In this post, I link to and excerpt from Emergency Medicine Cases‘ Ep 172 Syncope Simplified with David Carr. August, 2022.*

*Helman, A. Carr, D. Syncope Simplified. Emergency Medicine Cases. August 2022. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/simplifying-syncope. Accessed August 5, 2022

All that follows is from the above resource.

The ED approach to syncope is almost entirely based on a focused but thorough history, cardiac physical exam and ECG rather than laboratory tests and imaging. The first step is distinguishing syncope from seizure. The next step is distinguishing cardiac from non-cardiac syncope. Our ultimate aim is to make safe disposition decisions based on this approach.

Distinguishing syncope from seizure based on history

The most useful symptoms reported by patient/witness for identifying seizure

- Head turning during event – sensitivity 43%; specificity 97%; LR 14

- Unusual posturing during the event – sensitivity 35%; specificity 97%; LR 13

- Absence of presyncope – sensitivity 77%; specificity 86%; LR 5.6

- History of epilepsy – more likely seizure

- Post-ictal state – 96% of patients with seizures

- Urinary incontinence – sensitivity 24%; specificity 96%; LR 6.7 *despite this impressive LR, urinary incontinence cannot reliably distinguish syncope from seizure

The most useful findings evaluated by the physician for identifying patients with seizures:

- The presence of a cut tongue – sensitivity 45%; specificity 97%; LR 17

- Lateral tongue bite has a 100% specificity for tonic clonic seizure

- Patient has no recall of unusual behaviors before the loss of consciousness – sensitivity 53%; specificity 87%; LR 4.0

The most useful symptoms reported by patient or witness for identifying patients with syncope:

- Loss of consciousness with prolonged sitting or standing (sensitivity 40%; specificity 98%; LR 20

- Dyspnea before loss of consciousness (sensitivity 24%; specificity 98%; LR 13

- Palpitations before loss of consciousness (sensitivity 34%; specificity 96%; LR 8.3

- Muscle tone (increased tone more likely seizure, decreased tone more likely syncope)

- Number of limb jerks – The 10:20 Rule: patients with witnessed <10 myoclonic jerks after sudden loss of consciousness is more like syncope vs >20 myoclonic jerks is more likely seizure

Clinical Pitfall: Even though the +LR for urinary incontinence increases the likelihood of seizure, urinary incontinence cannot reliably distinguish seizure from syncope and should not be relied on to do so.

Clinical Pearl: Lateral tongue bite after sudden loss of consciousness has a 100% specificity for tonic clonic seizure.

Clinical Pearl: Approximately 90% of people who have a syncopal episode will have myoclonic jerks, the 10:20 Rule to help determine whether syncope or seizure is more likely. If there are <10 jerks it is more likely to be syncope, if you have >20 jerks it is more likely to be a seizure.

Distinguishing cardiac syncope from non-cardiac syncope

After considering syncope caused by diagnoses that typically present with additional clinical features (eg vascular catastrophes such as subarachnoid hemorrhage, ectopic pregnancy, massive GI bleed, ruptured AAA etc) the priority in the ED should be distinguishing cardiac syncope from non-cardiac syncope.

Categories of syncope

- Reflex syncope – vasovagal, carotid sinus syndrome, situational

- Orthostatic syncope – drug induced, volume depletion, neurogenic

- Cardiovascular syncope – mechanical (PE, tamponade, aortic stenosis), dysrhythmias

Cardiac syncope clinical clues

- Cardiovascular risk factors

- Structural heart disease (especially HCM, aortic stenosis)

- Pacemaker

- Sudden syncope with no prodrome

- Exertional syncope

- Prodrome that includes palpitations, shortness of breath or chest pain

- Associated facial injury (including dental injury, eye glasses damage, tip of tongue bite)

- Family history of unexplained sudden death, drowning or single MVC <50 years of age

- Aortic stenosis murmur – high mortality rate in patients with critical aortic stenosis and syncope

Clinical Pearl: when asking about a family history of premature sudden death, also ask about unexplained drownings or single vehicle collisions, as these might point to an underlying inheritable cardiac cause

Clinical Pearl: older patients with aortic stenosis, a valve diameter <1cm and a syncopal episode have very poor prognosis, and high mortality rate – so use your stethoscope and auscultate the chest; an aortic valve repair can be life-saving in this setting

Clinical Pitfall: do not assume that a patient who has a pacemaker has orthostatic or reflex syncope; their pacemaker needs to be interrogated

Reflex Syncope

Clinical clues – prodrome of feeling warm/nausea, history of recurrent syncope after an unpleasant sight, sound, smell or pain, prolonged standing, during a meal, being in crowded/hot places, autonomic activation (carotid sinus massage/shaving, pressure on the eye/ocular-bradycardic reflex, micturition, defecation).

