11-13-2021 Note to myself: Although the guideline is useful, it is very long and not entirely user-friendly. When I need to review evaluation and treatment of TIA, I recommend going to Link To And Excerpt From Transient Ischemic Attack By StatPearls With An Additional Resource From The European Stroke Organization

Posted on November 13, 2021 by Tom Wade MD.

This is because I’ve included the European Stroke Organization’s guidelines on how to determine TIA risk to decide when dual antiplatelet therapy is indicated and when monotherapy is indicated in the body of that post.

In this post, I link to and excerpt from European Stroke Organisation (ESO)

guidelines on management of transient ischaemic attack [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Eur Stroke J. 2021 Jun;6(2):V.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Abstract

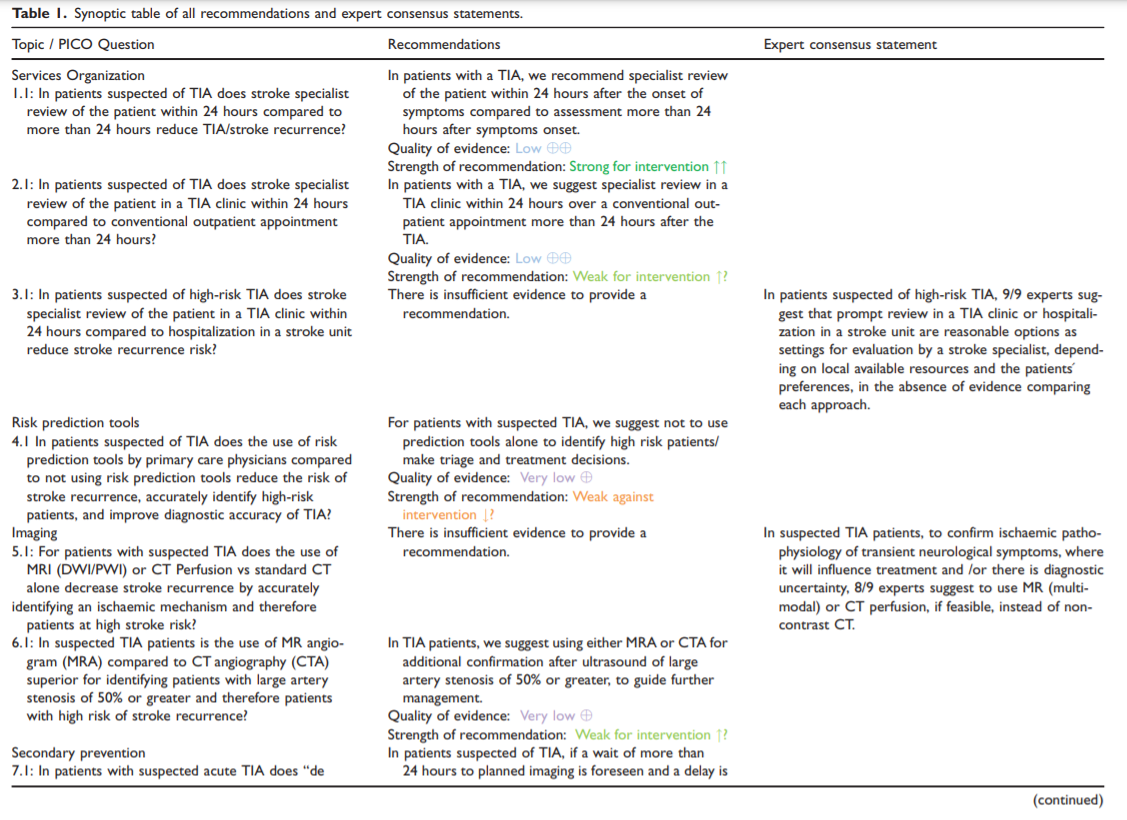

The aim of the present European Stroke Organisation Transient Ischaemic Attack (TIA) management guideline document is

to provide clinically useful evidence-based recommendations on approaches to triage, investigation and secondary prevention, particularly in the acute phase following TIA. The guidelines were prepared following the Standard Operational

