In addition to the resources below, please see the following links to Comprehensive Cancer Information From The National Cancer Institute:

In this post, I link to and excerpt from The Curbsiders‘ #342 Checkpoint Inhibitors, By

All that follows is from the above resource.

Transcript-The-Curbsiders-342-Checkpoint-Inhibitors.docx

With great power comes great immunogenicity. Learn about the ins and outs of immunotherapy–its indications, its power, and its adverse effects–in this episode with Dr. Christian Cable, hematologist/oncologist and medical educator extraordinaire. We learn a riveting history of immunotherapy and about how checkpoint inhibitors work, as well as the best practices for identifying downstream effects of checkpoint inhibitors and their immune system activation (it’s all about the -Itis!).

Show Segments

- Intro

- What is Immunotherapy?

- A History Lesson

- Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs)

- Immune Related Adverse Events (irAEs)

- Endocrine complications of checkpoint inhibitors

- Rheumatologic complications of checkpoint inhibitors

- Considerations before starting checkpoint inhibitors (and what labs to check)

- Diagnosing and Managing irAEs

- Common post-irAE questions

- New Kids on the Block: CAR-T

- Take Home Points

- Outro

Checkpoint Inhibitors and Immunotherapy Pearls

- Immunotherapy has a century-plus long history, and is based on the principle that the immune system can attack specific “bad” or “other” cells, including tumor cells.

- Immunotherapy harnesses the body’s own immune system to target cancer cells. The side effect profile is different from traditional chemotherapy, founded in the inflammation that ensues when the immune system is turned on.

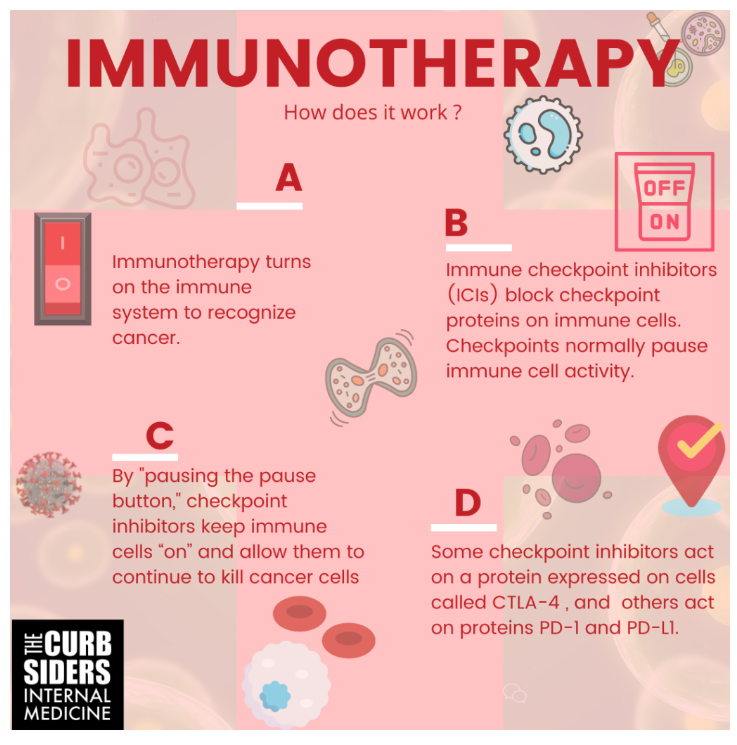

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) turn off the pause button on the immune response, and keep T-cells (and the immune response against cancer cells) active.

- There are two overall types of checkpoint inhibitors used across a variety of cancer types, ones that target CTLA-4, and ones that target PD-1/PD-L1. The most common of them are pembrolizumab and nivolumab (which target PD-1), and ipilimumab (which targets CTLA-4).

- The adverse effects from checkpoint inhibitors are byproducts of inflammation, and have parallels in autoimmune disorders of a variety of organs. They can occur at any point after initiation with checkpoint inhibitors, even years after stopping.

- Endocrine complications of checkpoint inhibitors include hypothyroidism (more common than hyperthyroidism), adrenal insufficiency, and new onset insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

- Rheumatologic complications include seronegative sicca syndrome, inflammatory arthritis (typically negative for RF, CCP, and HLA-B27), and myositis.

- Treating immune-related adverse events (irAEs) typically involves steroids (except for the endocrine complications, the treatment for which involves giving hormones to treat the underlying deficiency).

- Ensure your patients have baseline labs (TSH, FT4, AM cortisol, basic metabolic panel, glucose, liver function tests, and a complete blood count) before starting checkpoint inhibitors.

- When unsure, ask for help–first, from your oncology colleagues, but also from endocrinology and rheumatology, as your patient’s case demands.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs)

Immune checkpoints turn off the immune response (a.k.a. T-cell exhaustion). Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) block checkpoint proteins on immune cells from binding to their targets to activate this checkpoint or pause in immune cell activity. By blocking this pause (“turning off the off switch”), these checkpoint inhibitors keep T-cells “on” and allow them to continue to kill cancer cells. Some cancers have evolved to turn up checkpoint activity surrounding their tumor site to try to evade immune detection.

