In this post, I link to and excerpt from A Neurologist’s Practical Approach to Cognitive Impairment [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Semin Neurol. 2021 Dec;41(6):686-698. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1726354. Epub 2021 Nov 26.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Glossary

AD Alzheimer’s disease

agPPA Agrammatic PPA

ALS Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

AOS Apraxia of speech

CBD Corticobasal degeneration

CBS Corticobasal syndrome

CSF Cerebrospinal fluid

bvFTD Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia

EOAD Early onset Alzheimer’s disease

FTD Frontotemporal dementia

HSP Hereditary spastic paraplegia

LATE Limbic-predominant age-related TDP43 encephalopathy

LBD Lewy body dementia

lvPPA Logopenic variant PPA

MCI Mild cognitive impairment

MMSE Mini-mental Status Examination

MoCA Montreal Cognitive Assessment

MSA Multiple system atrophy

NPH Normal pressure hydrocephalus

PCA Posterior cortical atrophy

PD Parkinson’s disease

PPA Primary progressive aphasia

PSP Progressive supranuclear palsy

RBD REM sleep behavior disorder

RPD Rapidly progressive dementia

SCA Spinocerebellar ataxia

STMS Kokmen Short Test of Mental Status

svPPA Semantic variant PPA

TGA Transient global amnesiaAbstract

The global prevalence of dementia is expected to triple by the year 2050. This impending health care crisis has led to new heights of public awareness and general concern regarding cognitive impairment. Subsequently, clinicians are seeing more and more people presenting with cognitive concerns. It is important that clinicians meet these concerns with a strategy promoting accurate diagnoses. We have diagramed and described a practical approach to cognitive impairment. Through an algorithmic approach, we determine the presence and severity of cognitive impairment, systematically evaluate domains of function, and use this information to determine the next steps in evaluation. We also discuss how to proceed when cognitive impairment is associated with motor abnormalities or rapid progression.

Introduction

Dementia is diagnosed in patients with cognitive/behavioral symptoms that impair normal function and represent a decline from one’s previous level of function.1

AD is the most common cause of dementia.3 Data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordination Center database shows that the current AD clinical diagnostic criteria have a sensitivity of 71-87%, but specificity of only 44-71%.4 Cognitive impairment may be diagnosed as AD when alternative pathology is causing a patient’s symptoms. . . . Neuropathological studies have demonstrated a high co-occurrence of AD with other pathologies, such as lewy bodies,5–7 vascular changes,8,9 and TDP43.10 Correct identification of concurrent pathologies leads to better patient counseling and more effective treatment strategies.

Through an algorithmic approach, we first determine the presence and severity of cognitive impairment then which domains are involved and how to proceed when each domain is predominantly affected. We also address when there is cognitive impairment with motor abnormalities and lastly, when cognitive decline is rapidly progressive.

Determining the Presence/Degree of Cognitive Impairment

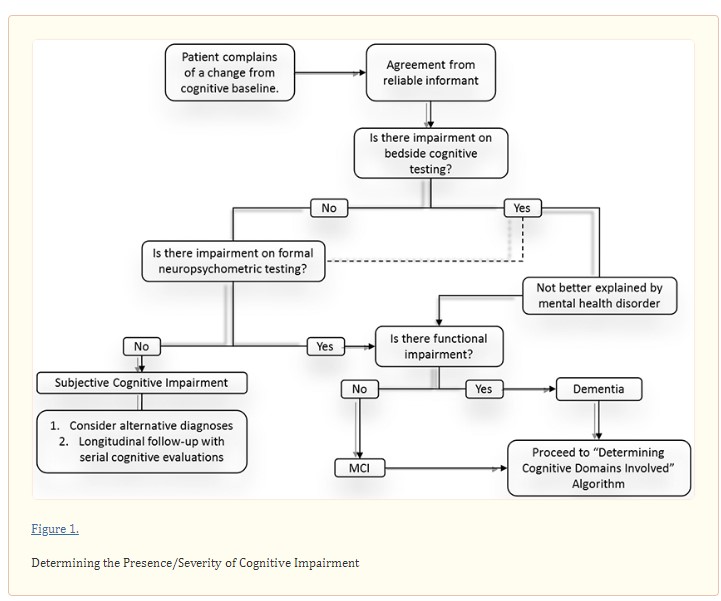

Direct interview of the patient and a reliable informant is critical to establish whether cognitive complaints represent meaningful cognitive impairment and to grade the severity of impairment (if present) early in the clinical assessment (Figure 1). Whenever possible, the initial clinical assessment should include caregivers or close friends who can clarify the trajectory of cognitive change, referencing baseline function.