Physical Exam – despite reports from the cardiology literature stating that carotid sinus massage is useful in patients with unexplained syncope, our expert does not see a role for carotid sinus massage to diagnosis reflex syncope in the ED.

Eagle’s Syndrome – a rare but morbid cause of reflex syncope

While the vast majority of reflex syncope etiologies are benign, Eagle’s Syndrome is a rare cause of syncope that involves a calcified, elongated stylohyoid ligament that presses on the carotid during neck extension and can lead to syncope, tinnitus and throat pain or mimic stroke syndromes/dissection. It is identified on CT scan. Surgical management can prevent further syncopal episodes.

Clinical Pearl: Eagle’s Syndrome is a rare cause of syncope that involves a calcified, elongated stylohyoid ligament that presses on the carotid during neck extension and can lead to syncope; in patients who present with recurrent syncope after activities that involve neck extension (eg car mechanic, yoga, star-gazing etc) with associated tinnitus or throat pain, consider a CT of the neck to rule out Eagle’s syndrome.

Orthostatic Syncope

Clinical Clues – prodrome of lightheadedness after changing from lying/sitting to sitting/standing position, post-prandial hypotension, temporal relationship with start or change of dosage of vasoactive drugs/diuretics, autonomic neuropathy (diabetes, Parkinsonism), volume losses.

Clinical Pitfall: a common pitfall is assuming that the cause of syncope is orthostatic and failing to search further for cardiac causes in older patients who are found to have an orthostatic drop. Orthostatic vital signs do not predict 30 day serious outcomes in older emergency department patients with syncope. Many older patients will have an orthostatic drop at baseline, and some patients with orthostatic symptoms will not have an orthostatic drop; orthostatic vitals are non-specific and may lead to premature closure.

Source: Alboni P, Brignole M, Menozzi C, et al. Diagnostic value of history in patients with syncope with or without heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(7):1921-1928

Simple 7-step approach to ECG interpretation for syncope

ECGs are the most important test in patients with syncope, and in many cases of discrete syncope without other symptoms, an ECG is the only test required in the ED. It is important to scrutinize the rhythm strip or 12-lead ECG from EMS as it may reveal a transient cardiac dysrhythmia that does not appear on the ED ECG.

1.Brady- or tachydysrhythmias – including heart blocks, ventricular tachycardia etc – these are usually obvious

2.Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM): inheritable cardiac condition, number one cause of sudden death in young athletes (1:500 prevalence)

a) Voltage criteria for LVH in precordial and limb leads

b) Narrow, “dagger-like” Q waves in inferior and lateral leadsHypertrophic Cardiomyopathy ECG Source: Life in the Fast Lane blog

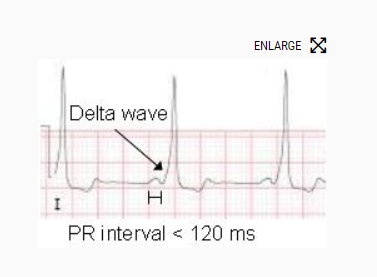

3.Wolf-Parkinson-White (WPW): short PR, delta wave (upsloping QRS)

ECG Examples:

- Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) ECG (Example 1)

- Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) ECG (Example 2)

- Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) ECG (Example 3)

- Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) Alternans ECG

Source: https://www.healio.com/cardiology/learn-the-heart/ecg-review/ecg-topic-reviews-and-criteria/wpw-review

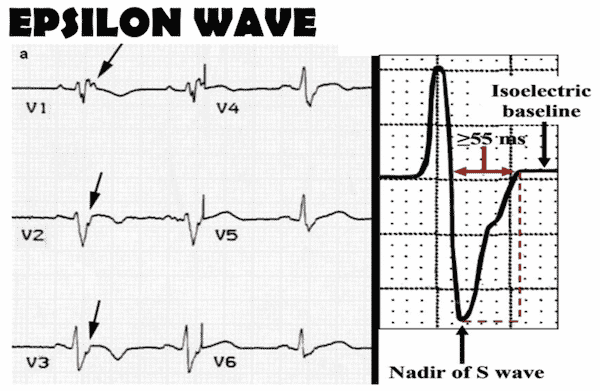

4. Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy (ARVC): T-wave inversion in V1,V2, V3 (unlike Wellen’s that is V1-V4), epsilon wave (looks like a reverse delta wave, with slurring of the downstroke of the QRS, from the nadir of the S wave to the isoelectric line +/- a notch)

*Imaging in Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia (ARVD)

Updated: Jun 11, 2018

Author: Kostaki G Bis, MD from emedicine.medscape.com

5.Brugada – down-sloping ST elevation in V1/2

_________________________________________

Brugada Types: Source: https://medschool.co/tests/ecg-disease-patterns/brugada-syndrome

Brugada syndrome is an inherited condition that strongly predisposes to sudden cardiac death. The condition is autosomal dominant in inheritance and involves a loss of function mutation in sodium channels, predominantly affecting the right ventricle.

