In this post, I link to and excerpt from Emergency Medicine Cases’ Ep 149 Liver Emergencies: Thrombosis and Bleeding, Portal Vein Thrombosis, SBP, Paracentesis Tips and Tricks.*

*Helman, A. Himmel, W, Steinhart, B. Episode 149 Liver Emergencies: Thrombosis and Bleeding, Portal Vein Thrombosis, SBP, Paracentesis Tips and Tricks. Emergency Medicine Cases. November, 2020. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/liver-emergencies-thrombosis-bleeding-portal-vein-thrombosis-sbp-paracentesis. Accessed 11-07-2022.

Note to my readers: I excerpt from the above show notes because doing so helps me reinforce my learning. You should use the official show notes at Ep 149 Liver Emergencies: Thrombosis and Bleeding, Portal Vein Thrombosis, SBP, Paracentesis Tips and Tricks

For part 1 of this series on Liver Emergencies go to Episode 148 Liver Emergencies: Acute Liver Failure, Hepatic Encephalopathy, Hepatorenal Syndrome, Liver Test Interpretation & Drugs to Avoid

All that follows is from the above podcast’s shownotes.

This is part 2 of our podcast series on liver disease for the ED doc with Walter Himmel and Brian Steinhart. We clear up the confusing balance between thrombosis and bleeding in liver patients, the elusive diagnosis of portal vein thrombosis, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis diagnosis and treatment and some tips and tricks on paracentesis. We answer questions such as: How is it that liver patients are at increased risk for both thrombosis and bleeding? How should we interpret the INR of liver patients in the setting of thrombosis or bleeding? Should a liver patient with an elevated INR be placed on an anticoagulant for portal vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism? Is there a role for TXA in the bleeding liver patient? Why were PCCs rarely indicated in the liver patient in the past, and now being reconsidered? Do you need to obtain an INR before performing a paracentesis? At what platelet count is it safe to perform a paracentesis? What are the indications for giving albumin after paracentesis? for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis? and many more…

Liver patients are at higher risk of clotting than of bleeding

There is a complex imbalance of coagulation factors in the liver patient that is essential to understand for effective management of thrombotic and hemorrhagic events. In general, patients with liver disease are more likely to develop thrombotic disease than they are bleeding diathesis, even if the INR is elevated.

Increased risk of thrombosis: patients with cirrhosis may have decreased protein S and C more so than a reduction in Factors 2, 7, 9, 10 and this would favor thrombosis, rather than bleeding.

Pitfall: a common pitfall is assuming that a liver patient with an elevated INR is protected from thrombotic events. An elevated INR level does not imply that the patient is protected from pulmonary embolism or portal vein thrombosis.

Hypoalbuminemia can be considered a risk factor for thrombosis risk in liver patients

A potential predictor of venous thromboembolism in a cirrhotic patient (assumed to be “auto-anticoagulated” based on an elevated INR value) is serum albumin. It is hypothesized that lower serum albumin concentration is a surrogate for decreased protein synthesis by the liver and thus decreased production of endogenous anticoagulant factors such as Protein C and S. In short, if the albumin is low, the patient may be at increased risk of thromboembolic events.

Treatment of thrombotic liver disease: cirrhotic vs non-cirrhotic

Treatment of thrombotic liver disease varies with the presence or absence of cirrhosis. Cirrhosis increases the risk of catastrophic bleeding from esophageal or gastric varices if the patient is anticoagulated. Patients with cirrhosis who require anticoagulation need careful evaluation with endoscopy for varices and these varices are best definitively treated with banding. Consideration should also be given to clot removal, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt procedure, or surgical shunting as an alternative to anticoagulation.

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT)

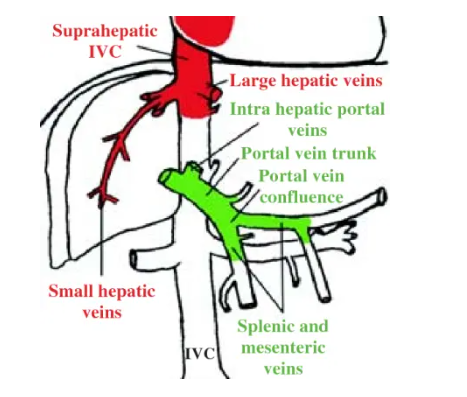

The portal vein is formed from the confluence of splenic and superior mesenteric veins that drain the spleen and small intestines. The occlusion of the portal vein by a thrombus occurs in cirrhotic patients and other patients in a prothrombotic state, such as those with active cancer. Liver disease is a risk factor for venous thromboembolism regardless of the INR level.

Most PVTs are picked up coincidentally, as 20-40% of patients with PVT are asymptomatic, 20-50% present with abdominal pain, and 25-40% present with GI bleed. The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) suggests that we consider acute PVT in “any patient with abdominal pain of more than 24 hours duration,” independent of the presence of fever or ileus.

Physical examination in patients with PVT is highly variable and depends on onset and extension of occlusion. Similarly, laboratory analysis shows a spectrum of non-patterned and non-specific values of CBC and metabolic panel with typically normal transaminase levels, unless an underlying condition such as cirrhotic liver failure or hepatitis is present. Liver function is usually preserved in PVT.