Procedure for a European Stroke Organisation guideline document and according to GRADE methodology. As a basic

principle, we defined TIA clinically and pragmatically for generalisability as transient neurological symptoms, likely to be due to focal cerebral or ocular ischaemia, which last less than 24 hours. High risk TIA was defined based on clinical features in

patients seen early after their event or having other features suggesting a high early risk of stroke (e.g. ABCD2 score of 4

or greater, or weakness or speech disturbance for greater than five minutes, or recurrent events, or significant ipsilateral

large artery disease e.g. carotid stenosis, intracranial stenosis). Overall, we strongly recommend using dual antiplatelet

treatment with clopidogrel and aspirin short term, in high-risk non-cardioembolic TIA patients, with an ABCD2 score of 4

or greater, as defined in randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We further recommend specialist review within 24 hours

after the onset of TIA symptoms. We suggest review in a specialist TIA clinic rather than conventional outpatients, if

managed in an outpatient setting. We make a recommendation to use either MRA or CTA in TIA patients for additional

confirmation of large artery stenosis of 50% or greater, in order to guide further management, such as clarifying degree of

carotid stenosis detected with carotid duplex ultrasound. We make a recommendation against using prediction tools (eg

ABCD2 score) alone to identify high risk patients or to make triage and treatment decisions in suspected TIA patients as

due to limited sensitivity of the scores, those with score value of 3 or less may include significant numbers of individual

patients at risk of recurrent stroke, who require early assessment and treatment. These recommendations aim to emphasise the importance of prompt acute assessment and relevant secondary prevention. There are no data from randomisedcontrolled trials on prediction tool use and optimal imaging strategies in suspected TIA.Keywords

Transient ischaemic attack (TIA), TIA clinic, dual anti-platelet treatment (DAPT), clopidogrel, ticagrelor, aspirin,

secondary prevention, large vessel stenosis, clinical prediction tools, ABCD2Date received: 4 October 2020; accepted: 16 January 2021

Introduction

Transient ischaemic attack (TIA) and suspected TIA

are a common presentation to acute stroke services.

An increased risk of stroke following TIA is recognised, especially in the acute phase. In about a quarter of stroke patients, a TIA has preceded the stroke.1 A TIA may provide a short window of opportunity to reduce the risk of long-term morbidity and mortality.2Diagnosis of TIA can be challenging, with significant inter-rater variability.3,4 TIA definition for the purpose of these guidelines, and for generalisability across settings, is clinically diagnosed and based on symptom duration of less than 24 hours.

Early stroke specialist input can influence TIA diagnosis and subsequent management. To reduce the risk of stroke and other vascular outcomes, different treatment strategies and choice of assessment settings have been developed including TIA clinics and urgent assessment in stroke units.4–7

Major advances have been made in TIA management, including improved treatments (eg. antiplateletand lipid-lowering medications), advanced neuroimaging techniques and enhanced models of care/triage in recent years.1,10–13

Neurovascular imaging of the brain and extracranial

or intracranial vessels may identify potential high-risk

mechanisms and patterns of ischaemia, but have

limitations.12,14The aim of this guideline is to provide recommendations to guide stroke care providers to reach clinical decisions in practice when assessing patients with suspected TIA, along with investigation and management strategies to reduce the risk of long-term disability. Accurately identifying high risk patients may be helpful in triage decisions for assessment and treatment

decisions.15These guidelines focus on issues specific to early TIA management. Therefore, aspects such as carotid stenosis, investigation of a cardioembolic a etiology after a TIA or late secondary prevention measures are to be found in other ESO guidelines.*

*See European Stroke Organisation Guideline Directory.

Due to space constraints, the print version of this

guideline incorporates the abstract and the synoptic table summarizing the evidence-based recommendations and the expert opinions (Table 1). The full guideline document is available online.Methods

The guidelines for management of transient ischaemic

attacks (TIA) follow the standard operations procedure (SOP) defined by the European Stroke Organization (ESO),16 that is based on the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) system.17High risk TIA was defined based on clinical features

in patients seen early after their event and having other

features suggsting a high early risk of stroke (e.g. ABCD2 score of 4 or greater, significant large artery disease eg carotid stenosis, intracranial stenosis, weakness or speech disturbance for greater than five minutes, recurrent events).10,11,13,14,19,20Presence of infarction on imaging is also considered

as a marker of high stroke recurrence risk.13,14,20Low risk TIA was defined by absence of high risk

features (i.e. those in whom brain-tissue damage has

not been detected on diffusion-weighted imaging,

with no documented stenosis in the ipsilateral cerebral

artery, no major cardiac source of embolism, no small

vessel disease, and an ABCD2 score of less than 4).20The working group selected eight Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome (PICO) questions that were considered relevant for TIA management and treatment. These PICO questions cover issues ranging from services organization to secondary prevention of TIA.

