In this post I link to and excerpt from Emergency Medicine Cases‘ ECG Cases 8 Cardiovascular Emergencies During The COVID-19 Pandemic. Written by Jesse McLaren; Peer Reviewed and edited by Anton Helman. April 2020.

All that follows is from the above post.

In this ECG Cases blog we look at 6 patients who presented with cardiorespiratory symptoms, possibly from COVID

COVID-19 pandemic and cardiovascular emergencies

The COVID-19 pandemic poses a number of challenges for cardiovascular emergencies, and not only for COVID-19 patients. A review summarized this new and evolving field: “First, those with COVID-19 and preexisting cardiovascular disease (CVD) have an increased risk of severe disease and death. Second, infection has been associated with multiple direct and indirect cardiovascular complications including acute myocardial injury, myocarditis, arrhythmias and venous thromboembolism. The response to COVID-19 can compromise the rapid triage of non-COVID-19 patients with cardiovascular conditions. Finally, the provision of cardiovascular care may place health care workers in a position of vulnerability as they become host or vectors of virus transmission.”[1]

Acute cardiac injury (defined as abnormal troponin level) occurs in up to 20% of patients hospitalized for COVID-19, and is a marker of poor prognosis.[2] COVID-19 can cause acute cardiac injury through multiple mechanisms: “early reports indicate that there are two patterns of myocardial injury with COVID-19. The rise in hs-cTnI tracks with other inflammatory biomarkers (D-dimer, ferritin, interleukin-6, LDH), raising the possibility that this reflects cytokine storm. In contrast, reports of patients presenting with predominantly cardiac symptoms suggests a different pattern, potentially viral myocarditis or stress cardiomyopathy”[3] COVID-19 cardiac complications include both STEMI mimics like myocarditis (diagnosed retrospectively after a normal angiogram) [4] and concerns that the inflammatory response could cause plaque rupture leading to acute coronary occlusion (which the newly created North American COVID-19 ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Registry (NACMI) will help track).

Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 can develop pulmonary emboli[5], and the rate is especially high in critically ill patients in ICU [6]. But the incidence of patients presenting to the ED with both COVID-19 and PE is isolated to case reports. As a report on a patient presenting with pneumonia and hemoptysis, along with right-heart strain on the ECG, concluded: “An association between COVID-19 and PE creates a diagnostic challenge for emergency medicine clinicians given the overlap in symptoms between the two clinical entities. Elevated D-Dimer levels (>1.0 mg/dl) have been identified as a potential predictor of increased mortality, but are not specific to the diagnosis of VTE. Reliance on D-dimer as a screening tool should be discouraged in this patient population and may lead to over utilization of Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA)…In addition to clinical features like hemoptysis, signs of right heart strain on adjunctive bedside tests like EKG or point of care ultrasound maybe helpful for clinicians in identifying COVID-19 patients at risk for concurrent pulmonary embolism.”[7]

In addition, the scale of the pandemic appears to be impacting non-COVID cardiovascular emergencies. In a number of regions hit hard by the pandemic there’s been a paradoxical drop in the number of STEMI cases, raising the concern that patient fear of COVID-19 is leading to medical distancing; avoidance of hospitals could lead to early death or late presentations.[8] Early data from one hospital in Hong Kong found delays in STEMI patients seeking medical care, as well as delays in door-to-device times.[9] As an American College of Cardiology clinical bulletin warned, “classic symptoms and presentation of AMI may be overshadowed in the context of COVID-19, resulting in underdiagnosis.”[10] This is especially important in the ED, where patients present with undifferentiated symptoms and unknown COVID-19 status.Anchoring on a pandemic disease whose diagnosis is delayed and whose main treatment is supportive could lead to missing cardiovascular emergencies that can be quickly diagnosed at the bedside and for whom specific treatments exist, like PE and acute coronary occlusion. Finally, there are changing protocols around interventional cardiology, varying between and within countries over time (and some which reinforce the false dichotomy between STEMI and NSTEMI). The Canadian Association of Interventional Cardiology recommends decisions on PCI vs medical management be guided by diagnosis, clinical stability, likelihood of COVID-19 or known status, and resource restrictions.[11] Each centre may have a slightly different approach, which may change over time, and COVID-19 test results are helpful in planning non-urgent cases.

Six patients presented with cardio-respiratory symptoms, possibly COVID-19.

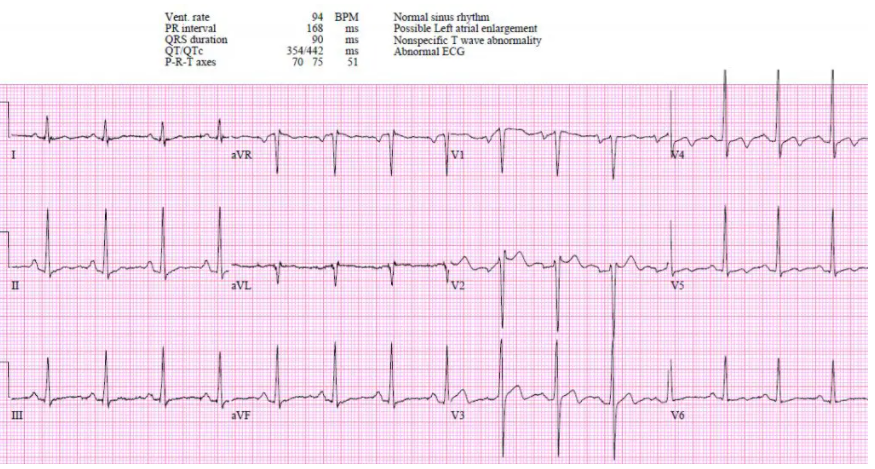

Patient 1: 50yo with sore throat and recent sick contact, woke up short of breath with throat tightness. RR 20, sat 95%, HR 105, BP 160/70

Patient 1: myocarditis, COVID(-)

ECG/trop done because of 50yo with SOB out of proportion to mild URTI symptoms.

- HR/rhythm: sinus tach

- Electrical conduction: normal

- Axis: normal

- R-wave: normal progression

- Tension: no hypertrophy

- ST-T waves: convex ST segment with terminal T wave inversion V3-4

Trop 19,000 and referred to cardiology. Normal echo and cath, and myocarditis diagnosed by cardiac MRI. Discharge ECG: normal V2 placement, normalizing ST morphology V2-3.