Be sure and also review these related resources:

- #334 IBS, Functional Dyspepsia, and Cyclic Vomiting: Disorders of Gut Brain Interaction (DGBI), By

- Transcript-The-Curbsiders-334-GutBrainIBS

- “Learn diagnostic and therapeutic management strategies for IBS, functional dyspepsia, and cyclic vomiting (aka disorders of gut brain interaction (DGBI))! It’s like three episodes in one as we run through how to individualize evaluation and management for patients with functional dyspepsia, IBS, and cyclic vomiting. Topics: scripts for counseling patients, the pathophysiology of DGBI, which diagnostic tests are necessary, pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options, and even hypnotherapy?! We’re joined again by the great Dr. Xiao Jing (Iris) Wang, (@IrisWangMD, Mayo Clinic).”

- YouTube video, Management of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Dysautonomia – Laura Pace, MD, PhD. Jul 20, 2020. Dysautonomia International.

- Dr. Laura Pace is a neurogastroenterologist from the University of Utah. She gave a great overview of gastrointestinal motility testing and how these tests may be helpful for people with dysautonomia who have gastrointestinal motility problems.

- Pancreatic Cancer

Updated: Jun 13, 2022

Author: Tomislav Dragovich, MD, PhD from emedicine.medscape.com - Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Imaging

Updated: Feb 28, 2018

Author: Mahesh Kumar Neelala Anand, MBBS, DNB, FRCR emedicine.medscape.com

In this post, I link to and excerpt from The Curbsiders‘ #340 Gallbladder Disease With Dr. Rahul Panneala, By

All that follows is from the above resource.

Transcript-The-Curbsiders-340-Gallbladder.docx-1

Help your patients navigate gallbladder disease, including asymptomatic stones, incidental polyps, and uncomplicated cholecystitis. Dr. Rahul Pannala (@RahulPannala) talks us through how to diagnose biliary colic, what imaging to order, and what to anticipate for potential post-cholecystectomy complications (eg persistent pain or diarrhea). Feel confident in sending the right patients for cholecystectomy

Show Segments

- Intro, disclaimer, guest bio

- Guest one-liner

- Case from Kashlak; Definitions

- Typical biliary pain

- Imaging for cholelithiasis

- Treatment for symptomatic gallstones

- Post-cholecystectomy diarrhea and pain

- Inpatient management of cholecystitis

- Advanced imaging- HIDA scans and MRCP

- Incidental gallbladder findings

- Outro

Gallbladder Disease Pearls

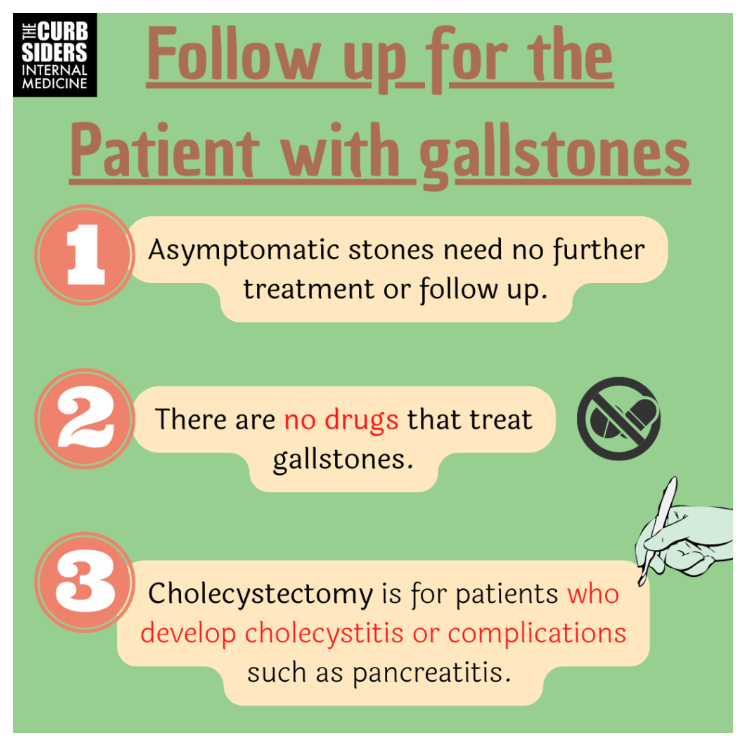

- Gallstones are common, patients with asymptomatic gallstones do not need a cholecystectomy.