A systematic review of literature was done to collect evidence to answer the PICO questions. This search was performed by a professional methodologist (AL). The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, SCOPUS, COCHRANE controlled trials registers. Searches were done from inception to 6 of June of 2018

In this manuscript, the analysis of each PICO question was addressed in distinct sections. Each section, includes an initial description of the available evidence followed by the ensuing recommendation. Whenever a recommendation was not possible due to the unavailability of data, an expert suggestion was made if deemed relevant.

Results

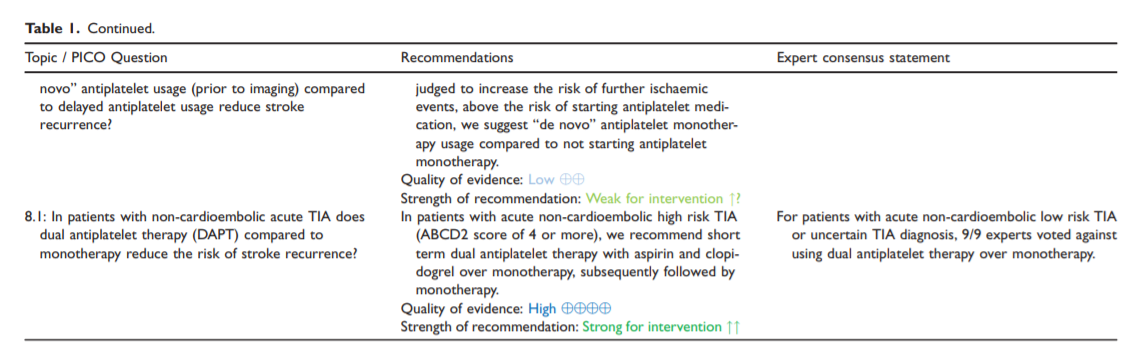

1. In patients suspected of TIA does stroke specialist review of the patient within 24 hours compared to more than 24 hours reduce TIA/stroke recurrence?

Analysis of current evidence. The pooled risk of

stroke following a TIA at 7 days is estimated to be

2.06% (95% CI, 1.83 – 2.33%) with half of the

events occurring in the first 48 hours (1.36% (95%

CI, 1.15–1.59) 95% CI 1.15–1.59).21 Therefore, timely

assessment and treatment of TIA patients could help to

prevent subsequent stroke and impact prognosis.Additional information. It is frequently difficult to

distinguish TIA from other transient neurological

attacks.22 Up to 60% of patients with suspected TIA

may have a mimic syndrome.23**23. Lee, SH, Aw, KL, McVerry, F, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic agreement in suspected TIA. Neurol Clin Pract. Epub ahead of print 13 March 2020. DOI: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000830.

Persistent neurological deficits like neglect and visual field defect can be better detected by a stroke specialist and should be evaluated as stroke, not as a TIA.24*

*24. Clissold, B, Phan, TG, Ly, J, et al. Current aspects of TIA management. J Clin Neurosci 2020; 72: 20–25.

Patients with minor, improving or fluctuating deficits may have large vessel arterial occlusions that should be evaluated immediately by stroke specialists.*

*It seems to me that this paragraph would apply to practically all patients with transient neurologic symptoms. Since many clinicians will not have stroke specialists immediately available, perhaps the primary clinician evaluating the patient (for example, an emergency physician) could, as an alternative, consult with a neuroradiologist on what imaging should be performed immediately.

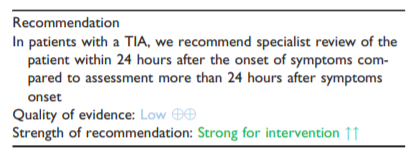

2. In patients suspected of TIA does stroke specialist review of the patient in a TIA clinic within 24 hours compared to conventional outpatient appointment more than 24 hours reduce TIA/stroke recurrence risk?

Analysis of current evidence

TIA clinics usually comprise specialist assessment, rapid completion of investigations and urgent initiation of secondary stroke prevention strategies.24 TIA clinics may allow for dedicated protected resources when there are finite clinical resources available such as protected time slots for neuro-imaging or guaranteed access to same day cardiac rhythm assessment.

TIA clinics are often designed to ensure that there is a clear pathway for patients initially seen in the emergency department for whom acute inpatient hospital admission may be avoided.

Our literature review did not identify RCTs to answer this PICO question.

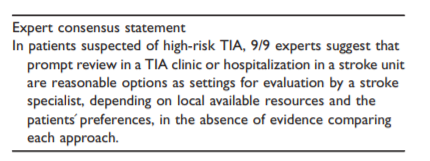

3. In patients suspected of high-risk TIA does stroke specialist review of the patient in a TIA clinic within 24 hours compared to hospitalization in a stroke unit reduce stroke recurrence risk?

