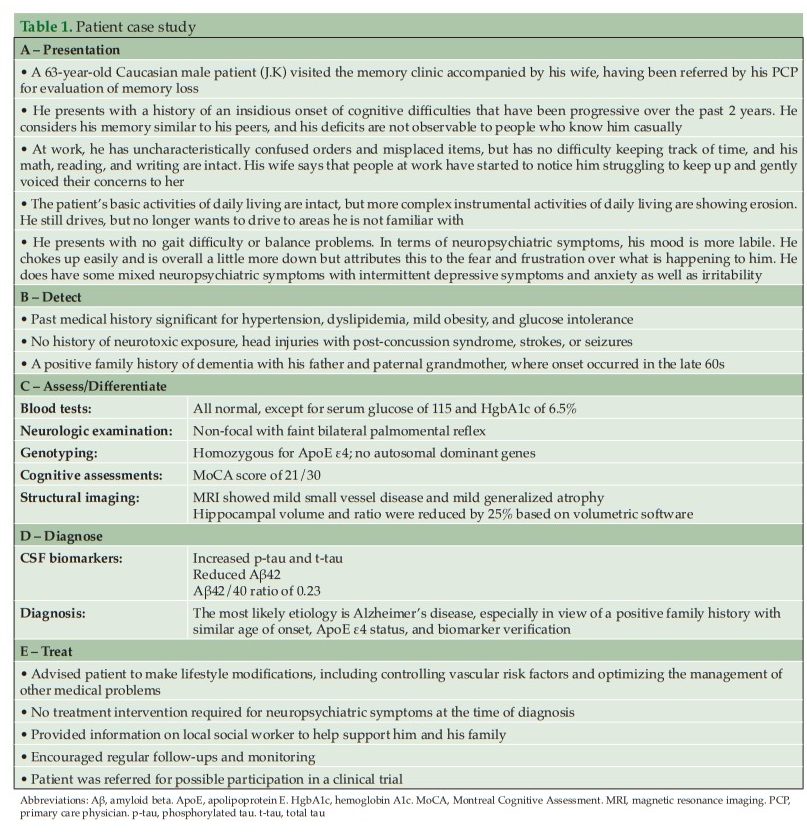

The recommendations include dividing the diagnosis of AD into the following steps: detect, assess/differentiate, diagnose, and treat (Figure 2). We present here a practical guide for the early diagnosis of AD, based on this outlined approach, including a case study to highlight each of these key steps.

Step 1: Detect

The role of primary care in the early detection of AD

Step 2: Assess and differentiate

Primary care: Initial assessment when a patient presents

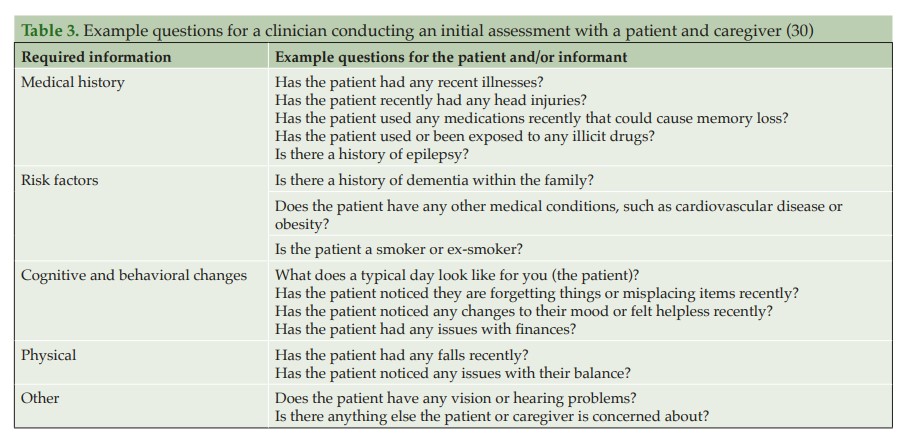

When a patient initially presents with symptoms consistent with early stages of AD, a clinician must first conduct a comprehensive clinical assessment to rule out other potential non-AD causes of cognitive impairment (Figure 2).