In addition to history, cognitive complaints should be assessed using a validated short bedside cognitive screening test, such as the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE),11 Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA),12 Kokmen Short Test of Mental Status (STMS)13 and others. The sensitivity of these tests to identify mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is 18% for the MMSE, but much higher for the MoCA and STMS.12,14 Formal neuropsychometric testing should be considered when clinical suspicion remains high despite normal performance on cognitive screening tests. If neuropsychometric testing reveals no abnormalities, then clinicians should consider alternative diagnoses and monitor patients longitudinally. Even if short cognitive testing reveals an abnormality, neuropsychometric testing may be appropriate to characterize cognitive strengths and weaknesses.

Once cognitive impairment is objectively quantified on validated bedside testing and/or neuropsychometric testing, one should assess the severity of impairment. The diagnosis of dementia requires that deficits interfere with a patient’s independent functioning. Accordingly, the assessment should inquire about the patient’s ability to perform tasks, such as driving without getting lost, managing personal finances, and supervising medications. A diagnosis of MCI is made when cognitive impairment exists without functional impairment. MCI is present in 6.7% of individuals from 60-64 years of age,15 with prevalence increasing to 25.2% in individuals from 80-84 years of age. 15

Dementia may be mistaken for delirium. Major features that differentiate delirium from dementia include disturbances of attention/consciousness over a short time. Delirium may be provoked by infections, medications/drug abuse, metabolic derangement, and/or a disrupted sleep-wake cycle. While delirium is not a progressive disorder, demented individuals carry a greater risk of experiencing superimposed delirium. Mental health disorders may also be mistaken for dementia. Individuals with inadequately controlled depression often perform poorly on bedside cognitive tests leading clinicians to incorrectly suspect dementia. This highlights the importance of coupling cognitive testing with validated mood disorder screens, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), Beck Depression Inventory, generalized anxiety disorder 7-item (GAD-7) and others. For a diagnosis of dementia, symptoms must not be better explained by delirium or a major psychiatric disorder.16

Identifying Impaired Cognitive Domain(s)

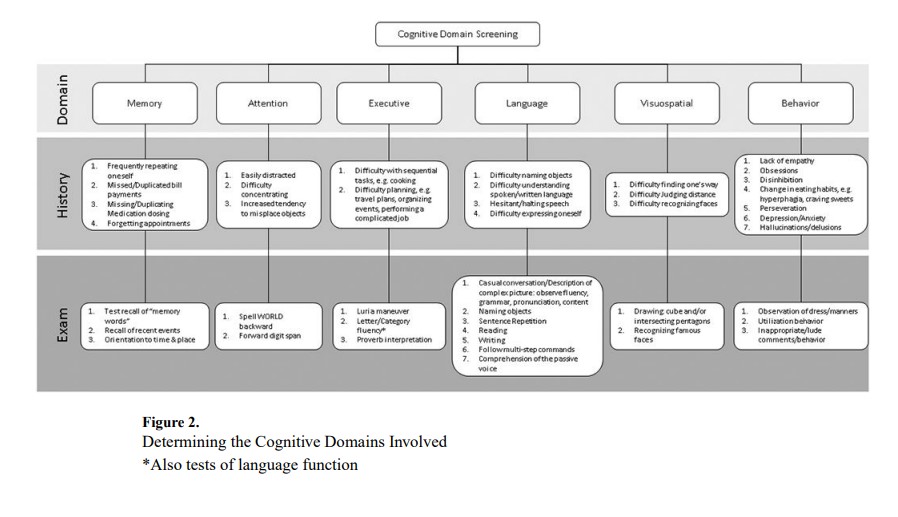

Recognizing the pattern of cognitive domains involved is key to the accurate etiological diagnosis of cognitive impairment. Figure 2 diagrams features that may be exhibited by patients with impairment in different cognitive domains.