Analysis of current evidence

No RCTs were identified on the systematic literature search to address this PICO question

Risk prediction tools

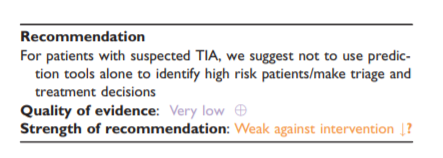

4. In patients suspected of TIA does the use of risk prediction tools by primary care physicians compared to not using risk prediction tools reduce the risk of stroke recurrence, accurately identify high-risk patients, and improve diagnostic accuracy of TIA?

Analysis of current evidence

No RCTs were identified where a prediction tool use was compared to nonuse for the outcome of prevention of stroke recurrence. No observational studies were found which compared use of a prediction score to make clinical decisions, to

without use of a score.To examine if prediction tools/clinical scores could

accurately identify high risk patient suspected of TIA

in primary care settings, studies of prediction scores

using clinical parameters were identified.Scores which included information from brain or vascular

imaging were not included as they were not designed

for use in primary care.*

*This statement is difficult for me to understand. Should a primary care physician who diagnoses TIA on clinical exam defer neuroimaging until his or her clinical diagnosis is seconded by a stroke specialist within the next 24 hours.

Additional information

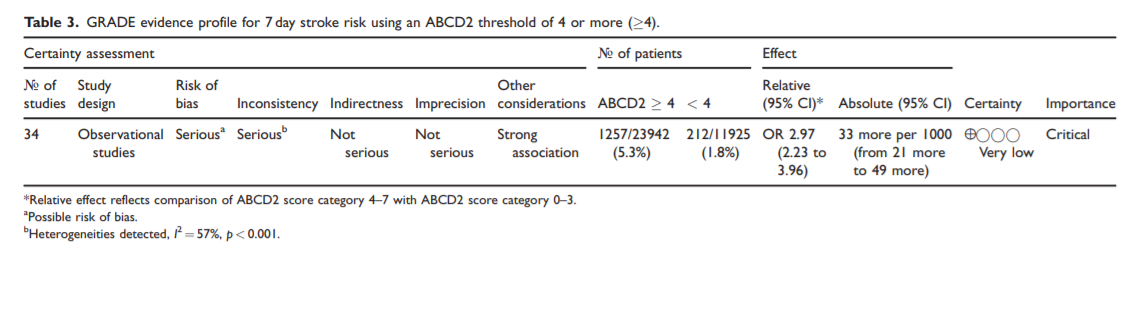

A previous meta-analysis has highlighted the low specificity of prediction tools for identifying 7 day stroke risk following TIA.34 Patients with an ABCD2 of 4 or more are categorised as highrisk based on the ABCD2 prediction tool.

Due to limited sensitivity of the scores, those with 3 or less may

include significant numbers of individual patients at high risk of recurrent stroke who require early assessment and treatment.Concern exists that use of prediction tools may

unnecessarily delay timely assessment of people at

risk of stroke, particularly those who may benefit

from a specific intervention (such as endarterectomy

or anti-coagulation) if identified early.*

*The use of prediction tools is only a problem, it seems to me, if the primary clinician (an emergency physician, for example) is not allowed to order neuroimaging or other studies (ecg monitoring or echo) until his or her clinical impression of TIA is confirmed by a stroke specialist.

Imaging

5. For patients with suspected TIA does the use of MRI (DWI/PWI) or CT Perfusion vs standard CT alone decrease stroke recurrence by accurately identifying an ischaemic mechanism and therefore patients at high stroke risk?

Analysis of current evidence

The fundamental standard for TIA diagnosis is clinically based and therefore the lack of an ischaemic neurological feature on neuroimaging does not exclude a TIA. However, agreement

on clinical diagnosis and the ischaemic pathophysiology of transient neurological symptoms, even among stroke specialists, is low.3**3. Castle, J, Mlynash, M, Lee, K, Caulfield, AF, et al. Agreement regarding diagnosis of transient ischemic attack fairly low among stroke-trained neurologists. Stroke 2010; 41: 1367–1370.

