This post [my study notes] consists of resources on Excessive Daytime Sleepiness.

The following are excerpts from Resource (1) below:

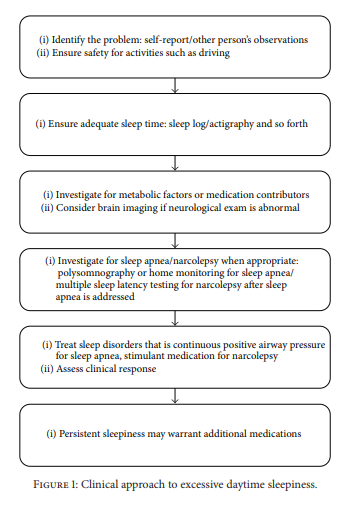

3. Clinical Approach

See Figure 1 for the general approach to clinical management. The first step is identifying EDS. The individual identifies EDS when it is creating a problem in their life such as falling asleep in inappropriate settings such as driving.

Some patients may not identify sleepiness but will identify their problem as fatigue. Fatigue is vague word and may reflect sleepiness but also reflects attributes including pain, disability, and depression.

There are many causes of EDS [1]. The first condition to identify is that of insufficient sleep. Most people need around 7–9 hours of sleep and many get less. If someone needs to wake up by an alarm clock, they are most likely getting insufficient sleep time.

Metabolic problems can also contribute to sleepiness. Patients with anemia and hypothyroidism commonly report

fatigue. A number of other metabolic disorders can produce sleepiness including hepatic and renal failure. Electrolyte abnormalities or systemic inflammation can also contribute. These conditions are generally identified on a basic medical examination and blood work.Medications are another common contributor to sleepiness; psychoactive medications are particularly problematic. Many antidepressants, anxiolytics, pain medications, and antiepileptics impair alertness. Over-the-counter medications must also be considered; antihistamines are associated with somnolence, for example. Drugs and alcohol may also contribute to sleepiness.

After these factors are addressed, sleep apnea (SA) will be one of the most common presenting conditions. Increased weight, enlarged neck circumference, and airway abnormalities may be identified in addition to a report of snoring.

The upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS)* should also be carefully considered. Even if there is no significant oxygen desaturation, or scored hypopneas, sleep may be fragmented by mild obstructive events and sleep fragmentation and

consequent daytime sleepiness results.*See Resource (2) below.

Less commonly, narcolepsy* will be responsible for sleepiness. Narcolepsy occurs in about 1 in 2000 persons. While this is rare, these patients are more likely to present to a sleep specialist. EDS is the only symptom that must be present to establish a diagnosis.

*See Resource (3) below.

Brain abnormalities can also impair alertness. Distortion of midline projecting systems by a mass lesion is notorious for producing somnolence. [And head injuries can also cause EDS.*]

*See Resource (4) below.

Many neurodegenerative conditions are associated with sleepiness. A careful neurologic examination may identify these conditions. Neuroimaging is suggested in most of these situations.

4. Measurement of Sleepiness

A simple tool that is commonly used in clinical practice is the Epworth Sleepiness Scale [3]. This is an 8-item scale that asks people to subjectively assess how likely they are to fall sleep in a variety of common situations.

Polysomnography is not useful to quantify sleepiness. However, polysomnography may be obtained for assessment of possible obstructive SA [as a cause of EDS]. . . . . If a multiple sleep latency test is going to be pursued, this must follow a conventional polysomnogram [done to first rule out Obstructive Sleep Apnea].

There are published practice parameters on the use

of neurophysiological alertness testing. The multiple sleep latency test (MSLT)* is best used for the diagnosis of narcolepsy [5]. . . . A drug screen can help ensure there is no substance contributing to daytime sleepinessSee Resource (5) below.

5. Treatment Options

Treatment options should start by ensuring that adequate sleep time is obtained. Strategic napping may also help [8]. Treatment of underlying sleep disorders such as SA with continuous positive airway pressure, for example, is essential.

A number of other simple measures may assist the subject with sleepiness. Standing up can improve alertness. Bright light is helpful, particularly with evening work. Caffeine is commonly used to enhance alertness [9]. Caffeine should be avoided beyond mid-afternoon if possible to minimize sleep disruption. Removing sedative substances is also important. Unnecessary medications that are sedating should be removed or switched to more alerting options if they are available. Some antidepressants, such as fluoxetine taken in the morning, for example, are alerting and this may represent a better choice over a sedating option such as amitriptyline. Sleeping pills have “hangover” effects that impair alertness the following day and should be avoided. Chronotherapeutics, or simply changing the timing of medication administration,

may be helpful [10].Once SA is treated, EDS is sometimes persistent. The

UARS may be a contributing factor and should be addressed as best possible. As an adjunct to the treatment of SA, modafinil can be added [11].Additional Points

Daytime sleepiness is a common presenting concern to physicians. With a careful history, the underlying cause can often be identified. Investigations, including neurophysiological tests, will identify contributing conditions, and a variety of medications are available for management, which can improve quality of life and prevent harm. New tools are under development that will better allow us to quantify sleepiness, and new medications should help facilitate more targeted treatment with fewer side effects.

Resources:

(1) A Practical Approach to Excessive Daytime Sleepiness: A Focused Review [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Can Respir J. 2016; 2016: 4215938.

(2) Treatment of upper airway resistance syndrome in adults: Where do we stand? [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Sleep Sci. 2015 Jan-Mar;8(1):42-8. doi: 10.1016/j.slsci.2015.03.001. Epub 2015 Mar 20.

The above article has been cited by 4 PubMed Central articles.

(3) Narcolepsy, Updated: Mar 26, 2019

Author: Sagarika Nallu, MD from emedicine.medscape.com

(4) . Baumann C. R., Werth E., Stocker R., Ludwig S., Bassetti C. L. Sleep-wake disturbances 6 months after traumatic brain injury: a prospective study. Brain. 2007;130(7):1873–1883. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm109.[PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

(5) Practice parameters for clinical use of the multiple sleep latency test and the maintenance of wakefulness test [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text PDF]. Sleep. 2005 Jan;28(1):113-21.

The above article has been cited by over 100 PubMed Central articles.

(2) Caffeine: sleep and daytime sleepiness [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Sleep Med Rev. 2008 Apr;12(2):153-62. Epub 2007 Oct 18.

The above article has been cited by 55 PubMed Central articles.

(3) An integrative review of sleep for nutrition professionals [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Adv Nutr. 2014 Nov 14;5(6):742-59. doi: 10.3945/an.114.006809. Print 2014 Nov.

The above article has been cited by 13 PubMed Central articles.