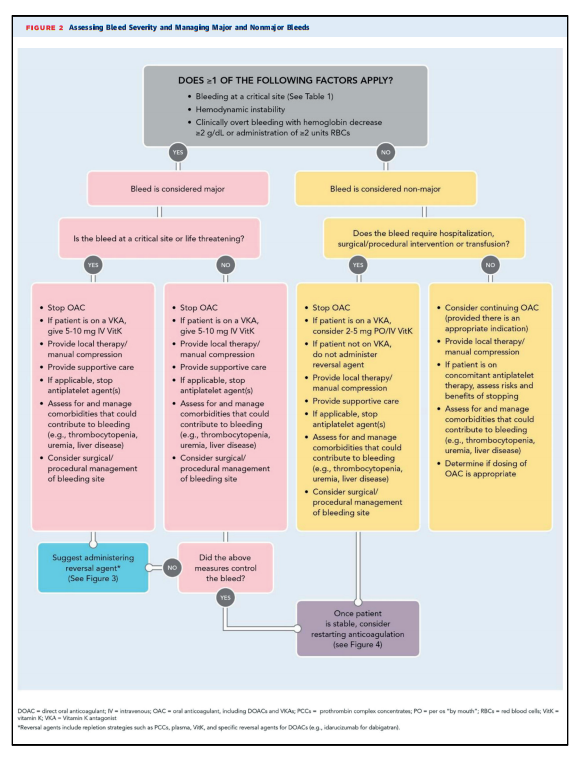

5.1. Assessing Bleed Severity

[The usual measures to assess and management of bleeding severity apply.]

e. Clinicians should be mindful of comorbidities and concomitant treatments that could also contribute to bleeding or alter its management (e.g., antiplatelet therapy, thrombocytopenia, uremia, or liver disease) and manage them as appropriate.

5.2. Defining Bleed Severity

If greater than or equal to 1 of the following factors apply, the bleed is classified as major:

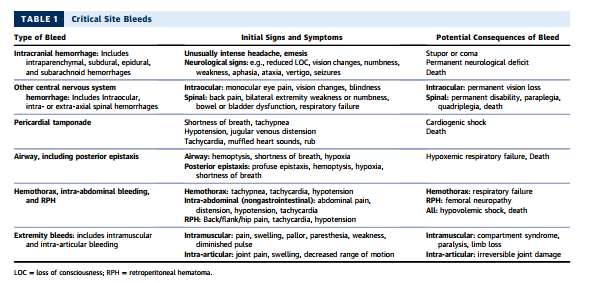

Bleeding in a Critical Site

Critical site bleeds are considered bleeds that compromise the organ’s function. Intracranial hemorrhage and other central nervous system bleeds (e.g., intraocular, spinal) and thoracic, intra-abdominal, retroperitoneal, intraarticular, and intramuscular bleeds are considered critical as they may cause severe disability and require surgical procedures for hemostasis. Intraluminal gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is not considered a critical site bleed; however, it can result in hemodynamic compromise. A list of critical bleeding locations can be found in here in Table 1.

Hemodynamic Instability

An increased heart rate may be a first sign of hemodynamic instability due to blood loss. Furthermore, a systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg, a decrease in systolic blood pressure >40 mm Hg (11), or orthostatic blood pressure changes (systolic blood pressure drop greater than or equal to 20 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure drop greater than or equal to 10 mm Hg upon standing) can indicate hemodynamic instability. However, noninvasively measured blood pressure may not always reflect intra-arterial pressure. Continuous invasive measurement of mean arterial pressure is considered superior for assessment, and a value <65 mm Hg serves as a cut-off for hemodynamic instability (11). In addition to clinical signs, surrogate markers for organ perfusion (including urine output <0.5 mL/kg/h) can be used to evaluate for hemodynamic instability (11).

Overt Bleeding With Hemoglobin Drop greater than or equal to 2 g/dL or Administration of greater than or equal to 2 U of Packed RBCs

Bleeding events causing a hemoglobin drop greater than or equal to 2g/dL or requiring transfusion of greater than or equal to 2 U of RBCs have been associated with a significantly increased mortality risk (12,13). Patients with cardiovascular disease, defined as a history of angina, myocardial infarction, heart failure, or peripheral artery disease, have an increased risk of mortality associated with a hemoglobin drop during their hospitalization (13,14). Patients who present with an acute bleed and no prior records will often have no reference hemoglobin value, and it should be kept in mind that a preresuscitation hemoglobin may be artificially high due to hemoconcentration. If a patient does not meet criteria for a major bleed (i.e., bleeding is not occurring at a critical site [see Table 1 above], the patient is hemodynamically stable and there is no clinically overt bleeding that has led to a hemoglobin decrease greater than or equal to 2 g/dL or required greater than or equal to 2 U of packed RBCs), we have classified this as a nonmajor bleeding event for this decision pathway.