Advanced imaging can identify footprints of acute hypoperfusion changes after transient neurological symptoms. Infarction can be identified by Magnetic resonance Diffusion weighted imaging (MR DWI) and focal hypoperfusion on CT

Perfusion (CTP) or Magnetic resonance Perfusion weighted imaging (MR PWI).Diagnostic yield for identifying ischaemic changes

on standard non contrast CT imaging in TIA patients

is low (1.8–6%).38–40MR DWI imaging detected a positive DWI lesion in

34.3% (95% CI 30.5% to 38.4%) of probable TIA patients, in a univariate random-effects meta-analysis based on studies of 9078 patients, with heterogeneity between studies demonstrated by both forest plot and a high I2-statistic of 89.3%.4Amongst patients with atypical or non-focal neurological transient symptoms a positive DWI lesion rate of 23% has been reported.42

Observational studies have demonstrated that the presence of an acute positive DWI lesion is independently associated with an increased rate of early and late stroke recurrence. In the OXVASC population based study, a positive DWI was associated with an increased 10 year risk of recurrent ischaemic stroke

after an index TIA (hazard ratio [HR] 2.66, 95%CI 1.28–5.54, p

< 0.01).2,43,44Several cohort studies demonstrated that MR-PWIand/or arterial spin labelling (ASL) detect an acute

focal ischaemic lesion in between 32 and 47% of TIA

patients (7/22 (31.8%);45 21/62 (33.9%),46 14/43

(33%),47 29/90 (32.2%),48 30/64 (46.9%).49 Up to

half of the patients with an MRI PWI lesion had no

ischaemic lesion on DWI. The rate of no DWI abnormality detection in patients with PWI lesion ranged

from 10–50% (2/20 (10%),46 7/14 (50%),47 14/29

(48.3%),48 14/30 (46.7%)49)In an observational study of TIA and minor stroke,

37.3% of patients (156/418; 95%CI, 32.8–42%) had a perfusion deficit (Tmax _ 2 seconds delay) on MRI imaging, DWI abnormality was seen in 55.5% (232/418; 95% CI, 50.6–60.3) of patients, and a total of 143/418 (34.2%; 95% CI, 29.7–39%) patients had concurrent perfusion and diffusion deficits.50 One third of the acute PWI lesion progressed to infarction on follow up imaging.49Additional MR sequences such as T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo (GRE), FLAIR, T1 may help in the differential diagnosis of other cause of transient neurological symptoms that may alter patient management such as cerebral amyloid angiopathy* with transient focal neurological episodes (TFNE);

haemorrhage, tumour; inflammatory disorders; etc.51

*Please see Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy

James Kuhn; Tariq Sharman. Last Update: September 13, 2021. From StatPearls

*Please see Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

Last revised by Dr Rohit Sharma◉ on 01 Oct 2021. From Radiopaedia.

CTP detects an acute focal ischaemic lesion in 35–42% of TIA patients, and thus shows comparable rates of abnormalities to perfusion MRI. (12/34 (35.3%).40,52,53

In a series of consecutive supratentorial TIA patients 110/265 (42%) had focal perfusion abnormalities on CTP.40 Table 5.

Acute standard non-contrast computed tomography showed early ischaemic lesions in 6%, and acute/subacute magnetic resonance imaging was abnormal in 52 of the 109 cases (47.7%) where it was performed.40In an observational series of 34 acute consecutive

patients with a discharge diagnosis of possible or definite TIA, who received no revascularization therapy, standard non-contrast CT was negative in all cases, while CTP identified an ischaemic lesion in 12/34 patients (35%). In a subgroup of 17 patients with multimodal MRI, an ischaemic lesion was found in six (35%) patients using CTP versus nine (53%) on MRI

(five DWI, nine PWI).53 A stroke-unit based series of

122 consecutively admitted TIA patients found a lesion

corresponding to the transient neurological deficits in 21/110 on DWI MRI and 2/109 on standard noncontrast CT brain.38Additional information

The presence of an acute positive DWI lesion is an independent predictor of the risk of recurrent ischaemic stroke.

MRI has recognized limitations in both transient symptoms as well as clinical stroke where focal neurological symptoms persist but MRI is DWI negative (or initially negative). Delayed time from symptoms to MRI scan, type of symptoms (eg posterior circulationterritory symptoms) and technical factors relating to MR sequences, slice thickness and magnetic strength

that may influence DWI abnormality rates.54,55PWI may add on the diagnostic yield of DWI when it is negative and may be considered in patients with negative DWI or when other MRI sequences (FLAIR/GRE/MRA) disclose no alternative diagnosis.

6. In suspected TIA patients is the use of MR angiogram (MRA) compared to CT angiography (CTA) superior for identifying patients with large artery stenosis of 50% or greater and therefore patients with high risk of stroke recurrence?

Analysis of current evidence

No RCTs have been identified that directly addressed this question.

