Pediatric critical illness is fortunately rare and the task of every pediatric practitioner (whether in the office, urgent care, or ED setting) is to diagnose compensated shock [and other critical illnesses] at the earliest possible time so that life saving treatment can be started. But it is not easy. And that’s because, critical pediatric illness is, thankfully, rare; and so recognizing it early can be like finding a needle in a haystack.

So today I’m reviewing Resource (1) of the three emergency medicine articles on using vital signs to alert practitioners to potentially life threatening pediatric illness [See Resources below].

And here is the Conclusion of Resource (1):

Patients with SIRS vital signs represented 15.2% of complete medical ED visits with vital signs recorded at a tertiary pediatric hospital, and the majority of patients with these vital signs were discharged without intravenous therapy and without readmission. Patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome vital signs had statistically significant and clinically modest increased risks of critical care, admission, and ED intervention. However, SIRS vital signs have a low sensitivity

for critical illness, making the vital signs poorly suited for use in isolation as a screening test for children requiring resuscitation for sepsis.

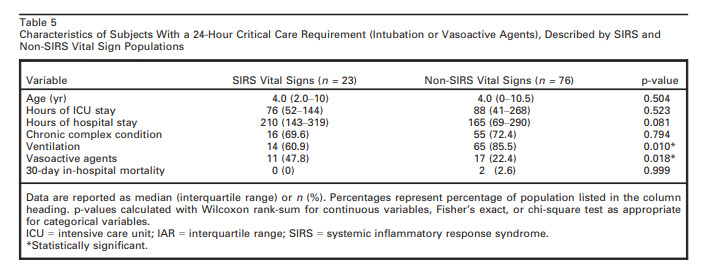

And we learn from the study that more children without SIRS vital sign pairs (76) then with SIRS vital sign pairs (23) required 24-hour critical care which the study authors define as requiring a ventilator or vasoactive medicication.

What the above means is that every infant and child needs a complete physiologic assessment regardless of vital signs. And I think that the best site for reviewing the complete pediatric assessment is the website Spotting The Sick Child (3rd Ed, 2015) [when I visited the site today, there was a notice that it is undergoing maintenance – hopefully it will be back online soon].

The following are excerpts from Resource (1) below, The prevalence and diagnostic utility of systemic inflammatory response syndrome vital signs in a pediatric emergency department [link is to full text HTML]:

Sepsis is a leading cause of pediatric death, with mortality rates between 8 and 10%.1,2 Challenges in diagnosing compensated septic shock in children are an important barrier to timely, guideline-compliant care.3

Consensus pediatric SIRS definitions require the presence of two or more of the following, one of which must be abnormal temperature or leukocyte count:

- coretemperature <36 or >38.5°C,

- tachycardia (or bradycardia in infants),

- tachypnea,

- leukocyte count elevated or depressed for age, or >10% immature neutrophils

- (DataSupplement S1, available as supporting information in the online version of this paper).8

- A modification to this approach includes use of a formula to correct heart rate for temperature elevations, but this has not been included in formal definitions.9,10

- Additionally, EDs have adopted screening approaches incorporating only the vital sign criteria from SIRS, because leukocyte counts are not known at the time of triage.10,11

This study sought to determine the prevalence of SIRS vital signs, to determine the severity of illness of patients with SIRS vital signs, and to examine the test characteristics of SIRS vital signs for identifying critical illness among pediatric medical ED visits. The hypothesis was that children with SIRS vital signs

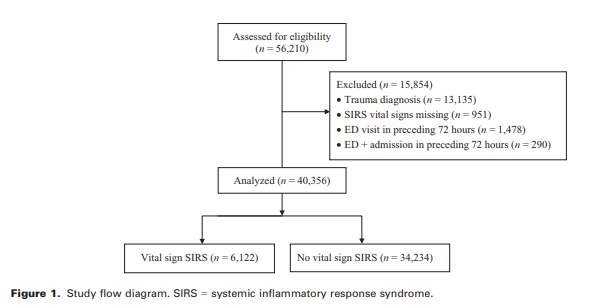

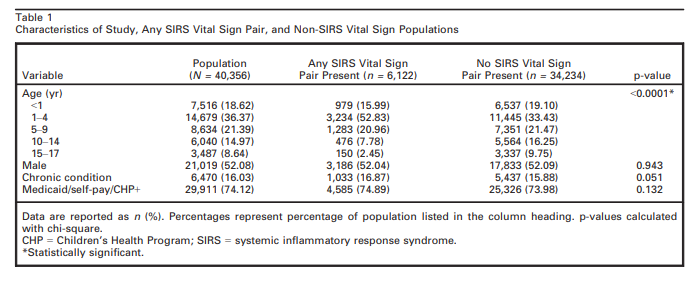

would have higher rates of hospitalization and critical illness when compared with all other children without SIRS vital signs presenting for medical (nontrauma) complaints to the ED. Additionally, the study sought to determine whether specific combinations of SIRS vital sign criteria improved the predictive value of SIRS vital signs.All visits to the ED of a tertiary academic free-standing pediatric hospital between April 2011 and March 2012 were screened for inclusion in this study.

