In this post I link to and excerpt from Acute kidney injury 2016: diagnosis and diagnostic workup [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Crit Care. 2016; 20: 299.

Here are excerpts:

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a syndrome characterised

by a rapid (hours to days) deterioration of kidney function. It is often diagnosed in the context of other acute illnesses and is particularly common in critically ill patients. The clinical consequences of AKI include the accumulation of waste products, electrolytes, and fluid, but also less obvious effects, including reduced immunity and dysfunction of non-renal organs (organ cross-talk) [1].This review will summarise the key aspects of diagnosis and diagnostic work-up with particular focus on patients in the intensive care unit (ICU)

Diagnosis of AKI

The diagnosis of AKI is traditionally based on a rise in

serum creatinine and/or fall in urine output. The definition has evolved from the Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, End-stage (RIFLE) criteria in 2004 to the AKI Network (AKIN) classification in 2007 [4, 5]. In 2012, both were merged resulting in the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) classification [6].Accordingly, AKI is diagnosed if serum creatinine increases by 0.3 mg/dl (26.5 μmol/l) or more in 48 h or rises to at least 1.5-fold from baseline within 7 days (Table 1). AKI stages are defined by the maximum change of either serum creatinine

or urine output. The importance of both criteria was confirmed in a recent study in >32,000 critically ill patients which showed that short- and long-term risk of death or renal replacement therapy (RRT) were greatest when patients met both criteria for AKI and when these abnormalities persisted for longer than 3 days [7].

Use of both the serum creatinine and the urine output to diagnose acute kidney injury have limitations. See the article for details which are summarized in Table 2 below:

Diagnosis of acute kidney disease

AKI is defined as occurring over 7 days and CKD starts

when kidney disease has persisted for more than 90 days.

Based on epidemiological studies and histological case

series, it is clear that some patients have a slow but persistent (creeping) rise in serum creatinine over days or

weeks but do not strictly fulfil the consensus criteria for

AKI [47, 48].Diagnostic work-up

As a syndrome, AKI can have multiple aetiologies. In

critically ill patients, the most common causes are sepsis,

heart failure, haemodynamic instability, hypovolaemia,

and exposure to nephrotoxic substances [9].Acute parenchymal and glomerular renal diseases are relatively

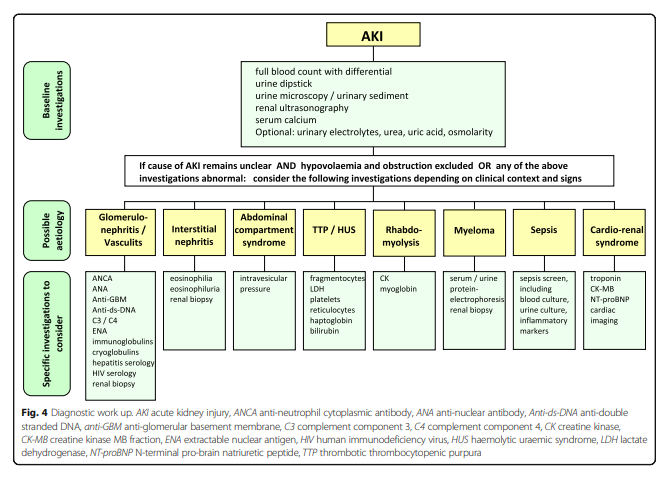

rare.The specific diagnostic workup in individual patients

with AKI depends on the clinical context, severity, and

duration of AKI, and also on local availability. Urinalysis, examination of the urinary sediment, and imaging studies should be performed as a minimum, with additional tests depending on the clinical presentation (Fig. 4).

Urine dipstick

Urine dipstick testing is a simple test to undertake. In

fact, the AKI guideline by the National Institute for

Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK recommends performing urine dipstick testing for blood, protein, leucocytes, nitrites, and glucose in all patients as soon as AKI is suspected or detected in order not to miss any potentially treatable glomerular or tubular pathologies [53].These include:

- glomerulonephritis (with haematuria and

proteinuria)- acute pyelonephritis (with pyuria/leucocyturia and

nitrites in urine)- interstitial nephritis (occasionally with

eosinophiluria)- [Dr. Topf in #226 Acute Kidney Injury from the Curbsiders reminds us that acute tubular necrosis is the most common cause of intrarenal acute kidney injury

- [AKI In the Critically Ill: In Dr. Topf’s experience, 9/10 of these patients are suffering from acute tubular necrosis (ATN)]

It is important to consider the result of the urine dipstick alongside the clinical history and an evaluation of the patient. For instance, the presence of white blood cells is non-specific but may indicate an underlying infection or acute interstitial nephritis.

Similarly, dipstick haematuria in a patient with an indwelling urinary catheter can have multiple aetiologies ranging from glomerulonephritis to simple trauma.

Dipsticks detect haemoglobin and remain positive even after red cell lysis. They also detect haemoglobinuria from intravascular haemolysis as well as myoglobin from muscle breakdown.

A urine dipstick positive for haemoglobin without red blood cell positivity suggests a possible diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis.

Urine microscopy (urinary sediment)

Urine microscopy can provide very valuable information when performed by a skilled operator using a freshly collected non-catheterised urine sample (Table 4). It is not utilized very often in the ICU predominantly because it is operator dependent and requires training and experience.

[See page 8 of the paper for more details on this topic.]

Insert fig4 when upload working.

Insert fig5 when upload working.

Renal ultrasound

Renal ultrasonography is useful for evaluating existing structural renal disease and diagnosing obstruction of the urinary collecting system. In particular, the presence of reduced corticomedullary differentiation and decreased kidney size is indicative of underlying CKD.

Measurement of intra-abdominal pressure

In case of suspected AKI due to intra-abdominal compartment syndrome, serial measurement of intra-abdominal pressure should be considered. Those with a pressure rise to >20 mmHg should be suspected of having AKI as a result of intra-abdominal compartment syndrome [76].

Autoimmune profile

Depending on the clinical context, clinical signs, and

urine dipstick results, patients may require specific immunological tests, including anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic

antibody (ANCA), anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), antiglomerular basement membrane antibody (anti-GBM), and complement component 3 and 4 to rule out immune-mediated diseases (i.e. vasculitis, connective tissue diseases) (Fig. 4). These investigations should be considered mandatory in patients with AKI presenting primarily with a pulmonary-renal syndrome*, haemoptysis, or haemolysis/thrombocytopenia.*Pulmonary-renal syndromes: An update for respiratory physicians [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text PDF]. Respir Med. 2011 Oct;105(10):1413-21.

Renal biopsy

Renal biopsies are rarely performed in critically ill patients, mainly due to the perceived risk of bleeding complications and general lack of therapeutic consequences.

Other laboratory tests

Depending on the clinical context, the following tests

may be indicated:

- serum creatine kinase and myoglobin (in case of

suspected rhabdomyolysis)- lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (in case of suspected

thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP))- fragmentocytes (in case of possible TTP/haemolytic

uraemic syndrome (HUS))- N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP)

and troponin (in case of suspected cardio-renal

syndrome)- serum/urine protein electrophoresis (in case of

suspected myeloma kidney)Challenges of diagnosing AKI in critically ill patients

The interpretation of additional diagnostic investigations can be challenging, too. Dipstick haematuria is not uncommon in patients with an indwelling urinary catheter and most commonly due to simple trauma.

Even more specialised tests, like autoimmune tests, have a higher risk of false-positive results in critically ill patients. For instance, infection is a frequent cause of a false-positive ANCA result [79]. Until more reliable tests are routinely used in clinical practice it is essential to interpret creatinine results and other diagnostic tests within the clinical context [80].