An increased risk of early recurrent stroke is recognized in patients with suspected TIA and significant symptomatic large artery disease.56,57 Prompt access to neurovascular imaging techniques to evaluate largeartery stenosis reduces stroke recurrence in TIA patients.58,59

In many centres, duplex ultrasonography (DUS) is the first step in the evaluation of carotid arteries. It has a high sensitivity and specificity to detect proximal internal carotid stenosis and it is a good cost effective screening tool.60,61 MRA or CTA may increase effectiveness slightly at disproportionately higher costs.61

In routine practice,62 Duplex ultrasonography (as first-line), computed tomographic angiography and/or magnetic resonance angiography are recommended for evaluating the extent and severity of extracranial carotid stenoses by the European Society for Vascular Surgery.62*

With continuous development of non-invasive medical imaging techniques such time-of-flight MR angiography (TOF-MRA), contrast-enhanced MR angiography (CE-MRA), multi-section computed tomography angiography (CTA), and multi-slice CT

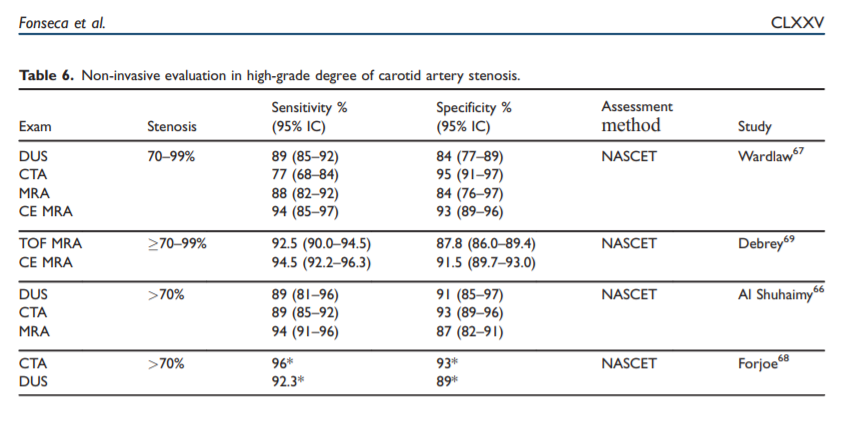

angiography (MS-CTA) the diagnostic accuracy has improved. The reported values for detection of arterial disease are variable because stenosis grading is dependent on the examination methods, post-processing techniques64–66 and the assessment method (e.g. NASCET, ECST, CCA). Meta-analysis comparing

DSA with both MRA and CTA imaging techniques showed that these techniques have a sensitivity and specificity higher than 90% for the detection of carotid stenosis 70% (Table 6).66–69However, when a large vessel has a moderate stenosis between 50–69% these non-invasive techniques havea lower sensitivity and specificity for the accurate detection of the degree of stenosis.66–71

A recent review that included previous and more contemporary studies of reported sensitivity and specificity for CTA of 81.7% and 85.6%, that may be lower than those reported for contrast-enhanced MRA.68,69

A comparative study between DUS, MRA, CTA and DSA70 and another study that compared imaging techniques with endarterectomy histological specimens, showed a better correlation with CTA than with MRA, to detect moderate carotid stenosis.71

Additional information

Additional information. Each imaging modality has

advantages and disadvantages and availability varies

across centres. Therefore, other factors may determine

the selection of the optimum testing modality for an

individual patient.To select the imaging modality technique of choice

at an individual centre, the speed of access, diagnostic

sensitivity/specificity, cost/benefit ratio, and facility for

post-processing of images needs to be considered.The reference standard for the diagnosis of intracranial stenosis and occlusion is DSA and, recently, CTA, MRA, or contrast-enhanced MRA.73

Secondary prevention

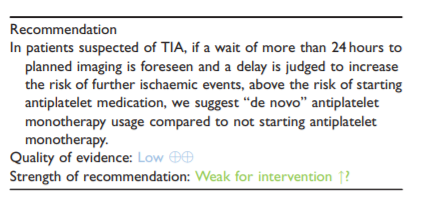

7. In patients with suspected acute TIA does “de novo”

antiplatelet usage (prior to imaging) compared to delayed antiplatelet usage reduce stroke recurrence?Analysis of current evidence and evidence-based recommendation.

Literature searches identified no RCTs comparing the outcome of patients with TIA who had been treated with antiplatelet medication only following brain imaging and those treated prior to brain imaging.

No observational studies were identified that examined specifically antiplatelet usage prior to imaging compared to a delayed usage strategy in adults with suspected acute TIA.

Due to absence of any direct RCT evidence, the working group has based suggestions on RCTs in presumed ischaemic stroke, clinical experience and knowledge of the topic.