Approach to Patients with a Predominantly Amnestic Syndrome

Memory is the most common complaint in our Behavioral Neurology clinic, yet evaluation frequently reveals impairment of other cognitive domains, such as attention. Elements suggesting actual memory impairment include an increased tendency to repeat questions and forget appointments and/or bill payments. Bedside cognitive testing is useful to identify memory impairment. Testing may reveal impairment in a non-memory domain that the patient perceives as a memory problem. Formal neuropsychometric testing confirms which specific cognitive domains are impaired and characterizes memory impairment. For instance, rapid forgetting may be demonstrated by the inability to recall or recognize memorized words. Rapid forgetting localizes to the hippocampus and is characteristic of AD.

When evaluating a patient with predominant memory impairment, it may be tempting to attribute symptoms to AD. However, consideration of a patient’s age and the temporal profile of symptoms increases one’s sensitivity to alternative etiologies that may have different treatment approaches compared to AD. Figure 3 provides a useful algorithm for approaching patients with predominant memory impairment. In patients whose memory loss is transient or episodic, one must consider transient global amnesia (TGA). Electroencephalogram (EEG) may differentiate TGA from transient epileptic amnesia (TEA).17 Clinicians should look for stroke by brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with particular attention to hippocampal and thalamic regions. When EEG and MRI are normal, one should consider associations such as migraine, medications (e.g. alcohol), and head injury as well as other etiologies listed later in this section.

Symptoms of memory loss that develop over days to weeks should prompt evaluation for toxic, metabolic, and nutritional deficiencies. We recommend measuring Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) and methylmalonic acid in all patients. Vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency may result in Wernicke’s encephalopathy, which is characterized by the emergence of encephalopathy, ataxia, and/or ophthalmoplegia in patients with nutritional deficiency. Even subtle symptoms should prompt inquiry about nutritional status, and specific risk factors for malabsorption, including alcohol use and gastrointestinal surgeries, e.g. gastric bypass. Clinicians should measure vitamin B1 levels and other nutrition-related labs when a nutritional deficiency is suspected. Hospitalized patients may be at particularly high risk of thiamine deficiency due to a preponderance of risk factors, including poor nutritional intake, increased metabolic demand, resuscitation with glucose-containing fluids and medical conditions that impair thiamine absorption from dietary sources.18–21 If acute thiamine deficiency is suspected, it is imperative that patients receive high doses of parenteral (not oral) thiamine to reverse the suspected brain-thiamine deficit and reduce the risk of substantial morbidity (including Korsakoff’s dementia) and death. Although the minimally-sufficient dose of thiamine required to correct deficiencies is unknown, doses of parenteral thiamine in excess of 200 mg are commonly recommended to rapidly reverse brain-thiamine deficiency.22–26

Chronic memory loss over months to years suggests a neurodegenerative process. Chronic progressive memory loss in those 65-80 years old is classic for late-onset symptomatic AD (LOAD). Symptom onset after the age of 80 years may suggest limbic-predominant AD27 or limbic-predominant age-related TDP43 encephalopathy (LATE).28 To date, treatment approaches for limbic-predominant AD and LATE do not differ significantly, but they may remain in the MCI stage for many years.