Measures

The primary predictor was presence of SIRS vital signs recoded in the ED medical record. SIRS vital signs were defined as any two concurrent vital signs meeting SIRS criteria during the ED encounter, one of which was temperature.8 SIRS vital signs were analyzed as predictors, because they represent the only data known on a patient in triage before laboratory results are available, which matches ED practice environments. Each vital

sign comprising SIRS was individually analyzed and vital sign pairs that comprise SIRS were evaluated as predictors (temperature–heart rate, temperature–respiratory rate). In addition, a temperature–heart rate correction was performed following published practices (for each 1°C above 38.5°C, 10 beats/min was subtracted from the heart rate); corrected heart rate SIRS represents patients whose heart rate met SIRS criteria after temperature correction.9,12 Patients meeting hypothermia

and bradycardia criteria were described separately from patients meeting fever and tachycardia criteria, but all alterations in heart rate (tachycardia and bradycardia) and temperature (hypothermia or fever) were considered together in analysis. We additionally examined the presence of a heart rate meeting SIRS criteria on final ED vital signs as a predictor variable and compared it both to the entire population and to the population of patients with more than one set of vital signs

recorded.The primary outcome measure was requirement for critical care within 24 hours of ED arrival. Critical care was defined as receipt of a vasoactive agent infusion or intubation, to avoid the potential influence of institutionspecific criteria for intensive care unit (ICU) admission. Secondary outcomes were ICU admission from the ED, admission, 30-day in-hospital mortality, 72-hour readmission to an inpatient service, ED laboratory evaluation (including point-of-care tests), and ED IV therapy. Complex chronic conditions were identified by presence

of validated ICD-9 codes in the visit’s billing record.13RESULTS

The following paragraph is, I think, the most important of the whole paper:

Univariate analysis of ED testing and treatment patterns

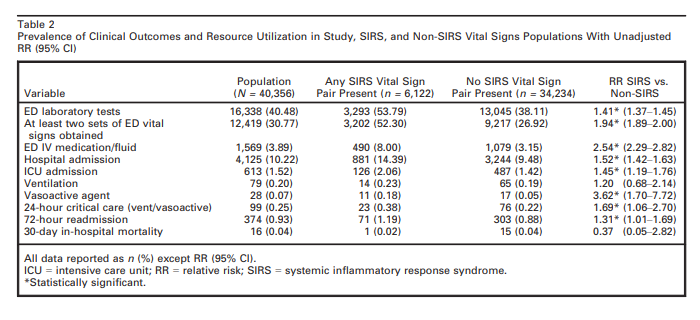

and clinical outcomes are shown in Table 2. These demonstrate a significantly increased RR of critical care requirement, ICU admission, ED laboratory tests, repeat vital signs, IV therapy, and admission and readmission in patients with SIRS vital signs compared to patients without SIRS vital signs. However, the overall proportion of patients with critical care and ICU admission outcomes was small in both SIRS vital signs and nonSIRS vital signs populations. Although the proportion of patients requiring critical care was minimally higher in the SIRS compared to the non-SIRS vital signs groups, in absolute numbers, the majority of these patients were in the non-SIRS vital signs group (Table 2). [Emphasis added]

What Table 2 above tells us is that the we can’t relax in patients who don’t have SIRS Vital Sign pairs. More children without SIRS vital sign pairs (76) then with SIRS vital sign pairs (23) required 24-hour critical care (vent/vasoactive).

What the above means is that every infant and child needs a complete physiologic assessment regardless of vital signs. And I think that the best site for reviewing the complete pediatric assessment is the website Spotting The Sick Child (3rd Ed, 2015) [when I visited the site today, there was a notice that it is undergoing maintenance – hopefully it will be back online soon].

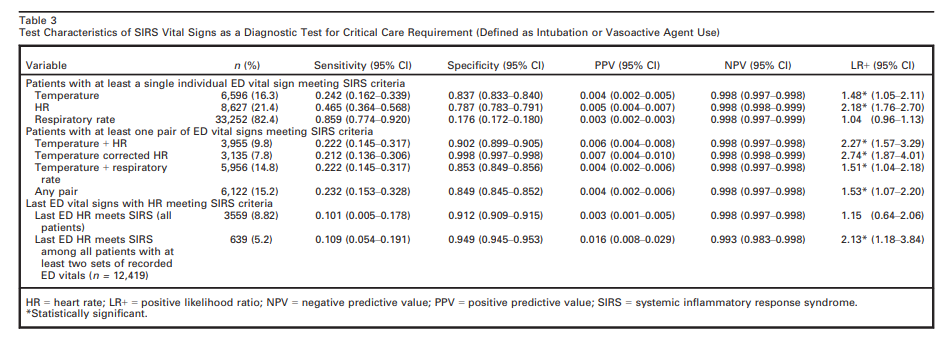

Test characteristics of SIRS vital signs for predicting critical care requirement are shown in Table 3. SIRS vital signs had a low sensitivity and PPV for critical care requirement, an outcome that occurred in only 0.25% of visits in our data set. Further analysis of specific combinations of SIRS vital signs demonstrates that the pair of temperature and corrected heart rate vital signs had the highest LR+ for predicting critical care requirement.

