In this post I link to and excerpt from CORE IM’s 5 Pearls on PPI. Posted: August 29, 2018

By: Dr. Cary Blum, Dr. Martin Fried and Dr. Shreya P. Trivedi

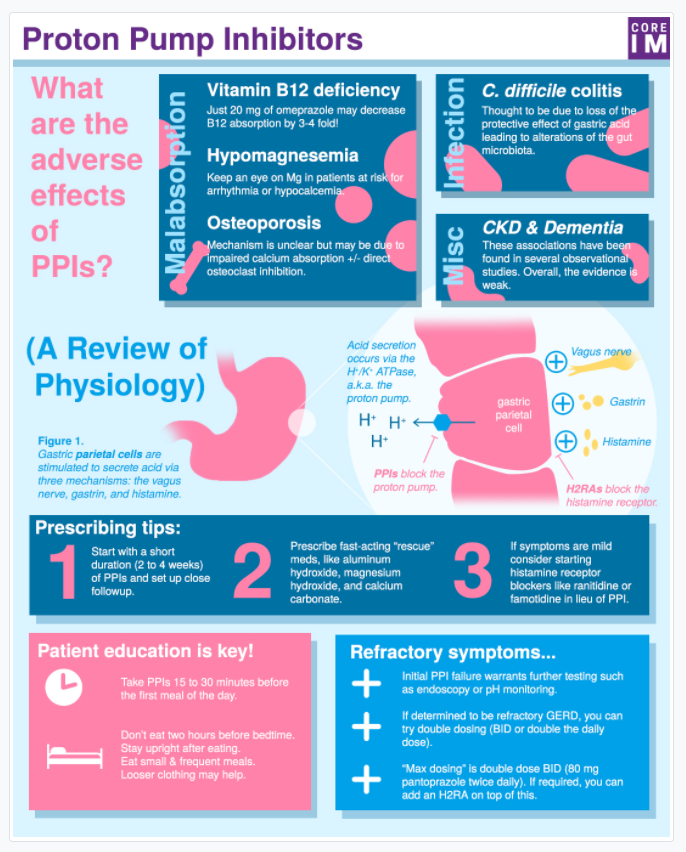

Graphic: Dr. Michael Shen

Audio: Harit Shah

Peer Review: Dr. Peter Stanich

Show Notes Podcast Transcript References

All that follows is from the above excellent resource.

Show Notes

- 2:02 What are associated adverse effects for patients are on long-term PPIs?

- 10:57 What are some strategies to get your patient off PPIs?

- 13:30 How do histamine-2 (H2) receptor antagonists blockers work and how can it explain why H2 blockers might not be as effective as PPIs?

- 16:48 How should you educate patients to take PPIs to get the maximize benefit?

- 21:41 How do you manage ongoing symptoms in patients on PPIs?

Podcast Transcript [Link is to the full podcast transcript]

M: A quick disclaimer –

C: In this episode, we assume more serious pathology has already been considered and ruled out, either by history or more advanced testing. And unless otherwise specified, in this podcast we are primarily referring to management of GERD.*

*If there is a possibility of something more serious, consider upper GI endoscopy and/or PH testing.

[Sweeper – Pearl 1- Risks of PPIs]

C: . . . so when I think about adverse effects of PPI I divide them into two big buckets – those related to malabsorption and those related to infection.

C: . . . there’s also likey a third “miscellaneous” category, of conditions that are associated with PPI use but the mechanism is very sketchy. CKD is in this category. Its weakly but statistically associated with PPI use in observational studies but the absolute risk comes out to only 1 to 3 additional cases in 1000 patient years.

S: I think dementia probably belongs third miscellaneous category.

C: For sure. Early studies also showed an association between PPIs and dementia, but more recent studies have failed to replicate these findings.

S: Ah nice, that’s really good to know–but how did I know you were gonna go and make things more confusing with a “third category”? Let’s get back to the two buckets of malabsorption and infection. What are the big issues related to the first–malabsorption?