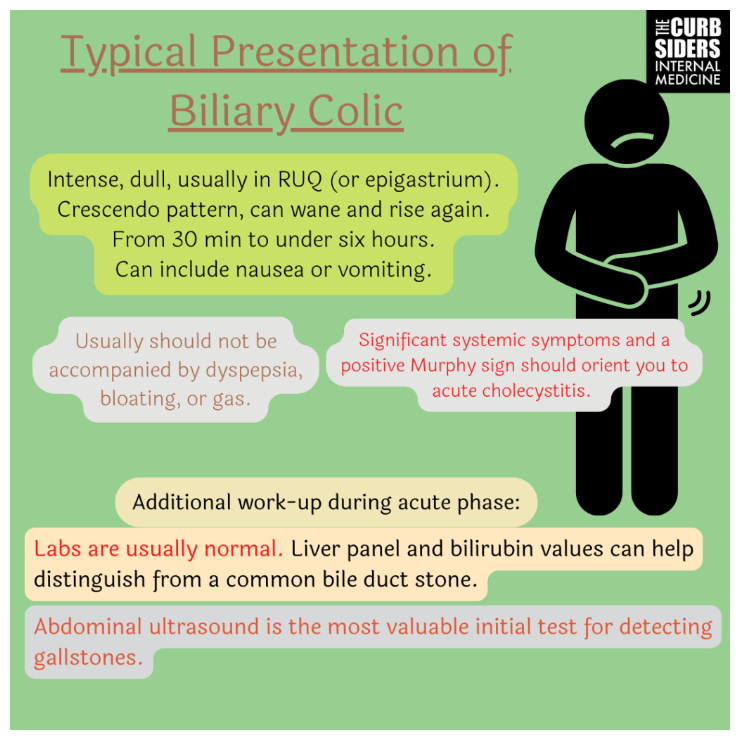

- Typical presentation of biliary pain: moderate-severe pain, which may be diffuse abdominal/epigastric or localized to the right upper quadrant and may radiate to the back. Typically pain episodes last from 30 minutes to several hours. Biliary pain classically should not include dyspepsia, bloating, or gas but is frequently associated with nausea.

- Up to 40% of patients may have continued pain after a cholecystectomy, so it is important to confirm that the abdominal pain your patient is experiencing is truly from gallstones before surgery (and not blame their functional dyspepsia on incidentally noted gallstones).

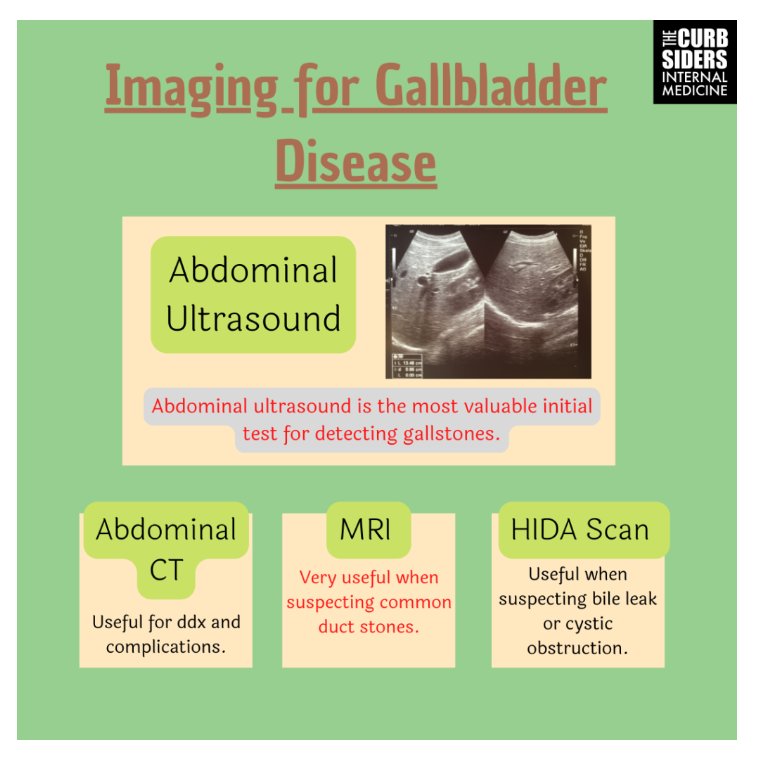

- Ultrasound is the imaging of choice for cholelithiasis.

