Note to myself: This EMC podcast is part one of a two part series on diagnosis of bradycardia. Next month’s post will cover the treatment of bradycardia

In this post I link to and excerpt from Emergency Medicine Cases‘ Ep 154: 4-Step Approach to Bradycardia and Bradydysrhythmias*.

*Helman, A. Hedayati, T. Dorian, P. Episode 154 – 4-Step Approach to Bradycardia and Bradydysrhythmias. Emergency Medicine Cases. April, 2021. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/approach-bradycardia-bradydysrhythmias. Accessed April 8, 2021.

All that follows is from the show notes.

4-step approach to bradycardia in the ED

These steps are often done in parallel.

- Stable vs. unstable

- Symptomatic vs. asymptomatic

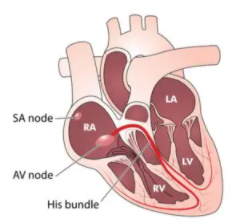

- Determine the anatomic location causing the bradycardia: SA node, AV node or His-Purkinje

- Assess for secondary causes of bradycardia

Step 1: Determine if bradycardia is stable or unstable requiring immediate treatment

The history and physical exam are paramount in helping make the decision of whether a patient with bradycardia is stable or unstable. Athletes and healthy people who are sleeping may normally have heart rates in the 30’s, so the heart rate alone is almost never a sign of instability, unless there is another factor at play: underlying vasodilation, negative inotropic effect or intrinsic cardiac disease. Nonetheless, be extra-weary in patients with progressive bradycardia or worsening bradycardia: 50s then 40s then 30s then 20s. This is a sign of pre-arrest.

Cardiac output is dependent on heart rate and stroke volume. Depressed cardiac output in the setting of overt bradycardic shock will manifest as hypotension, as well as signs of decreased organ perfusion such as altered mental status, chest pain, dyspnea or syncope – all signs of an “unstable” bradycardic patient. However, be cautious to not miss occult bradycardic shock where the vasoconstrictor response in the setting of bradycardia maintains ones blood pressure and mental status. The patient however may still have low cardiac output and thus be “unstable”. The clinical exam assessing for poor end-organ perfusion (altered LOA, cool extremities, low urine output etc) is critical in diagnosing occult bradycardic shock [compensated shock].

It is important to determine if the bradycardia is causing symptoms (an older patient with underlying cardiac disease with chest pain and syncope), or if symptoms are the cause for bradycardia (vasovagal bradycardia), as this will direct management.

Symptomatic bradycardia exists when the following 3 criteria are met:

- The HR is slow

- The patient has symptoms and

- The symptoms are due to the slow HR

Asymptomatic bradycardia generally does not require any emergency treatment.

Step 3: Determine the anatomic location causing the bradycardia

Correct identification of the location of the problem (SA node vs. A node vs. His Purkinje) guides management of bradycardia. Sinus and AV nodal dysfunction rarely leads to life-threatening complications and are treated with watchful waiting, atropine or sympathetic medications such as epinephrine and dopamine. However, distal His-Purkinje block is much more serious, and tend not to respond to atropine and sympathetic stimulation. These patients almost always need pacing and a definitive pacemaker.

Dr. Dorian’s approach to AV block: proximal vs. distal AV block

Our expert Dr. Dorian prefers to approach AV block by thinking about the location of the block, whether the block occurs in the proximal conducting system (AV node) or the distal conducting system (His-Purkinje). The reason why classifying AV block by 2nd degree Type 1 and 2 is less helpful is because there are instances where “high-grade” AV blocks such as 2:1 AV block (2 p waves for every 1 QRS – see image below) occurs secondary to intrinsic AV nodal disease and the treatment for these patients is generally conservative; whereas patients with distal AV block do not respond to atropine or sympathetic stimulation and need pacing.

The key to teasing apart where the conductive disease lies is looking for the rhythm preceding the onset of the block.