Early-onset AD (EOAD) is defined as symptom onset prior to the age of 65 years. Alternative etiologies may also present at younger ages. Prominent behavioral symptoms, such as loss of empathy, disinhibition, hyperphagia, support a diagnosis of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) while lewy body dementia (LBD) should be considered in the presence of associated symptoms, such as parkinsonism, REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), cognitive fluctuations, hallucinations, and/or complex visual hallucinations.29

Approach to Patients with Predominantly Attention/Executive Impairment

Individuals with impaired attention may report distractibility or difficulty concentrating. This often manifests as misplacing objects, such as keys, or forgetting where one has parked their car. Attentional deficits are often inconsistent and may vary with the time of day or state-dependent factors, e.g. sleepiness, medication exposure, etc. Bedside tasks such as spelling WORLD backward or repeating a sequence of numbers are good methods for testing attention because they require relatively little input from other cognitive domains. Other tasks such as subtracting serial 7’s or repeating number sequences in reverse order rely more on other cognitive domains, e.g. memory and executive function. When attention is impaired, one should consider the following diagnoses: Parkinson’s disease, small vessel disease, and delirium.

Executive function may be difficult to isolate given its involvement in nearly all cognitive tasks. Patients with executive dysfunction have difficulty performing sequential tasks, such as cooking. Patients often struggle with planning activities and performing complicated tasks at work. Useful bedside techniques for the assessment of executive function include copying the Luria maneuver (fist – side – palm), letter/category fluency, and proverb interpretation. Cognitively normal individuals can typically name at least 15 words that begin with a specific letter within one minute. Categorical fluency may be assessed by having patients name animals in one minute. Twenty animals is considered normal in most adults, while 15 is low average, and <10 impaired.30 Proverb interpretation is tested by asking patients to interpret the meaning of culturally-specific idioms, such as “Don’t cry over spilled milk” or “People in glass houses should not throw stones.” Neuropsychometric testing may show difficulty in the Trails B test. In our experience, executive impairment can be seen in EOAD, with preservation of memory, and may be mistaken as a primary mental health disorder. FDG-PET and/or cerebrospinal (CSF) AD biomarkers can differentiate between these conditions.31

Executive function may be difficult to isolate given its involvement in nearly all cognitive tasks. Patients with executive dysfunction have difficulty performing sequential tasks, such as cooking. Patients often struggle with planning activities and performing complicated tasks at work. Useful bedside techniques for the assessment of executive function include copying the Luria maneuver (fist – side – palm), letter/category fluency, and proverb interpretation. Cognitively normal individuals can typically name at least 15 words that begin with a specific letter within one minute. Categorical fluency may be assessed by having patients name animals in one minute. Twenty animals is considered normal in most adults, while 15 is low average, and <10 impaired.30 Proverb interpretation is tested by asking patients to interpret the meaning of culturally-specific idioms, such as “Don’t cry over spilled milk” or “People in glass houses should not throw stones.” Neuropsychometric testing may show difficulty in the Trails B test. In our experience, executive impairment can be seen in EOAD, with preservation of memory, and may be mistaken as a primary mental health disorder. FDG-PET and/or cerebrospinal (CSF) AD biomarkers can differentiate between these conditions.31

Approach to Patients with Predominantly Language Impairment

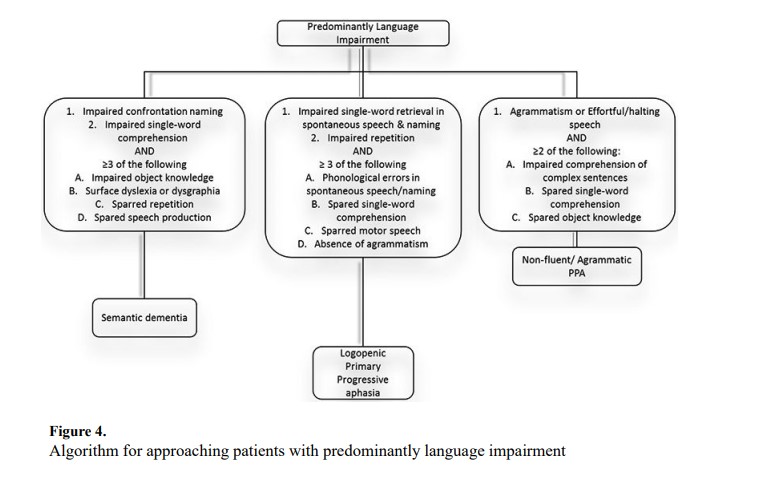

Language impairment may manifest in varying degrees from overt aphasia, following a large cortical stroke, to more subtle deficiencies of language, such as hesitant/halting speech. A reliable informant may be very informative when assessing whether subtle findings represent a departure from the patient’s baseline. Additionally, the increased availability of audio/video recordings on mobile devices gives clinicians the opportunity to hear the patient’s premorbid language function. One should assess a patient’s ability to name objects, express themself, understand spoken and written language, and the fluidity of spontaneous speech. Figure 4 illustrates our approach to evaluate the language domain.