There are two general types of ICIs. One drug type acts on a checkpoint protein called CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4), and the others act on checkpoint proteins PD-1 and PD-L1 (programmed death 1 / programmed death ligand 1). By acting to block these interactions, ICIs keep the T-cells active, waking up the immune system against the cancer. (For more, check out a good visual abstract of PD1/PDL1 cell-based interactions on Cancer.gov). In a number of cancers, these checkpoint inhibitors perform better than traditional chemotherapy, without the same hard-to-tolerate side effects.

You may see ICIs used in a number of different cancer types, most notably prostate cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer (triple negative, primarily), colorectal cancer (ones that have high microsatellite instability), lymphomas, and melanoma. Just to name a few –and this list is evolving by the day. It may be easier to identify the cancers where it’s not going to be used than where it is.

The PD-1 targeted ICIs currently available (either commercially or in trials) are cemiplimab, pembrolizumab, and nivolumab (you will likely see pembrolizumab and nivolumab most commonly). The PD-L1 targeted ICIs are atezolizumab, avelumab, and durvalumab.

The only CTLA-4 targeted checkpoint inhibitor currently available is ipilimumab (which you will also see somewhat commonly).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are given via infusion. Infusion reactions to ICIs are quite uncommon. Patients can continue on checkpoint inhibitor therapy for years. But, in revving up the immune system, you can see more auto-immune phenomena, and more inflammation. Dr. Cable frames the possible side effects from ICIs in this context, as the byproducts of inflammation.

Immune Related Adverse Events (irAEs)

ICIs can cause many different immune-mediated conditions. These immune-related adverse events (irAEs) have indirect parallels with rheumatologic autoimmune diseases (with the exception of systemic lupus erythematosus/SLE, which interestingly does not have a parallel checkpoint-induced immune condition).

In addition to rheumatologic and endocrine complications, many organs can be affected (including the liver and the lungs). As Dr. Cable astutely points out, you can inflame anything with the checkpoint inhibitors that you can add an -itis to.

Endocrine Complications of Checkpoint Inhibitors

Hypo/Hyperthyroidism: More predominantly hypothyroidism, but hyperthyroidism can also occur (typically subclinical). Can be treated with replacement thyroid hormone or thyroid suppression, and may require longer term treatment, even after checkpoint inhibitor discontinuation.

Diabetes Mellitus: Uncommon, features rapid-onset hyperglycemia with absolute insulin deficiency, and can initially present as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in as many as 70% of cases. Because of its rapid onset, the hemoglobin A1c is of limited utility as a screening tool. Tell patients to look out for the symptoms of hyperglycemia, including polyuria and polydipsia, and to let you know if something changes. Patients may require lifelong insulin.

Adrenal Insufficiency: Rare (but slightly more common than DM). Presents with low cortisol and elevated ACTH, elevated renin, as well as typical electrolyte abnormalities. Consider imaging to rule out other adrenal disease and hemorrhage. Replace the missing hormones. (Also consider whether the patient had, prior, been getting exogenous steroids for any particular reason, such as nausea or as part of a chemotherapy regimen).

Rheumatologic Complications of Checkpoint Inhibitors

Sicca Syndrome: Sicca syndrome presents with dry eyes and dry mouth. It is related to Sjogren’s, but is not the same (and does not have the same autoantibody positivity–often negative for anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies). In Sicca syndrome, dry mouth symptoms tend to be more pronounced (Ramos-Casals 2019).

Inflammatory Arthritis: Often polyarthritis or oligoarthritis, with clinical syndromes that are very similar to their rheumatologic parallels, rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis. Inflammatory markers tend to be elevated, however these arthritides tend to be seronegative–rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP both tend to be negative (in > 90% cases), and also typically negative for HLA-B27. You will see effusions, synovitis, and erosions on imaging (see Calabrese 2018 for more).

Myositis: Very few cases of dermatomyositis, but polymyositis does occur, with sore proximal muscle weakness and diaphragmatic weakness/dysphagia, elevated creatine kinase levels (range 1000-10,000 U/L), sometimes with cardiac involvement and sometimes myasthenia gravis. (Marini 2021; Allenback 2020). Often requires high-dose steroids, and IVIG/plasma exchange in serious cases.

Considerations Before Checkpoint Inhibitor Initiation

Exclusion Criteria from Trials: Individuals with a personal history of autoimmune disease were excluded from the trials of the checkpoint inhibitors, so we don’t know much about whether checkpoint inhibitors put them at higher risk for irAEs. Consider performance status as well.

Baseline Labs To Check: Before starting ICIs, check routine baseline labs, including a basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, a glucose, a TSH and free T4, and a morning cortisol level. There is not evidence to check auto-antibody levels at baseline.