Symptoms of biliary colic

Typical presentation of biliary pain: moderate-severe pain, typically with a crescendo pattern building over time then sometimes waning (but not resolving) then rising again. Typically these episodes last from 30 min- several hours. If you probe, often patients can describe similar (though more mild episodes) prior. Symptoms should not include dyspepsia, bloating, or gas. Nausea is common, vomiting is variable. Location may or may not be helpful- patients may describe diffuse or epigastric abdominal pain, not always classically right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Pain radiating to the back could suggest pancreatic pain or gallbladder pain.* In Dr. Pannala’s experience, if the patient is young and describing more of a dyspepsia-type symptom, cholelithiasis is unlikely to be the etiology. (Latenstein 2021)

*For information on when and how to consider pancreatic cancer testing, please see:

- Pancreatic Cancer

Updated: Jun 13, 2022

Author: Tomislav Dragovich, MD, PhD from emedicine.medscape.com - Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Imaging

Updated: Feb 28, 2018

Author: Mahesh Kumar Neelala Anand, MBBS, DNB, FRCR emedicine.medscape.com

Physical exam:

Typically the exam is normal when a patient presents to clinic after an episode of biliary colic has resolved.

If the patient is presenting in the middle of an episode of biliary colic, the physical exam is very helpful. It is important to evaluate for systemic signs to triage illness severity. The Murphy’s sign is positive when on deep palpation in the subcostal region at the midclavicular line, severe pain is elicited. A positive Murphy’s sign suggests cholecystitis. A sonographic Murphy’s sign can be very predictive as well (ultrasound probe on the gallbladder elicits maximal tenderness) (Ralls 1982).

Labs:

Labs are typically normal after an episode of biliary colic. If a patient has persistent pain or is presenting to the emergency room, liver function tests (LFTs) are typically checked. If there is LFT elevation, this could suggest more severe disease or choledocholithiasis.

Imaging for cholelithiasis

Abdominal ultrasound is the primary test that is most valuable when evaluating biliary colic (Benarroch-Gampel 2011). CT scan is not as sensitive or specific for stones/sludge in the gallbladder. CT is most helpful if the diagnosis is not clear, and can help evaluate for pancreatitis or concern for complications of gallstone disease like a perforated gallbladder (Thomas 2016).

A hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan is helpful in evaluating the patency of the cystic duct in a patient with a less classic presentation. Dr. Pannala recommends this test for evaluating acalculous cholecystitis or bile leaks (for example, a patient post-cholecystectomy who develops severe abdominal pain).

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is helpful in evaluating a common bile duct stone, depending on the pretest probability of this diagnosis. MRCP is unnecessary for a patient with normal/close to normal liver function tests who is low risk for a CBD stone. For a patient with intermediate risk for CBD stone (ie a mild elevation in bilirubin in the 2 range), an MRCP can be valuable. If a patient has a high bilirubin (ie 4) they have a high probability of a common bile duct stone, and may benefit from endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy ASGE 2019 Guideline).

Complications of Cholelithiasis

In asymptomatic patients, only around 25% will have symptoms or complications from cholelithiasis over a ten year period. Therefore, providers do not need to act on an incidental finding of gallstones. There is no need for cholecystectomy in asymptomatic patients (Sakorafas 2007).

In patients who are symptomatic, at least ⅓ will have ongoing symptoms, approximately 2% per year will have more serious complications like pancreatitis or cholecystitis (Ahmed 2000).

Treatment for Symptomatic Cholelithiasis

Cholecystectomy is the primary treatment for biliary colic. If a patient is hospitalized with uncomplicated cholecystitis, same-admission cholecystectomy is recommended (Bellows 2005). Uncomplicated cholecystitis does not need treatment with antibiotics, these should be reserved for patients with systemic inflammation or bacteremia.

Complications of Cholecystectomy

start here.