When evaluating the patient with language impairment, acute symptom onset should prompt evaluation for stroke and seizures. Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is characterized by chronic progressive language impairment. PPA is a phenomenological diagnosis and not specific to one pathology. For this, clinicians must differentiate between the three PPA subtypes.

Semantic variant PPA (svPPA), sometimes referred to as semantic dementia, is a subtype of FTD. Patients with svPPA have difficulty understanding word meanings. Patients may have impaired object knowledge, which may be detected by various cognitive tasks, such as detecting the “odd-one-out” in a group of objects or pictures.32 Patients with svPPA often have surface dyslexia (tendency to phonetically pronounce a word, e.g. colonel pronounced as “call-on-ell”) with spared repetition and speech production.

Logopenic variant PPA (lvPPA) is an atypical variant of AD. Characteristically, patients with lvPPA have an immediate memory problem that disrupts the phonological loop, which can be evaluated with sentence repetition.33 Even on short tests, they may have difficulty remembering words and repeat short sentences such as “No ifs ands or buts.” Patients have difficulty with single-word retrieval. In casual conversation, subtle impairment may appear as merely thoughtful word choices. Asking patients to describe objects or complex pictures may make abnormalities more apparent. Patients with lvPPA make phonological errors, but single word comprehension and motor speech is spared.32

Non-fluent or agrammatic PPA (agPPA) is subtype of FTD. Patients with agPPA may present with effortful/halting speech and impaired comprehension of complex sentences. Sentences may be telegraphic, e.g. “I go work Monday,” while single word comprehension and object knowledge are spared.32

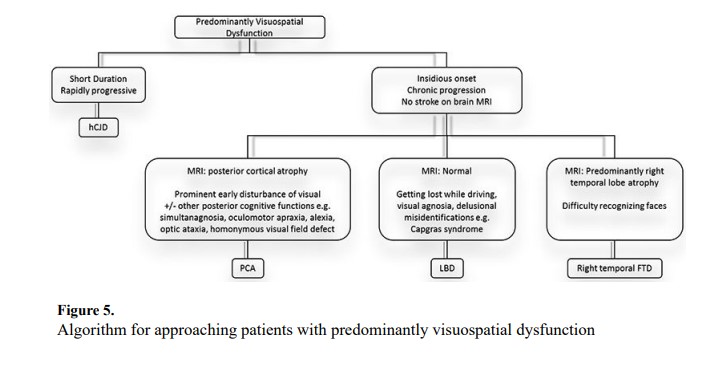

Approach to Patients with Predominantly Visuospatial Dysfunction

Patients with visuospatial dysfunction often present to a neurologist after ophthalmological assessment reveals no abnormalities. Patients with acute symptom onset should undergo immediate evaluation for stroke and other vascular pathology. Insidious symptom onset with gradual progression suggests neurodegenerative disease. Figure 5 diagrams an approach to patients with predominantly visuospatial dysfunction.