C: Three main complications related to malabsorption – Vitamin B12 deficiency, low magnesium levels and osteoporosis.

There are three buckets: Malabsorption, Infection, and Miscellaneous

The first malabsorption problem is Vitamin B12 deficiency.

S: B12! I’m starting to see the connections with your patient Cary. Vitamin B12 levels are often checked in the initial workup of reversible causes of dementia.

C: That’s definitely true and the combination of initial memory complaints of my patient and long-term PPI use led me to send off levels, which were super low. I started repleting right away.

C: There is pretty strong evidence that PPIs diminish B12 absorption, but the absolute excess risk of developing vitamin deficiency is not huge–something on the order of 3 to 4 cases per 1000 person years, translating to a relative increase of 60 to 70% over patients not on PPIs.

C: My practice now is to monitor patients’ B12 levels about annually if they are on PPIs.

The next malabsorption from PPIs is hypomagnesemia

C: The absolute risk of low magnesium individual patients is likely small, but the association is convincing and PPI’s even carry an FDA warning regarding hypomagnesemia. A meta-analysis of 9 studies confirmed that people on long term PPI therapy have an almost 50% greater relative risk for low magnesium levels than a control group. We’ll link that paper in the show notes.

S: The other big thing is–low magnesium predisposes to other electrolyte problems like hypocalcemia.

The final malabsorption issue is osteoporosis and fracture.

C: . . . the third major malabsorptive issue [is] – osteoporosis and fracture.

C: . . . . I will say the mechanism is a bit hand-wavy involving impaired calcium absorption and also possibly direct osteoclast inhibition. But a convincing association does exist.

M: Yeah? Lay it on us

C: The best data comes from the Nurses Health Study – you guys know that long term prospective cohort study of women. The authors observed a 35% relative increase in risk of hip fracture after 2+ years of PPI use. The thing is–this association was driven almost entirely by smokers, and when only never-smokers were considered, no statistically significant association was detected.

M: If this were Mythbusters I’d definitely label the risk of osteoporosis plausible though not sure we have enough data to confirm it.

S: I’d have to agree. Maybe i’ll be on the lookout more for osteoporosis in my patients who have combined hit of smokers and on PPIs.

C: Yeah I think that sounds about right.

The next bucket is infectious.

C: This is much smaller [bucket] and really limited to C. diff and other forms of colitis.

S: Yes yes, I’ve definitely heard about risk for C. diff infection. So let’s talk about the data first and then the mechanism.

C: Again the data is all observational, but pretty strong associations here. A 2012 meta-analysis of FORTY TWO studies showed the pooled odds ratio of C. diff infection in PPI users was 1.74 with the confidence interval going from 1.47 to 2.85.*

*For an explanation of the odds ratio, please see Interpreting Results Of Case-Control Studies from the Centers For Disease Control And Prevention, accessed 11-12-2021.

S: Ok so that’s real. Any data on recurrent C. diff?

C: You betcha. I don’t have the numbers offhand but there is also an association with higher rates of recurrent C. Diff.

M: You know C. diff is something we see all the time on the inpatient side and I never think about addressing the PPI use on the discharge medication reconciliation. It is definitely something to think about in the future…

S: For sure. Is there any thought into the causal mechanism behind PPis and c.diff?

C: The authors of the meta analysis propose it could be due to loss of the protective effect of gastric acid and/or changes in the gut microbiota.

C: And [finally] there’s the “miscellaneous” bucket that includes weaker associations like CKD and dementia.

[Sweeper – Pearl 2 – De-prescribing]

See transcript for details on the above.

[Sweeper Pearl 3 – H2 Blocker mechanism and less effective for dyspepsia]

See the infographic at top of the post and transcript for an explanation of the pharmacology of PPIs and H2 blockers.

[Sweeper – Pearl 4 – PPI patient education]

M: So how long before a meal should PPIs be taken?

C: Ideally about 15-30 minutes. Despite having a long duration of action due to suicide inhibition of the pump, PPI’s have a short half life in circulation, so taking the PPI at the right time is pretty important. You want the drug to be in circulation when the parietal cell is activated!