Primary care: Physical examination and blood analyses

A physical examination and blood tests can identify comorbid contributory medical conditions and reversible causes of cognitive impairment. A physical examination, including a mental status and neurological assessment, should be conducted to detect conditions such as depression and, for example, to look for signs such as issues with speaking or hearing as well as signs that could indicate a stroke (37). As part of the physical exam, a physician may ask the patient about diet and nutrition, review all medications (to see if these are the cause of any cognitive impairment, e.g. anti-cholinergics, analgesics, or sleep aids and anxiolytics), check blood pressure, temperature and pulse, and listen to the heart and lungs (36, 39).

Blood tests can rule out potentially treatable illnesses as a cause of cognitive impairment, such as vitamin B12 deficiency or thyroid disease (37). Suggested blood analyses include: 1) complete blood cell count; 2) blood glucose; 3) thyroid-stimulating hormone; 4) serum B12 and folate; 5) serum electrolytes; 6) liver function; and 7) renal function tests (30). Although not routinely used in clinical practice, clinicians may request ApoE genotyping, as this can help assess the genetic risk of developing AD. ApoE is the dominant cholesterol carrier within the brain that supports lipid transport and injury repair (40, 41), and the APOE gene exists as three polymorphic alleles: APOE ε2, ε3, and ε4. The ε4 allele of ApoE is associated with increased AD risk, whereas the ε2 allele is protective (40, 42). The number of ApoE ε4 alleles a person carries increases their risk of developing AD and the age of disease onset (43). Homozygous ε4 carriers (those with two copies of the ε4 allele) have the greatest risk of developing AD and the lowest average age of onset (43). In some practice settings, ApoE genotyping can only be conducted by a genetic counselor; a referral for more comprehensive genetic testing may be considered by the HCP if there is a family history of early-onset AD or dementia. Consumer tests are also becoming more readily available for patients wanting to determine their risk of developing diseases such as AD based on genetic risk factors (44).

Primary care: Cognitive, functional, and behavioral assessments

Cognitive assessments

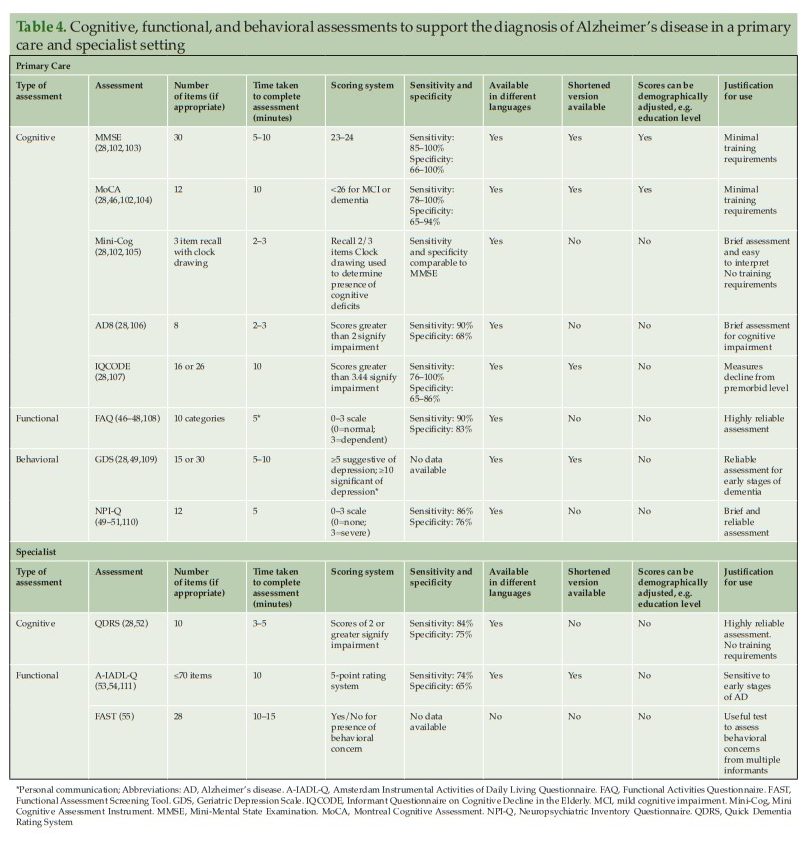

If a patient is suspected of having AD following an initial assessment in primary care, and they are <65 years old, or if the case is complex, a referral to a dementia specialist such as a neurologist, geriatrician, or geriatric psychiatrist may be required for further evaluation. The specialist would then use an appropriate battery of cognitive, functional, and behavioral tests to assess the different aspects of disease, and ultimately to confirm diagnosis. However, not all patients with suspected cognitive deficits are immediately referred to a dementia specialist at this stage, which is only partly due to limited numbers of specialists (25) (Figure 2). In clinical practice, a two-stage process is often employed. This involves an initial ‘triage’ step conducted by non-specialists to clinically assess and select those patients who require further evaluation by a dementia specialist (45). During this ‘triage’ step, there are several clinical assessments available to non-specialists for assessing the presence of cognitive and functional impairments and behavioral symptoms (Table 4) (28, 35, 46–55).