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) is an atypical form of AD though other pathologies may result in the PCA phenotype.34 Common symptoms include space perception deficits, simultanagnosia, oculomotor apraxia, optic ataxia, alexia, and visual field deficits.35 Although not included in our algorithm, a new classification of PCA-plus indicates when individuals have additional symptoms consistent with other neurodegenerative syndromes. The PCA-plus designations include PCA-LBD, PCA-corticobasal syndrome (PCA-CBS), PCA-AD, and PCA-prion.35 Patients with right more than left temporal lobe atrophy may have difficulty with facial recognition. This is a subtype of right temporal lobe FTD caused by TDP43 pathology, but when damage is greater on the right, signs and symptoms predominant in the visuospatial realm.36

LBD may present with a different variety of visuospatial dysfunction including visual agnosia and delusional misrepresentations, such as Capgras syndrome (the belief that a previously known person has been replaced by an imposter).37–38 Additional symptoms including autonomic dysfunction, RBD, and parkinsonism may help to confirm the diagnosis.29 The Heidenhain variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease is characterized by rapidly progressive visual impairment.39 Symptoms may include disturbed perception of colors/structures, hallucinations, cortical blindness, and visual anosognosia.40

Approach to Patients with Predominantly Behavioral/Frontal Symptoms

Overt behavioral signs and symptoms may include overt obsessions, disinhibition, hallucinations, and others, while more subtle signs may include a lack of empathy, craving sweets, and anxiety/depression. Useful observations during a clinical encounter include abnormal dress/manners, perseveration, and inappropriate/lude comments or behaviors. Utilization behavior is one feature that may be elicited by placing a tools (e.g. ink pen or sunglasses), in front of the patient. Patients with utilization behavior will inevitably attempt to use the object.

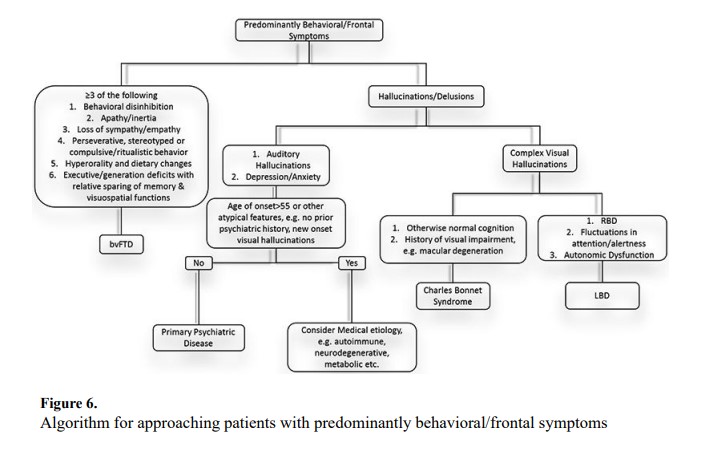

Accurately diagnosing patients with predominantly behavioral or frontal symptoms can be challenging due to symptom overlap with primary psychiatric disorders. Accurate differentiation is important due to differences in treatment approaches for these conditions. Figure 6 outlines our algorithmic approach to patients with behavioral/frontal syndromes. BvFTD should be considered in younger individuals with disinhibition, new-onset apathy, loss of empathy, perseveration, hyperorality, and/or executive dysfunction.41 Some of these symptoms may seem benign and interpreted as personality nuances or “quirks” by friends and family. Critical to determining the significance of these traits is whether they are different from the patient’s premorbid personality.

Hallucinations/delusions are referred to as psychosis, which may occur in both primary psychiatric diseases and neurological disorders. LBD should be considered in patients with complex visual hallucinations, especially when accompanied by parkinsonism, cognitive fluctuations, and/or RBD.29 Charles Bonnet syndrome consists of visual hallucinations in individuals typically presenting with vision impairment/loss, e.g. trauma, macular degeneration, etc.

Hallucination characteristics can guide clinicians towards specific etiologies. Auditory hallucinations are suggestive of primary psychiatric disease. Red flags suggestive of non-psychiatric disease include new-onset visual hallucinations in patients without a prior history of psychiatric disease, visual hallucinations onset after age 55, and new visual hallucinations in individuals who previously had only auditory hallucinations.42 These findings may be manifestations of autoimmune limbic encephalitis, which should be investigated with brain MRI, EEG, and CSF analysis including autoantibody testing.43 These patients should also undergo sex-appropriate cancer screening given the association between certain autoantibodies and malignancy. For example, ovarian teratoma is the hallmark malignancy associated with NMDA receptor encephalitis.

Approach to Patients with Cognitive & Motor Impairment