Have a low threshold to obtain imaging for liver patients with abdominal pain or GI bleed to look for PVT. CT with contrast is the imaging modality of choice. Doppler ultrasound is an excellent alternative to CT with a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 92% for portal vein thrombosis.*

*For more information on imaging of portal vein thrombosis, please see The ABCD of portal vein thrombosis: a systematic approach [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-Text PDF]. Radiol Bras. 2020 Nov-Dec; 53(6): 424–429.

Most PVTs are picked up coincidentally, as 20-40% of patients with PVT are asymptomatic, 20-50% present with abdominal pain, and 25-40% present with GI bleed. The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) suggests that we consider acute PVT in “any patient with abdominal pain of more than 24 hours duration,” independent of the presence of fever or ileus.

Physical examination in patients with PVT is highly variable and depends on onset and extension of occlusion. Similarly, laboratory analysis shows a spectrum of non-patterned and non-specific values of CBC and metabolic panel with typically normal transaminase levels, unless an underlying condition such as cirrhotic liver failure or hepatitis is present. Liver function is usually preserved in PVT.

Have a low threshold to obtain imaging for liver patients with abdominal pain or GI bleed to look for PVT. CT with contrast is the imaging modality of choice. Doppler ultrasound is an excellent alternative to CT with a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 92% for portal vein thrombosis.

Management of portal vein thrombosis (PVT) in patients with chronic liver disease

Step 1: evaluate for bleeding risk (eg: gastroesophageal varices)

Step 2: consider prophylactic treatment for variceal bleeding before anticoagulation; if varices are present, initiate treatment with beta blockers and/or arrange for rubber band ligation in patients with large varices or in those with previous variceal bleeding

Step 3: ensure platelets > 50,000 and fibrinogen > 100 mg/dL; may consider vitamin K for bleeding however it often does not result in an improved INR in liver patients

Step 4: start spontaneous bacterial peritonitis prophylaxis – ceftriaxone 1 g IV daily until patient is taking food orally

Step 5: start anticoagulation, preferably in consultation with a hematologist

LMWH: consider using LMWH (as VKA monitoring may be difficult due to variations in INR with cirrhosis and unfractionated heparin is generally not recommended as the baseline PTT is often prolonged) and use fixed or weight-adjusted doses.

Bleeding in the liver patient

Key concept: most life-threatening GI bleeds in liver patients are caused primarily by portal hypertension and only secondarily to altered hemostasis.

Altered hemostasis is multifactorial including decreased platelet count and function, increased fibrinolysis and Vitamin K deficiency. Liver disease impairs factor synthesis, which leads to decreased Vitamin K dependent factors (II, VII, IX, X).

Pitfall: relying on INR, PT, PTT in a cirrhotic patient who is not taking Warfarin to risk stratify for bleeding can be misleading. The INR measures Vitamin K dependent factors, does not reflect the entire coagulation cascade, and its elevation is not necessarily indicative of the need for fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs), as it does not contribute significantly to development of variceal bleeding or other sources of hemorrhage in these patients.

ED management of bleeding in the liver patient

Key concept: do not over transfuse. Carefully weigh the benefits of giving additional blood products in an attempt to optimize coagulopathy against the potential for increasing portal pressure (portal hypertension), especially in a patient with varices, even if this is not the site of acute bleeding.

1.Obtain source control – obtain source control of the bleed; when accomplished rapidly, it may obviate the need for administration of blood products

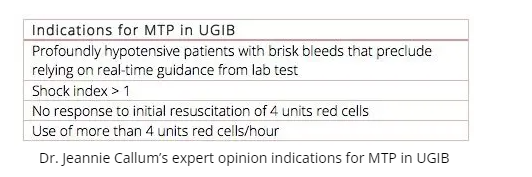

2.Massive transfusion protocol – consider activation of a massive transfusion as per your hospital protocol if the patient is hemorrhaging rapidly. A close look at the TRIGGER Study out of the UK, reveals that only 5% of variceal bleeds require a massive transfusion protocol. In other words, 95% of GI bleed patients require only red cell transfusions. Over-activation of massive transfusion protocols lead to unnecessary

complications such as Transfusion Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO) and wasted blood products.

The Shock Index is Heart Rate/Systolic Blood Pressure

*Reviewing Posts Related To The Shock Index Posted on October 25, 2020 by Tom Wade MD

“The following is from my post above, quoting from Shock Index – A Better Vital Sign in Trauma, [This link is broken] Jan 8, 2012, from The Short Coat blog:

“The gist: Don’t rely on a trauma patient’s normal vital signs to assume they’re hemodynamically stable. Rather, use the shock index (HR/SBP) to predict a patient’s need for massive transfusion. Normal SI = 0.5-0.7”

Andrew Petrosoniak on MTP from EMU

3. Employ TEG or ROTEM to guide management of the bleeding liver patient; if unavailable evaluate platelet count and fibrinogen level. Do not rely on the INR!

- Pool of platelets to maintain a platelet count greater than 50,000 for active, severe, or CNS bleeding. If there is severe ongoing bleeding and platelet function is thought to be impaired, the clinician may consider platelet transfusion independent of platelet count.

- Cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen to maintain a fibrinogen level > 100 mg/dL.

4. Consider Vitamin K – Administer 10 mg of Vitamin K to those at risk of Vitamin K deficiency. Based on expert opinion, it is reasonable to administer Vitamin K in bleeding or non-bleeding liver pts if the INR is greater than 5. However, if the INR is elevated for a reason other than Vitamin K deficiency, then Vitamin K is unlikely to be helpful, and may promote thromboembolic events.

TXA in liver patients with life-threatening bleeding

Start here.