S: OK so timing is important–but how important really? It’s easy for us to say “take this pill 15 minutes before a meal” but you know, for some patients, it can be kinda hard.

C: The importance of timing was shown quite elegantly in a study of healthy volunteers.

C: . . . these healthy subjects underwent continuous esophageal pH monitoring for two separate periods of 7 days each. During period 1, a PPI was taken 15 minutes before breakfast. During period 2, the PPI was taken at the same time in the morning, the pt’s fasted until at least noon. The authors found that when PPIs were taken shortly before a meal, there was about a 60% reduction in the duration of acidic conditions.

S: A 60% difference is a major deal. Alright, one more question, Cary, does it matter which meal the PPI should be taken before? Does 15 minutes before lunch or dinner work just as well as 15 minutes before breakfast?

C: Glad you asked Marty. Ideally, the PPI should be taken before the first meal of the day. This is because the longer one fasts prior to eating, the more proton pumps are activated in response to a meal.

M: Think of it like overnight while you are fasting your proton pumps are just building up in the cells for a morning time proton ambush!

M: The main takeaway here is that patients who must be on PPIs really should take it 15 to 30 minutes before breakfast. This ensures that the medication is in the serum and ready to work once the parietal cell is activated and the proton pumps migrate to the luminal surface where the PPI will be secreted and block acid secretion.

[Sweeper – pearl 5 – monitoring and follow-up]

S: Let’s finish out our PPI discussion with some more management issues – what to do when patients are still reporting symptoms while on the PPI?

M: [in a loudspeaker voice] Sir, step away from the Siracha. Put the Franks down, and take three steps back from the chili pepper flakes…

C: Well yes, obviously reviewing diet and medication timing is important here. But like any other situation in medicine when the plan isn’t working as, well, planned, we should reconsider the diagnosis.

S: Super important! PPIs are super effective at reducing acid secretion in nearly all patients when taken correctly–I know we did our fair share of PPI-bashing in the beginning of the episode, but patients and doctors alike continue to use them because they work and are by-and-large safe.

M: Right, ho many times can you name when an entire class of drugs went from prescription to over-the-counter?

S: So if the symptoms truly continue through PPI therapy, and the drug is being taken correctly ie 30 mins before meals, preferably before breakfast, we should have a low threshold to refer for endoscopy.

M: Yeah i mean that kind of goes back to the disclaimers to start the podcast, and PPI failure might be an indication that we’re not dealing with straightforward GERD.

S: And endoscopy can look for things that PPIs won’t treat, like hiatal hernias or malignancy.

M: So true. So let’s say the upper scope comes back benign with the presumptive diagnosis remaining GERD. What medication options are available at this point?

S: I’ve seen GI double up the PPI.

C: Yep, and you can double in two ways – you can make the dosing twice-daily or you can make it a double-dose in the morning to maintain once-daily dosing. And if patients STILL have symptoms you can pump it all the way up to double dose BID, which is considered “max” dosing.

M: So would that be like 80mg pantoprazole twice daily?

C: Exactly.

S: What about using H2 blockers plus PPIs?

C: The addition of H2RA can be considered once maxed on PPI. I would only do this if there’s actual evidence of continued acid reflux on esophageal pH testing, because realistically the potential benefit slim.

M: And for the reasons mentioned above, I would still take PPI first in the morning 30 mins before meals to ensure the parietal cells are maximally activated. Then you can add the ranitidine later because it’s faster acting and not reliant on parietal cell activation… matter of fact it prevents it!

S: Ahh great point Marty. So let’s review this pearl. A diagnostic “time out” is warranted for patients who continue to experience symptoms despite being on PPI therapy AND taking it correctly. Have a low threshold for further testing – be it upper endoscopy or pH testing – to rule out other etiologies. In the case of true, refractory reflux PPI dosing can be increased both by adding an evening administration and/or doubling the dose. This 4x dosage is considered max therapy, and additional H2 blocker therapy can be considered but the additional benefit is likely minimal.