The number of patients with suspected TIA who have

alternative diagnoses (subdural haematoma, intracerebral haemorrhage, vascular malformations, convexity SAH and superficial siderosis and microbleeds) which would be perceived as increasing the risks of starting antiplatelet therapy are probably very small. For example, the incidence of convexity SAH has been estimatedat about 5–10/per million/per year compared with a TIA incidence of at least 500/million/yr.77,78The risk of ischaemic recurrent events is highest within the period immediately after the TIA,2,79 with 2% risk by 2 days in a large international TIA registry study, and may be higher in population-based studies.80 The benefits of antiplatelet therapy are greatest (in both relative and absolute terms) within the first

24 hours following a TIA. Pooled analysis of the individual patient data from RCTs of aspirin versus control in secondary prevention after TIA or ischaemic stroke, showed the risk of recurrent ischaemic stroke was reduced by day 2 after randomisation (HR 0.44, 95% CI 0.25–0.76, p ¼ 0.0034) in patients with mild and moderately severe initial deficits.81Additional information

In patients with suspected TIA, brain imaging should be done urgently and antiplatelet treatment started without delay. If brain imaging is delayed, the available evidence suggests that the benefit of beginning antiplatelet treatment prior to

brain imaging exceeds risks associated with intracranial

haemorrhage. However, access to very early specialist

assessment and to immediate brain imaging, for patients with suspected TIA varies greatly between healthcare systems. In some, it is routine for patients to be sent to an emergency department where they can access both 24/7. However, in other health systems with limited access to imaging a delay in initiation of antiplatelet treatment while awaiting imaging risks

worsening patient outcomes.9MRI has diagnostic and prognostic utility in suspected TIA however obtaining a timely MRI in all patients may not be feasible due to technical or infrastructural reasons. Witholding an anti-platelet in the acute phase following TIA while awaiting a MRI may not be justified based on available evidence, even in the presence of microbleeds as increasingly it is reported that microbleeds are not only markers of bleeding propensity but also markers of future ischemic events.

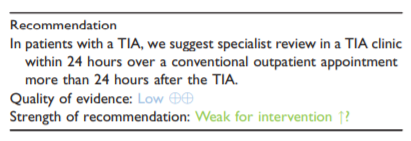

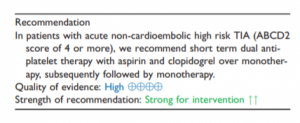

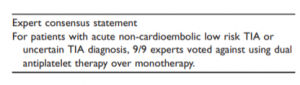

8. In patients with non-cardioembolic acute TIA does dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) compared to monotherapy reduce the risk of stroke recurrence?

Analysis of current evidence

Our literature searchidentified four RCTs10,11,19,85 which tested DAPT in patients with TIA in the acute phase and a prespecified subgroup analysis from a RCT.86 Three RCTs tested the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel versus aspirin alone and one RCT tested aspirin and ticagrelor versus aspirin in patients within 24 hours of a highrisk TIA, or minor ischaemic stroke. The subgroup analysis of the RCT tested aspirin and ticagrelor versus aspirin.86

Patients with lower risk TIAs, or where the diagnosis of TIA is uncertain, were not included in the acutephase RCTs testing dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, or aspirin and ticagrelor.

Additional information

About fifty patients need to be treated with aspirin and clopidogrel for three weeks instead of monotherapy, to avoid one stroke.

Five hundred patients treated with aspirin and clopidogrel for three weeks compared with monotherapy will cause one to have a moderate to severe extracranial bleed.

Which patients this applies to:

These results apply to patients that have high

risk TIAs according to the definition that was used

in the CHANCE and POINT trials (ABCD2 score

of 4).Patients should have brain imaging to exclude acute

intracranial bleeding, or other causes of symptoms,

prior to starting DAPT.Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel should be started as soon as possible, and ideally within the first twenty-four hours.

When starting either aspirin or clopidogrel we suggest giving a single loading dose (at least 150 mg of aspirin, and 300 mg of clopidogrel) before switching to a daily maintenance dose.

Patients with high grade carotid stenosis and planned revascularisation were excluded from POINT, CHANCE and THALES.

In patients already taking either aspirin or clopidogrel alone, we suggest continuing with the maintenance dose of that medication, and loading with the other, before continuing both medications at their maintenance dose.

Between 10 days and three weeks after starting dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) we suggest stopping one of the antiplatelet medications, and thereafter continuing the other antiplatelet as monotherapy based on local protocols and patient preference.

Discussion

The highest level of evidence was found for recommendations associated with secondary prevention treatment with dual antiplatelets. Overall, we obtained low evidence levels for recommendations regarding clinical care service organization and patient evaluation.