There were three patients in the study population who met SIRS criteria with bradycardia, of whom one required critical care and two were admitted to the ICU. There were 79 patients who met SIRS criteria with hypothermia, of whom none required critical care and five were admitted to the ICU. Given the small numbers of patients in these categories, additional analyses of

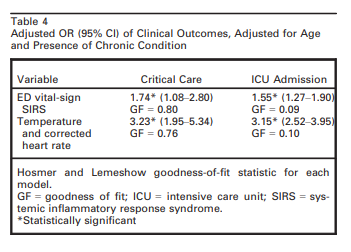

these subgroups were not undertaken.In multivariate analysis of the most predictive pair of vital signs, temperature and corrected heart rate, with age and chronic condition as covariates, the AOR for the outcomes of critical care and ICU admission were higher than using any pair of SIRS vital signs as a predictor (Table 4).

Patients with the primary outcome of critical care are

described in Table 5. Patients with SIRS vital signs were more likely to require critical care due to a need for vasoactive agents, while patients without SIRS vital signs were more likely to require critical care due to a need for ventilation.SIRS vital signs were the first recorded ED vital signs in 82.1% of patients with SIRS vital signs. Among patients with SIRS vital signs, 52.3% had more than one set of vital signs recorded in the ED, compared to 26.9% of patients without SIRS vital signs (p < 0.0001). Of patients with more than one set of vital signs recorded, 5.15% demonstrated heart rates meeting SIRS criteria on their final recorded vital signs. These patients were more likely to require critical care than patients whose final heart rates did not meet SIRS criteria (Table 3).

Only 10.7% of the study population had white blood cell counts measured. In patients with SIRS vital signs, 16.3% had white blood cell counts recorded, while in patients without SIRS vital signs 9.7% of patients had white blood cell counts tested, a difference that was significant (p < 0.0001).

Among SIRS vital signs patients, 5,064 (82.7%) were discharged from the ED; 71 of these had IV therapy in the ED at the index visit or readmission to the hospital within 72 hours. This left 4,993 (81.6%) SIRS vital signs patients discharged from the ED without IV therapy and without 72-hour readmission.

Discussion

This study demonstrated limitations to existing SIRS

vital sign criteria as an isolated predictor of critical illness

in an ED pediatric population. Contributing to

these findings is the rare occurrence of critical illness

and 30-day in-hospital mortality among patients presenting

to this tertiary care pediatric ED for medical

care and the high prevalence of SIRS vital signs.Additionally, the high prevalence of SIRS vital signs

has potential to increase testing and treatment or lead

to alert fatigue. It is noteworthy that 92% of patients

with fever meet SIRS criteria and that temperature criteria

alone demonstrate virtually identical test characteristics

to any pair of SIRS vital signs. Even considering that early ED IV fluid and antibiotics might prevent patients from requiring critical care, IV therapies were only administered to 8% of patients with SIRS vital signs, leaving the overwhelming majority of SIRS vital sign patients who required neither IV treatment nor critical care.Among existing criteria, the pair of temperature and heart rate vital signs demonstrated the strongest associations with outcomes, particularly temperature-corrected heart rate, which increased PPV without sacrificing NPV compared to other SIRS vital sign pairs. If SIRS-based vital sign screening criteria are employed, use of the temperature-corrected heart rate parameter alone appears to be the optimal choice.

Resources:

(1) The prevalence and diagnostic utility of systemic inflammatory response syndrome vital signs in a pediatric emergency department [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Link to the PDF download on the HTML link]. Acad Emerg Med. 2015 Apr;22(4):381-9. doi: 10.1111/acem.12610. Epub 2015 Mar 16.

(2) Prognostic accuracy of age-adapted SOFA, SIRS, PELOD-2, and qSOFA for in-hospital mortality among children with suspected infection admitted to the intensive care unit [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Intensive Care Med. 2018 Feb;44(2):179-188. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-5021-8. Epub 2017 Dec 19.

The above is an interesting article but I was unable to glean any relevant data for pediatric decision-making.

However, the article’s supplementary material, Supplementary material 1 (DOCX 133 kb) contains on pp 5 – 10 of the Word document Supplementary Table 1: Definitions to construct age-adapted scores for SIRS, severe sepsis, age-adapted SOFA, PELOD-2, and qSOFA (that is, the physiological parameters that were used for organ dysfunction).

(3) Pediatric Vital Sign Distribution Derived From a Multi-Centered Emergency Department Database [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Front Pediatr. 2018 Mar 23;6:66. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00066. eCollection 2018.