Diagnosing and Managing irAEs

Timing of irAEs: The earliest irAE to occur is typically dermatitis, with hypothyroidism to follow, with timing a few weeks to a few months. However, it’s important to remember that any of these irAEs can occur at any time, even months to years after a patient received his or her last dose of a checkpoint inhibitor. While many of the non-endocrine complications may go away with steroid treatment, the endocrine complications tend to be lifelong more often.

Ask for Help: Talk to the oncologist who is co-managing the patient with you. They can help with diagnostics and therapeutic tools you may not be as experienced with, for these novel therapeutics. But don’t forget to send your patients early to rheumatology and endocrinology.

Treatment for irAEs: First, stop the checkpoint inhibitor. Second, use the tool of the rheumatologist–steroids (can range from low dose prednisone to mega-dose solumedrol). Treat the endocrine complications as you would, normally, with thyroid, insulin, or adrenal replacement.

Common irAE-related Questions

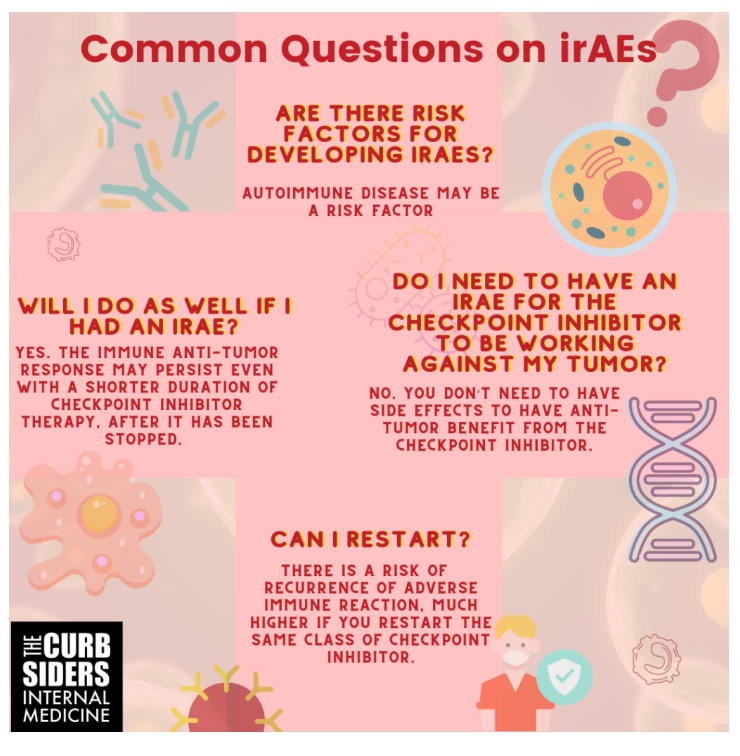

Are there risk factors for developing irAEs? Autoimmune disease may be one. There may be genetic risk factors, but we don’t understand them particularly well. And who knows, there may be some microbiome-based differences in susceptibility.

Do I need to have an irAE for the checkpoint inhibitor to be working against my tumor? You don’t need to have side effects of any sort to have the benefit from the checkpoint inhibitor. You can see tumor responses in patients without any irAEs, and treatment outcomes appear to be similar in patients with and without irAEs. The only exception to this appears to be in melanoma, where the presence of vitiligo after ICI initiation appears to correlate with improvement in melanoma. Melanoma-associated vitiligo can occur in patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors, and appears to correlate with higher survival rates in metastatic melanoma.

Will I do as well if I had an irAE? Patients with immune complications who were taken off checkpoint inhibitors did just as well as patients who continued, suggesting that the immune, anti-tumor response, may persist beyond when patients are on the medication and may provide similar benefits even with shorter duration.

Can I restart ICI therapy after an irAE? Many patients will wonder whether or not they can restart checkpoint inhibitors after an immune related adverse event. There’s an approximately 5% risk of having a recurrence of immune symptoms, if you switch classes from a PD1 inhibitor to CTLA4 inhibitor. If you stay in-class, there’s an approximately 50% chance of recurrence, so oncologists prefer not to restart (Haanen, 2020).

For more commonly asked questions, and the latest answers, check out this phenomenal 2018 NEJM review.

New Kids on the Block: CAR T-cells

Keep an eye out for more about chimeric antigen receptor T-cells*, which are cells from a patient’s body that are edited to target a cancer cell. These CAR T-cells can cause cytokine release syndrome, a severe inflammatory syndrome, but they can also cure certain lymphomas and leukemias.

*Please see the following links to Comprehensive Cancer Information From The National Cancer Institute:

Take Home Points

- You will be seeing checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) more and more in the coming years.

- The indications for ICIs are growing, in both blood and solid tumors.

- The treatment effects and side effects of ICIs are two sides of the same coin–they are both the byproducts of the revving up of the immune system, which can affect most organs and systems.