In this post I link to and excerpt from ADHD in Children and Youth: Part 1 – Etiology, Diagnosis, and Comorbidity – CPS Podcast from PedsCases.

The above podcast is based on ADHD in children and youth: Part 1—Etiology, diagnosis, and comorbidity [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Paediatrics & Child Health, 2018, 447–453 from The Canadian Paediatric Society.

Here are excerpts from the podcast:

This podcast gives an overview of the etiology, diagnosis, and comorbidities of ADHD in children and youth. In this episode, listeners will learn about the background and causes of ADHD, the diagnostic criteria for ADHD, the differential diagnosis for ADHD, conditions commonly comorbid with ADHD, and how to apply this knowledge to a clinical case. This podcast was created by Renée Lurie, a third-year medical student at the University of Ottawa, in collaboration with Dr. Stacey Bélanger, Dr. Mark Feldman, and Dr. Brenda Clark, of the Universities of Montreal, Toronto, and Alberta respectively.

Related Content:

- Podcast: ADHD in Children and Youth: Part 2 – Treatment – CPS Podcast

- Podcast: ADHD

- Podcast: Developmental Assessment

- Case: School difficulties in a 7-year-old female

Introduction

This is part one of a three-part series based on the 2018 CPS

Statement on Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder or ADHD. This podcast will focus on the new CPS statement, ADHD in children and youth: Part 1 – Etiology, diagnosis and comorbidity.**What follows is from the CPS statement above:

And now returning to the PedsCases ADHD Part I transcript:

Background

ADHD or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is a neurodevelopmental disorder

Not only does it affect children, 50% will continue to have symptoms into adolescence and adulthood.

Causes of ADHD

Research shows that ADHD is multifactorial, due to a combination of genetic, neurological and environmental factors. It is highly hereditary and due to multiple genes.

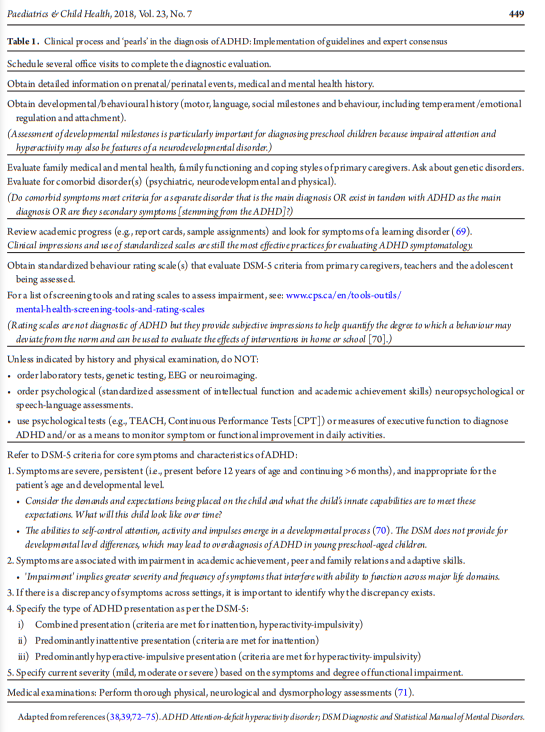

Making the diagnosis of ADHD

To assist in the diagnosis, clinicians will often use rating

scales and screening tools* such as the Conner’s Comprehensive Behavior Rating scale and the ADHD Rating Scales IV. The parents, teacher(s), and sometimes the adolescent will be asked to complete one or more these tools. Since symptoms need

to be present in multiple settings and impair everyday functioning to diagnose ADHD, gathering information from several sources is crucial.

*See Which ADHD Rating Scales Should Primary Care Physicians Use? from CHADD accessed 11-3-2020.

Clinical impressions and standardized scales are still the best ways to identify ADHD symptoms. Although one cannot make the diagnosis based on rating scales alone, these are helpful to identify the severity of symptoms and how effective certain interventions may be.

The diagnosis of ADHD is based on criteria from the DSM-5. The DSM-5 characterizes ADHD in three ways – predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive or combined inattentive-hyperactive-impulsive.

Lastly, it is important to complete a physical and neurological exam and a dysmorphology assessment is required. Unless the physical history indicates, lab tests, genetic tests, EEGs and neuroimaging are not required. Moreover, psychological testing, assessing intellectual and executive function or academic skills, and speech-language assessments are not routinely indicated.

Differential Diagnosis

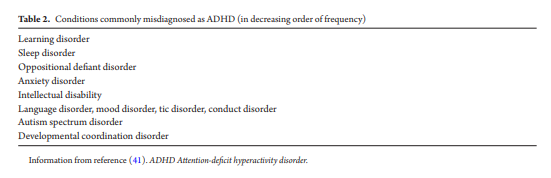

Common conditions that can be misdiagnosed as ADHD, in decreasing order of frequency, include:

1. Learning disorders

2. Sleep disorders

3. Oppositional defiant disorder

4. Anxiety disorder

5. Intellectual disability

6. Language disorder

7. Mood disorder

8. Tic disorder

9. Conduct disorder 10. Autism spectrum disorder

11. Developmental coordination disorderFor example, disruptive and aggressive behaviours, seen in oppositional defiant disorder or ODD may be mistaken for hyperactivity or impulsivity. Whereas, anxiety and depressive disorders may be mistaken for inattentiveness. Finally, conditions with frequent changes in mood, such as bipolar and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, may be misinterpreted as the combined presentation of ADHD. It is important to rule out PTSD or an adjustment disorder if there is a history of trauma or a stressor in the child’s life.

Children with intellectual disabilities or learning or language disorders may be inattentive, disconnected or disruptive in class if the school work is too difficult for them. On the opposite side of the spectrum, those with above average intellectual functioning may be inattentive if they find themselves under-challenged in the classroom. If symptoms exist only in select settings, it is important to identify why this discrepancy exists.

Finally, it is important to recognize medical conditions that may display similar symptoms to ADHD. For example, conditions that result in fatigue or pain, such as sleep apnea and inflammatory bowel disease, visual or auditory impairments, and neurological conditions that affect attention, such as epilepsy. As well, if due to a chronic health condition, a child misses a lot of school, poor school performance may be attributed to ADHD but in reality the child is unable to keep up with what is being taught in class. A medical condition can also be comorbid with ADHD and treating the condition may help diagnose ADHD.

Comorbidity

Certain disorders have a higher prevalence of ADHD than other conditions. ADHD in autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, and individuals born preterm will be discussed in part three of this series.

Another comorbidity is epilepsy.

Children with genetic conditions, such as Fragile X and Turners syndrome, have a higher occurrence of ADHD than the general population.

Neurodevelopmental and psychiatric comorbidities include disruptive behaviour disorders, such as oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder, anxiety, obsessive compulsive, mood, substance use, eating, and tic disorders.

The most common comorbid disorder associated with ADHD is a specific learning disorder, found in one-third of children with ADHD.

If [any] these comorbidities are suspected and/or if making a diagnosis is challenging, consider referring to a specialist or subspecialist in the area.