Most studies identified in the literature (including the RCTs) used a clinical definition of TIA. This shows that a clinical definition is still the most widely used definition in research and clinical practice, which is important for generalising the findings of these studies.

The available data show the importance of timely recognition of symptoms, assessment and commencement of secondary prevention following a TIA. Prompt assessment of patients with early initiation of secondary prevention was associated with a lower risk of stroke recurrence.

Accurately identifying high risk TIA patients may be helpful in decisions relating to initial triage for assessment and treatment. The ABCD2 score, with a threshold of 4 or more, has been used in RCTs of DAPT to identify high risk patients and has good discrimination properties when used in primary care to identify

patients at highest risk of stroke within 7 days of TIA. However, in view of the limited sensitivity of prediction scores or robust data to support their diagnostic properties, triage and treatment decisions should not be based on the use of prediction scores alone.Early access to imaging and cost of CT and MRI

varies across different health systems. Non-contrast brain CT shows ischaemic changes in less than 10% of patients. Advanced imaging such as MR (multimodal) or CT perfusion can identify acute ischaemic lesions after transient neurological symptoms and thus may accurately confirm ischaemic pathophysiology and help identify ischaemic mechanism. The overall benefit

and cost-effectiveness of different imaging approaches in suspected TIA requires further research.Our analyses of the currently available evidence

show that early initiation of DAPT with aspirin and clopidogrel in high risk non-cardioembolic TIA patients for up to 21 days reduces the risk of stroke recurrence over single antiplatelet treatment. These results apply to patients that have high risk TIAs according to the definition that was used in the CHANCE and POINT trials (ABCD2 score of 4). More studies are needed to establish if the results of these RCTs also apply to TIA patients with other features suggesting a high early risk of stroke (e.g. significant ipsilateral large artery disease e.g. carotid stenosis, intracranial stenosis, weakness or speech disturbance for greater than five minutes, recurrent events or with infarction on neuro-imaging).In clinical trials DAPT was started within 24 hours from symptoms onset in high-risk non-cardioembolic TIA (ABCD2 score of 4). The evidence base for maximal benefit-risk balance is with early and time limited (10 to 21 days) use of DAPT.

An actively recruiting RCT (CHANCE-2) seeks to answer remaining questions regarding different DAPT regimens.92

This current guideline only addressed selected issues related to

TIA management. However, it is important to highlight that TIA secondary prevention also includes medium and longer-term pharmacological and nonpharmacological measures that aim to control risk factors for late vascular events.Although prompt and targeted evaluation for symptomatic carotid stenosis is a key aspect of TIA evaluation, other investigations to determine TIA aetiology and risk factor are required, such as assessment for atrial fibrillation to guide optimal secondary prevention.*

*And evaluation of the heart with ECG and echocardiogram. See Transient Ischemic Attack. By Kiran K. Panuganti; Prasanna Tadi; Forshing Lui. From StatPearls. Last Update: September 29, 2021. The following is from this resource:

The 2009 AHA/ASA guidelines include “neuroimaging within 24 hours of symptom onset and further recommend MRI and diffusion-weighted MR imaging as preferred modalities.” A head CT preferably with a CT angiogram is recommended if an MRI cannot be performed. Brain MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging has a greater sensitivity than CT for detecting small infarcts in patients with TIA. The practitioner should assess the patient’s cervicocephalic vasculature for atherosclerotic lesions using carotid ultrasonography/transcranial Doppler ultrasonography, magnetic resonance angiography, or CT angiography. These lesions are treatable. In candidates for carotid endarterectomy, carotid imaging should be performed within 1 week of the onset of symptoms. Cardiac assessment should be done with ECG, Echocardiogram/TEE to find a cardioembolic source and the presence of patent foramen ovale, valvular disease, cardiac thrombus, and atherosclerosis. Holter monitor or more prolonged cardiac rhythm monitor in the outpatient setting is reasonable for patients with cortical infarct without any clear source of emboli, primarily to evaluate for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Routine blood tests including complete blood count (CBC), PT/INR, CMP, FBS, lipid panel, urine drug screen, and ESR should be considered.[6][7][5].

Now we resume excerpts from European Stroke Organisation (ESO)

guidelines on management of transient ischaemic attack [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Eur Stroke J. 2021 Jun;6(2):V.

Future challenges and areas that merit further research include treatment of recurrent TIA, utility of telemedicine in TIA management and TIA assessment in resource-limited settings.

Public health strategies to improve early recognition of TIA in members of the general public are also needed to optimise stroke prevention after TIA.