ECG Findings in Brugada Syndrome

All findings must occur in at least one right precordial lead (V1-V3).

- Type 1 – coved ST elevation >2mm in V1-V3, followed by a negative T wave

- Type 2 – saddle-shaped ST elevation in V1-V3 that is >2mm at the J point and >=1mm at the terminal portion of the ST segment

- Type 3 – saddle-shaped ST elevation in V1-V3 that is >2mm at the J point and <1mm at the terminal portion of the ST segment

The presence of a type 1 pattern with at least one clinial criterion is diagnostic of Brugada syndrome.

Clinical Criteria for Diagnosis

At least one of:

- Documented VT / VF

- FHx sudden cardiac death <45 years

- Coved ECGs in family members

- Inducibility of VT with programmed electrical stimulation

- Syncope

- Nocturnal agonal respiration

The Brugada pattern in isolation is of unclear clinical significance, while the presence of clinical criteria with a type 2 or 3 pattern requires further investigation.

Drug Triggers of Arrhythmia in Brugada Syndrome

- Antiarrhythmics – flecainide, procainamide

- Psychotropics – amitriptyline, nortriptyline, lithium

- Anaesthetics – local anaesthetics, propofol

- Substances – alcohol, cannabis, cocaine

Brugada Types: Source: https://medschool.co/tests/ecg-disease-patterns/brugada-syndrome

_________________________________________

Clinical Pearl: Brugada often comes out when people are febrile and more arrhythmogenic, so think about this in patient with fever and palpitations and make sure you take a close look at the ECG – remember if you miss Brugada, the person has a 10% chance of death in the next year

ECG Cases in depth review and examples of Brugada: ECG diagnosis of Brugada

6. Long QT

7. Bifascicular block (especially in the presence of a first-degree block) in a patient with syncope are at high risk of degenerating into 3rd-degree block and often require a pacemaker

_________________________________________

Bifascicular Block from Life In The Fast Lane

Ed Burns and Robert ButtnerDec 9, 2021:Clinically, bifascicular block presents with one of two ECG patterns:

- Right bundle branch block (RBBB) with left anterior fascicular block (LAFB), manifested as left axis deviation (LAD)

- RBBB and left posterior fascicular block (LPFB), manifested as right axis deviation (RAD) in the absence of other causes

*Some authors describe Left bundle branch block (LBBB) as a bifascicular block, as it may indicate LAFB + LPFB. However, clinically the term bifascicular block is reserved for RBBB with either LAFB or LPFB

_________________________________________

Clinical pearl: one can cover most of ECG interpretation in the patient with syncope by simply looking for any abnormalities in the ECG intervals – PR, QRS and QT; this covers heart blocks, WPW, wide QRS tachydysrhythmias, HCM, Long QT syndrome and short QT syndrome

ECG Cases: ECGs in Cardiac Syncope

Is routine blood work necessary for patients who present to the ED with syncope?

In our expert’s view there is limited value in “routine” labs in patients deemed to be low-risk by physician gestalt. While troponins are often drawn in patients with syncope, evidence suggests that Troponin testing should be reserved for patients in whom the clinician suspects ACS and not drawn routinely in patients who present to the ED with syncope. Patients in whom labs should be considered:

- Suspect a bleed (CBC +/- coags)

- Suspect a PE (Dimer/CTPA)

- Suspect/possible pregnancy (B-HCG)

- Suspect an electrolyte abnormality based on medication change/ECG (lytes, extended lytes)

- Suspect ACS (i.e., chest pain or equivalent – troponin)

To image, or not to image: The value of CT head and PoCUS in syncope

Patients with clear cardiac syncope or reflex syncope do not routinely require a CT head. Imaging should be considered when secondary causes of syncope are suspected such as subarachnoid hemorrhage and vertebrobasilar “drop” attack stroke, and when non-trivial head injury as a result of the syncopal episode is suspected. Remember that for a CNS lesion to cause syncope directly, it needs to either effect both cerebral hemispheres or the brain stem.

Similarly, PoCUS should be considered when secondary causes of syncope are suspected, such as AAA, PE, aortic dissection or when major trauma results from the syncopal episode.