Key ECG clues that help differentiate proximal vs. distal AV block

Clues that suggest proximal AV block

- Sudden or progressive sinus bradycardia preceding the AV block with a story of high vagal tone

- Narrow QRS complex

- First conducted beat following the block is a shortened PR interval

Clues that suggest distal AV block

- Accelerated sinus beats prior to AV block

- Wide QRS complex

Common types of bradycardia and syndromes associated with bradycardia

- Sinus bradycardia

- Junctional bradycardia

- 1st Degree AV block

- 2nd Degree AV block

- Ventricular escape rhythm and complete heart block

- Tachy-brady syndrome

- Bradycardia-induced Torsades de Pointes

- BRASH Syndrome

The rest of the show notes for Step 3 contain an excellent clear approach to the diagnosis and hence ultimately the treatment of each of the above causes of bradycardia.

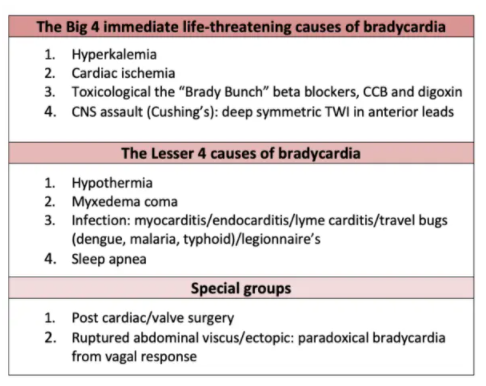

Step 4: Assess for reversible causes of bradycardia

80% of bradycardias are a secondary effect originating outside the cardiac conduction system. Asymptomatic, nocturnal or vagally induced bradycardia is most often benign and needs no specific treatment.

Always assess for easily reversible causes of bradycardias, the most common being AV nodal drugs, and high vagal tone.

The 4th step often needs to be done in parallel with steps 1-3 in order to rule out secondary cause or causes that if treated, may preclude the need for atropine, sympathetic stimulation and pacing. Identification of contributing factors for symptomatic bradycardia should be considered throughout the resuscitation since reversal of the cause will likely return the patient to a state of adequate perfusion.

If you prefer mnemonics to aid in recall of the differential diagnosis of bradycardia…

BRADI mnemonic for causes of bradycardia

- BRASH/hyperkalemia

- Isolated hyperkalemia

- BRASH syndrome (Bradycardia, Renal failure, AV node blockade, Shock and Hyperkalemia)

- Reduced vital signs

- Hypoxia

- Hypoglycemia

- Hypothermia +/- hypothyroid

- Acute coronary occlusion

- Inferior MI: nodal ischemia and vagal response, self-limiting or responds to atropine

- Anterior MI: infranodal ischemia, often requires pacing

- Drugs: withdraw if stable, reverse if unstable

- Beta-blockers

- Calcium channel blockers

- Digoxin

- Intracranial pressure, Infection (Lyme, endocarditis): treat underlying

Take home points on 4-step approach to bradycardia

- Be cautious with your history and physical exam to not miss occult bradycardic shock [Compensated Shock]

- Bradycardia alone rarely causes instability, with the exception of progressive bradycardia, which is a sign of pre-arrest

- Determine if symptoms are causing bradycardia (vasovagal) or if bradycardia is causing symptoms

- Identify location of problem – which will determine whether urgent pacing is required or not

- Is the QRS narrow? Indicating proximal (SA/AV node disease); Is the QRS wide? Proximal or distal (His Bundle disease)

- Assess rhythm prior to bradycardia: sinus brady more likely to be proximal, sinus tachycardia more likely to be distal disease

- Junctional bradycardia is most commonly caused by toxicity from AV node blockers, post valve surgery and inferior MI

- Tachy-brady syndrome occurs in the setting of elderly patient with paroxysmal afib; do not treat these patients with AV node blockers

- Torsades can occur in the setting of bradycardia with AV block, and these runs of polymorphic VT can degenerate into Vfib

- Concurrently rule out secondary causes of bradycardia by considering the “Big 4 life threats” and “Lesser 4” causes

Practice your identification of bradydysrhythmias in ECG Cases 20: Approach to Bradycardia and BRADI Mnemonic