In this post I link to and excerpt from Emergency Medicine Cases‘ ECG Cases 11: LBBB and Occlusion MI. Written by Jesse McLaren; Peer Reviewed and edited by Anton Helman, July 2020.

All that follows is from Dr. McLaren’s post.

In this ECG Cases blog we look at 5 patients with potentially ischemic symptoms and LBBB. Which required cath lab activation?

LBBB + occlusion MI

The left bundle branch provides rapid conduction via anterior and posterior fascicles. If it is blocked, conduction remains rapid through the right ventricle but is delayed across the left ventricle. So depolarization is prolonged (QRS>120) and leftward: anterior leads have deep/broad S waves, and lateral leads have slurred or notched R waves. In addition, the initial septal depolarization is reversed and spreads from right to left, resulting in small/no R waves in anterior leads and disappearance of “septal Q waves” in the lateral leads. Like other forms of abnormal depolarization LBBB produces repolarization abnormalities, and the discordant ST elevation and ST depression have caused a dilemma for the STEMI paradigm.

As a review summarized, “not only is the ECG diagnosis of AMI difficult due to ‘masking’ of characteristic ECG changes by altered ventricular depolarization, but these patients may be at higher risk for AMI, congestive heart failure, and death compared with patients without BBB.”[1] The first guidelines treated all patients with ischemic symptoms and LBBB as STEMI, based on early trials. Then the guidelines shifted consider “new LBBB” as STEMI equivalents, based on the assumption it takes a large anterior infarct to block both left fascicles. But most LBBB are not caused by acute ischemia but by chronic heart disease, which is a risk factor for ACS but not an automatic indication for reperfusion therapy. Patients presenting to the ED with ischemic symptoms have similar rates of MI whether they have new LBBB, old LBBB or no LBBB [2]. Treating “new LBBB” as STEMIs led to unnecessary interventions, so this indication was removed from the 2013 AHA guidelines. But this leads to the opposite problem: “the guidelines fail to recognize that some patients with suspected ischemia and LBBB do have STEMI, and denying reperfusion therapy could be fatal.”[3]

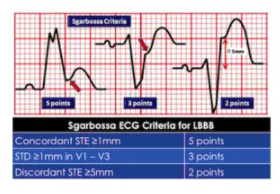

Sgarbossa first identified criteria that can identify AMI in the presence of LBBB. Since LBBB normally produces discordant STE and STD, acute ischemia can be identified by concordant STE, concordant STD anteriorly, or disproportionately discordant STE >5mm[4]:

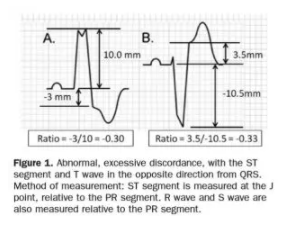

STEMI describes ST elevation in two contiguous leads, but Sgarbossa identified criteria for acute reperfusion that included concordant STE elevation or depression in one lead. But the criteria was based on enzyme-diagnosed AMI, had a complicated scoring system, and had inadequate sensitivity and specificity (in part because the criteria for disproportionate STE was based on an absolute value regardless of the size of the preceding QRS). Smith studied angiographically-confirmed culprit lesions and identified ECG criteria that can predict occlusion MI, shifting away from the STEMI paradigm and adding diagnostic accuracy to the Sgarbossa criteria. The Smith-modified Sgarbossa criteriareplaced the absolute discordance of >5mm with a relative discordance of ST/S<-0.25 (i.e. amplitude of STE greater than 25% of the amplitude of the preceding S wave), and also included any excessive discordance (either STE >30% the preceding S wave, or STD>30% preceding R wave ) in any lead [5].

The shift from STEMI to OMI (occlusion MI) includes examining ST changes (both elevation and depression) relative to the preceding QRS and in context of the patient’s symptoms. As the validation study discovered, “we found that the modified Sgarbossa criteria performed similarly well using a proportionality cutoff of -0.20 or -0.25. As expected, however, the cutoff of -0.20 produced slightly higher sensitivity than the cutoff of -0.25 (84% vs 80%) and slightly lower specificity (94% vs 99%). Thus, the decision to use -0.20 or -0.25 as the proportional discordance is not absolute but rather depends on the physician’s pretest probability and clinical context. The ECG should always be used in clinical context, as diagnostic ST elevation is frequently absent in ACO even in normal conduction (ie, no bundle branch block).”[6] Cai (cited below) proposed an algorithm that takes into account the Sgarbossa/Smith criteria, but that starts with the patient’s clinical status. As with refractory ischemia or hemodynamically unstable patients with normal conduction, the 2017 European guidelines emphasize that “patients with a clinical suspicion of ongoing myocardial ischaemia and LBBB should be managed in a way similar to STEMI patients, regardless of whether the LBBB is previously known…Suspicion of ongoing myocardial ischaemia is an indication for a primary PCI strategy even in patients without diagnostic ST-segment elevation.”[7]

Five patients presented with potentially ischemic symptoms. Which required cath lab activation?

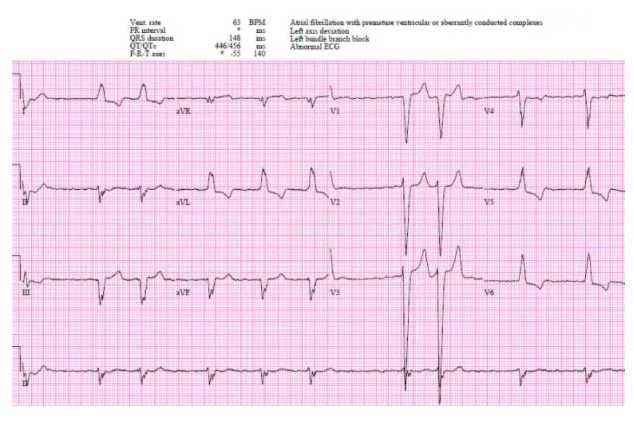

Patient 1: 90y/o history CAD, old LBBB with VT arrest, cardioverted by EMS

Patient 1: appropriate cath lab activation but no occlusion MI

AF with LBBB, no Sgarbossa/Smith criteria but high-pretest probability patient with hemodynamic instability. Cath lab activated: no acute coronary occlusion.