In this post I link to the Internet Book of Critical Care‘s [Link is to Table of Contents] Atrial Fibrillation (AF) & Flutter complicating critical illness. January 6, 2017 by Dr Josh Farkas.

Dr. Farkas’ chapter on atrial fibrillation is simply the best I’ve ever read.

Note to myself: Although the chapter is very complete, it is also a very fast review. So just review the whole chapter.

Here are direct links that Dr. Farkas has provided us to various sections of his chapter.

CONTENTS

- Introduction

- Diagnosis of AF

- Prevention of AF

- Investigation of the cause of AF

- Management – Overall approach

- Atrial flutter

- Podcast

- Questions & discussion

- Pitfalls

- PDF of this chapter (or create customized PDF)

Pitfalls

- Always look for other causes of instability among patients with AF and shock or difficulty controlling the ventricular rate. In some patients, this may be a “sinus tach equivalent” which is due to an underlying problem (e.g., sepsis, PE). In such patients, successful management depends on treating the underlying problem. Merely trying to squash the heart rate can be dangerous among these patients, as it may suppress a compensatory tachycardia.

- ACLS guidelines typically recommend immediate cardioversion for unstable patients with AF. However, among critically ill patients this has a low success rate.

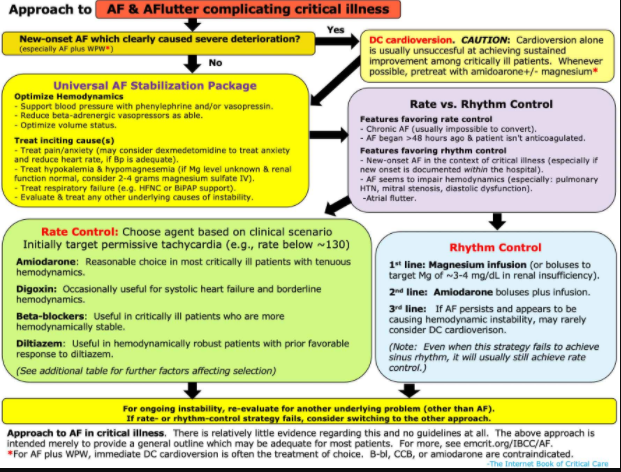

Overall Approach To Atrial Fibrillation

Emergent Cardioversion

how much is AF actually contributing to the patient’s instability?

- The key question is: What is driving the instability? Is the atrial fibrillation causing the patient to be unstable? Or is atrial fibrillation merely triggered by underlying instability?

- Some key pieces of information can help:

- (1) Heart rate: As a general rule, heart rates <150 are less likely to cause hemodynamic instability. The faster the heart rate is, the more likely it is causing trouble.

- (2) Structural heart abnormalities (especially pulmonary hypertension, mitral stenosis, or diastolic heart failure) may render patients dependent on atrial kick. Such patients may tolerate AF poorly.

- (3) Overall clinical context.

- Trying to sort this out is important:

- DC cardioversion will stabilize the patient only if the AF is causing the instability.

- ⚠️ If fast heart rate is due to an underlying process, then overly aggressive attempts to reduce the heart rate to a “normal” range may make matters worse (because a mild degree of tachycardia may actually have a compensatory, beneficial effect).

consider immediate DC cardioversion

- DC cardioversion is indicated if new-onset AF clearly caused the patient to be severely unstable. This is unusual – for most critically ill patients, the AF isn’t the primary driver of instability.

- ⚠️ Stand-alone cardioversion will usually fail as a strategy for AF management in critical illness.(12576943) Even if cardioversion is successful, patients will usually revert to AF subsequently.

- If possible, pretreatment or post-treatment with amiodarone +/- magnesium may enhance the likelihood of achieving and maintaining sinus rhythm.

AF with an accessory pathway (Wolff Parkinson White)

- An accessory pathway is an aberrant electrical connection between the atria and the ventricles that shouldn’t exist.

- Normally, when in AF the heart rate is limited by the refractory period of the AV node. Although the AV node may allow for a fast heart rate (e.g. ~120-180), these heart rates are usually tolerated reasonably well.

- When AF occurs in the context of an accessory pathway, both the AV node and the accessory pathway can transmit beats to the ventricles. Since the accessory pathway often has a shorter refractory period than the AV node, it may drive the ventricle very rapidly (e.g. >200). This is dangerous because the extremely fast and uncoordinated contractions of the ventricle can promote ventricular tachycardia or cardiovascular collapse.

- AF with an accessory pathway produces a fairly distinctive pattern of EKG findings:

- Irregularly irregular heart rate that may be extremely fast (e.g. >200).

- Wide-complex beats can result from transmission over the accessory pathway.

- Morphology varies between different beats (some beats are fusion complexes if the AV node and the accessory pathway fire at a similar time).

- AF with an accessory tract shouldn’t be treated with medications that impair the AV node (eg. beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, or amiodarone). Blockade of the AV node may merely cause a greater dominance of the accessory pathway, exacerbating matters (to a certain extent, the AV node and the accessory pathway are competing for control of the ventricle). Antiarrhythmics which may be used are procainamide or ibutilide.

- This is a unique situation where DC cardioversion is usually the treatment of choice (based on its efficacy and speed). If a patient with AF and an accessory pathway is displaying instability, proceeding directly to DC cardioversion is indicated.

universal AF stabilization package

The most important intervention for critically ill patients with AF is usually treating the causes of AF. There is a risk of getting overly focused on antiarrhythmics and cardioversion, but the most important interventions are often as follows:

hemodynamic optimization

- (1) Discontinue beta-adrenergic vasopressors as able.

- Especially epinephrine and dobutamine may increase heart rate and should be weaned if possible.

- (2) For hypotension, add pressors that don’t stimulate beta receptors.

- Phenylephrine is a good choice if needed to support blood pressure, without driving tachycardia. Phenylephrine infusions are often avoided due to fear that they will reduce the cardiac output, but they generally don’t reduce the cardiac output. Phenylephrine usually increases preload by causing venoconstriction, thereby balancing out the effects of increasing the afterload.(discussed here)

- Vasopressin is another option.

- (3) Optimize volume status.

- AF may be caused by volume overload, which causes atrial dilation. If volume overload is present, diuresis may be beneficial.

- If frank hypovolemia is present, then volume administration may be beneficial. However, note that hypovolemia is relatively uncommon among patients who are admitted to ICU.

treatment of pain/anxiety/withdrawal

- Untreated distress can drive sympathetic tone and aggravate AF.

- Pain and anxiety should always be treated adequately. However, uncontrolled AF may serve as a reminder to make especially sure that these issues are being attended to (see chapters on anxiety and pain).

- For uncontrolled anxiety, dexmedetomidine may be considered as an anxiolytic that will reduce sympathetic tone and decrease heart rate.

There is much more in Dr. Farkas’ chapter which I have not excerpted.

Note to myself: Finish the review by going to and reviewing the rest of the chapter:

CONTENTS (continued)

- Atrial flutter

- Podcast

- Questions & discussion

- Pitfalls

- PDF of this chapter (or create customized PDF)

Pitfalls

- Always look for other causes of instability among patients with AF and shock or difficulty controlling the ventricular rate. In some patients, this may be a “sinus tach equivalent” which is due to an underlying problem (e.g., sepsis, PE). In such patients, successful management depends on treating the underlying problem. Merely trying to squash the heart rate can be dangerous among these patients, as it may suppress a compensatory tachycardia.

- ACLS guidelines typically recommend immediate cardioversion for unstable patients with AF. However, among critically ill patients this has a low success rate.