Cognitive assessments that can be conducted quickly (<10 minutes), such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), can be used by non-specialists to identify the presence and severity of cognitive impairment in patients before referring to a dementia specialist (Table 4) (36). Both the MMSE and MoCA are used globally in clinical practice, particularly in primary care, but vary in terms of their sensitivity to identify AD in the early stages (28, 59). The MMSE is sensitive and reliable for identifying memory and language deficits in general but has limitations in identifying impairments in executive functioning (59). MoCA was originally developed to improve the detection of MCI (28) and is more sensitive than the MMSE in its assessment of memory, visuospatial, executive, and language function, and orientation to time and place (59). Both tests are relatively easy to administer and take around 10 minutes to complete. Neither assessment requires extensive training by the clinician, although MoCA users do need to undergo a 1-hour certification as mandated by the MoCA Clinic and Institute (28, 60).

For time-constrained clinicians, the Mini Cognitive Assessment Instrument (Mini-Cog) may be an appropriate tool to assess cognitive deficits that focus on memory, and components of visuospatial and executive function (Table 4). The assessment includes the individual learning three items from a list, drawing a clock, and then recalling the three-item list. The Mini-Cog can be useful for clinicians in primary care, as it requires no training and the results are easy to interpret. As an alternative to these tests, PCPs might also consider using an informant-based structured questionnaire such as the AD8 or Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly to help guide discussions with the patient and caregiver (Table 4) (28).

Functional assessments

Functional assessments are valuable in identifying changes in a patient’s day-to-day functioning through the evaluation of their instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). IADLs are complex activities that are necessary for the individual to function independently (e.g., cooking, shopping, and managing finances) and can be impaired during the early stages of cognitive impairment. . . . Consequently, functional independence is one of the most important clinical features for patients with AD. As the disease progresses, and patients have increasing functional impairment, this significantly impacts on their independence, and subsequently their and their family/caregiver’s quality of life.

Functional assessment is, therefore, an integral part of the diagnostic process for AD. The Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) is an informant questionnaire that assesses the patient’s performance over a 4-week period and may take only a few minutes to complete (Table 4). The questionnaire is scored from ‘normal’ to ‘dependent’, using numerical values assigned to categories, with higher scores indicative of increasing impairment (47). Previous research has shown that the FAQ has high sensitivity and reliability for detecting mild functional impairment in patients with MCI (47).

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [Long Form] [Short Form] and Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) can be used by clinicians to assess neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients for whom early-stage AD is suspected (Table 4). The GDS is a 15-item (or longer 30-item) questionnaire that assesses mood, has good reliability in older populations for detecting depression, and can be completed by the patient within 5–10 minutes (63). The NPI-Q can be used in conjunction with or as an alternative to the GDS. The NPI-Q is completed by a knowledgeable informant or caregiver who can report on the patient’s neuropsychiatric symptoms. The NPI-Q can be conducted in around 5 minutes to determine both the presence and severity of symptoms across several neuropsychiatric domains including depression, apathy, irritability, and disinhibition (49). Consequently, as it assesses depression, it can be used as an alternative to GDS if time constraints do not allow for both to be completed.

Behavioral symptoms can be non-specific, so it is important for clinicians to consider and rule out other potentially treatable causes of impairment when assessing this domain. For example, depression is associated with concentration and memory issues (64); apathy can occur in non-depressed elderly individuals and can impact cognitive function (65). Signs/symptoms such as social withdrawal, feelings of helplessness, or loss of purpose should be investigated closely, as these could be indicative of depression alone. It is important for clinicians to recognize that if changes over time in cognitive symptoms and mood symptoms match, then depression is most likely to be the root cause of subtle cognitive decline, rather than AD (28).

Primary care clinician checklist

If AD is still suspected following clinical assessment, referral to a specialist for further diagnostic testing, including imaging and fluid biomarkers, may be required. It is important the clinician confirms the following checks/assessments before the patient undergoes further evaluation:

Primary care clinician checklist

- Confirm medical and family history

- Review the patient’s medications for any that could cause cognitive impairment

- Perform blood tests to eliminate potential reversible causes of cognitive impairment

- Conduct a quick clinical assessment to confirm the presence of cognitive impairment

Specialist role in assessment

Following the initial assessment in primary care, further cognitive, behavioral, functional, and imaging assessments can be carried out in a specialist setting. With their additional AD experience, access to other specialties, and possibly fewer time constraints than the PCP, the specialist is able to conduct a more comprehensive testing battery, using additional clinical assessments and biomarkers to determine causes of impairment and confirm diagnosis (Figure 2).

Cognitive assessments

Because the cognitive impacts of early-stage AD may vary from patient to patient, it is important to consider which cognitive domains are affected in these early stages when considering which assessments to use.

Specialists are able to conduct a full neuropsychological test battery* that covers the major cognitive domains (executive function, social cognition/emotions, language, attention/concentration, visuospatial and motor function, learning and memory); preferably, a battery should contain more than one test per domain to ensure adequate sensitivity in capturing cognitive impairment (66)**. This step can help with obtaining an in-depth understanding of the subtle changes in cognition seen in the early stages of AD and enables the clinician to monitor subsequent changes over time.

*Neuropsychological Assessment

Lynn A. Schaefer; Tanu Thakur; Michael R. Meager. Last Update: May 16, 2023. From StatPearls.

**Version 3 of the Alzheimer Disease Centers’ Neuropsychological Test Battery in the Uniform Data Set (UDS) [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2018 Jan; 32(1): 10–17.

Published online 2018 Feb 26. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000223

Typically, episodic memory, executive function, visuospatial function, and language are the most affected cognitive domains in the early stages of AD (29, 67, 68). Currently, most cognitive assessment tools focus on a subset of the overall dimensions of cognition; it is therefore vital the clinician chooses the correct test to assess impairment in these specific cognitive domains that could be indicative of AD in the early stages. As cognitive impairment in the early stages of AD can be subtle and vary significantly between individuals (29), clinicians must choose appropriate, sensitive tests that can detect these changes and account for a patient’s level of activity and cognitive reserve (29). If there is large disparity in results across cognitive assessments, it is important for the clinician to shape their assessments based on the patient’s history. If the patient’s history is positive for neurodegenerative disease, but one assessment does not reflect this, it is important to conduct further tests to ascertain the cause of the cognitive impairment.

The Quick Dementia Rating System (QDRS) can be used by specialists to assess cognitive impairment (Table 4). This short questionnaire (<5 minutes) is completed by a caregiver/informant and requires no training. The QDRS assesses several cognitive domains known to be affected by AD, including memory, language and communication abilities, and attention. The questionnaire can reliably discriminate between individuals with and without cognitive impairment and provides accurate staging for disease severity (28).

Functional assessments

The Amsterdam IADL Questionnaire (A-IADL-Q) and Functional Assessment Screening Tool (FAST) can both be used to assess a patient’s functional ability (Table 4) (53). The A-IADL-Q is a reliable computerized questionnaire that monitors a patient’s cognition, memory, and executive functioning over time. This questionnaire is completed by an informant of the patient and takes 10 minutes to complete (53). For patients with suspected early stage AD, the A-IADL-Q is a useful tool to monitor subtle changes in IADL independence over time and is less influenced by education, gender, and age than other functional assessments (53). The FAST is a useful assessment for clinicians to identify the occurrence of functional and behavioral problems in patients with suspected AD. The questionnaire is completed by informants who interact with the patient regularly; informants are required to answer Yes/No to a number of questions focusing on social and non-social scenarios (55).

Structural imaging

Structural imaging, such as MRI, provides clinically useful information when investigating causes of cognitive impairment (69) (Figure 2). MRI is routinely conducted to exclude alternative causes of cognitive impairment, rather than support a diagnosis of AD (37, 70). It is well known that medial temporal lobe atrophy is the best MRI marker for identifying patients in the earliest stages of AD (70, 71); however, specific patterns of atrophy may also be indicative of other neurodegenerative diseases. Atrophy alone is rarely sufficient to make a diagnosis. MRI findings can help to narrow the differential diagnosis, and the results should be considered in the context of the patient’s age and clinical examination (69–71).