In this post I link to and excerpt from Practical Neurology‘s Infectious Encephalitis: Mimics And Chameleons, [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] Pract Neurol. 2019 Jun;19(3):225-237.

Here are excerpts:

Abstract

‘Query encephalitis’ is a common neurological consultation in hospitalised patients. Identifying the syndrome is only part of the puzzle. Although historically encephalitis has been almost synonymous with infection, we increasingly recognise parainfectious or postinfectious as well as other immune mediated causes. We must also distinguish encephalitis from other causes of encephalopathy, including systemic infection, metabolic derangements, toxins, inherited metabolic disorders, hypoxia, trauma and vasculopathies. Here, we review the most important differential diagnoses (mimics) of patients presenting with an encephalitic syndrome and highlight some

unusual presentations (chameleons) of infectious encephalitis.Introduction

‘Query encephalitis’ is a common reason for neurological consultation in hospitalised patients. Clinically, infectious encephalitis is characterised by acute onset of fever, altered mental status, focal neurological deficits and generalised or focal seizures.1 It can be difficult to identify a specific cause, which remains undetermined in up to half of cases. Historically, encephalitis has been almost synonymous with direct infection, but we now recognise parainfectious or

postinfectious causes, as well as non-infectious causes.It is essential to narrow the differential diagnosis, since starting treatment promptly can improve outcome and avoid unnecessary testing and treatments.

Here we review the most important differential diagnoses (mimics) of patients presenting with an encephalitic syndrome and highlight some unusual presentations (chameleons) of

infectious encephalitis.Infectious encephalitis

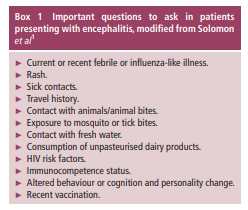

Viruses cause most cases of infectious encephalitis, but bacteria (especially intracellular organisms such as Rickettsiae), fungi and parasites are also important. When evaluating a patient with suspected central nervous system (CNS) infection, it is essential to determine why this individual,

in this place, has developed this disease at this time2

(box 1). Infectious encephalitis can be sporadic, as with herpes simplex virus, or can be epidemic, as with many

arthropod-borne viruses.1 Age, geography, season, immunocompetence and psychosocial factors define the range of potential pathogens. All patients with suspected encephalitis should be tested for HIV, which not only predisposes to CNS infection but itself can cause meningoencephalitis during

primary infection.3Any patient with suspected CNS infection should have a lumbar puncture, unless contraindicated.

Herpes simplex virus encephalitis is the most common cause of sporadic encephalitis. Most cases are caused by herpes simplex virus type 1, but around 10% are caused by type 2.1

The most distinctive presenting features are fever, disorientation, aphasia and behavioural disturbances, and up to a third of patients have convulsive seizures.1Neuroimaging can be negative acutely [of herpes simplex encephalitis], but by 48 hours, over 90% of patients have MR brain imaging abnormalities and sensitivity approaches 100% at 3–10 days.4

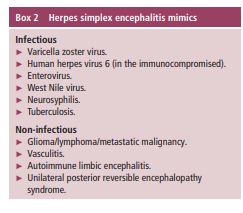

Although fairly characteristic, neuroimaging is not 100% specific, and clinicians should be aware of important imaging mimics (box 2) (figure 1).

CSF herpes simplex virus PCR is both highly sensitive and specific and usually establishes the diagnosis but can be negative if obtained acutely.1 Repeated CSF examination 24–72 hours later is usually diagnostic.

[Please review the complete text on Infectious Encephalitis on pp 225 + 226.]

Neurological conditions that mimic infectious encephalitis

We divide the mimics into parainfectious/postinfectious and non-infectious causes, although there is some overlap. For example, autoimmune encephalitis can be triggered by infection but also occurs with malignancy, and although acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is generally considered to be post-infectious, there is not always an identified definitive infectious trigger.

Parainfectious and postinfectious encephalopathies

ADEM (Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis) and acute hemorrhagic encephalomyelitisADEM is usually a monophasic, inflammatory demyelinating disorder of the CNS. It is more common in children but can occur in all ages.5 It is characterised

by the abrupt onset of neurological symptoms days to weeks following infection or immunisation.5 Although there is not always a clearly identified precipitant, most cases have a non-specific flu-like illness preceding the onset of neurological symptoms.Acute haemorrhagic encephalomyelitis is considered

a hyperacute and more fulminant variant of ADEM.

Like ADEM, it is commonly triggered by infection or vaccination. Brain imaging usually shows haemorrhagic lesions in the white matter.6 CSF examination often shows polymorphonuclear cells as well as numerous red blood cells (in the absence of a traumatic tap).[Please review the complete text on p. 226]

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis syndrome

START REVIEW HERE

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is a syndrome of excessive inflammation due to abnormal immune activation, probably caused by a lack of normal downregulation of activated macrophages and lymphocytes.7

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is a syndrome of excessive inflammation due to abnormal immune activation, probably caused by a lack of normal downregulation of activated macrophages and lymphocytes.7

In patients where neurological findings dominate the clinical picture, infectious encephalitis is likely. In the vast majority of cases, however, neurological symptoms are preceded by weeks of systemic symptoms.

Cytopenias develop in up to 80% of patients. Serum ferritin is commonly elevated up to and above 10 000 µg/L. Liver function abnormalities and associated hypertriglyceridaemia and coagulation abnormalities are very common.

MR brain scan abnormalities are non-specific and include parameningeal infiltration, subdural collections and necrotic changes. Findings consistent with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome are also very common.

The CSF protein is frequently elevated, and half of cases have a lymphocytic pleocytosis.

Histopathology from bone marrow, liver, spleen or lymph nodes may show haemophagocytosis.

Elevated soluble CD25 (soluble interluekin-2 receptor alpha) and reduced natural killer cell function support the diagnosis but may be available only at specialty laboratories.

Influenza-related encephalopathy/encephalitis and acute necrotising encephalopathy

Influenza-related encephalitis/encephalopathy is a rapidly progressive encephalopathy that develops days after the onset of the first symptoms of influenza.8 Its pathophysiology remains unclear, and neither direct viral infection of the CNS nor a postinfectious inflammatory process appears to cause the condition. CSF studies are often normal, although a small number of cases have elevated CSF protein or mild pleocytosis.

Similarly, there is only rarely any direct evidence of viral invasion on CSF and histopathology. The disease tends to affect children younger than 5 years of age, but there have been isolated cases in adults.8 9Cerebral malaria

Cerebral malaria is a clinical syndrome defined as an

otherwise unexplained encephalopathy in patients with malaria parasitaemia. It is almost always associated with Plasmodium falciparum infection. Risk factors include young age, pregnancy, HIV seropositivity and splenectomy.11 In adults, cerebral malaria is more common in non-immune individuals than those living in endemic areas.11 Cerebral malaria should be

suspected in travellers returning from endemic regions who present with unexplained fever, even if they have been taking antimalarial prophylaxis.Clinically, it presents with a prodrome of irregular fevers, malaise, abdominal pain, headache, anorexia, vomiting followed by encephalopathy, seizures and coma.

In adults, neurological symptoms develop 7 days after symptom onset and rapidly evolve to coma. There are often signs of brainstem dysfunction.*

*See Brainstem dysfunction in critically ill patients [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Download Full Text PDF]. Crit Care. 2020 Jan 6;24(1):5.

CSF is usually normal or near normal. Associated haematological and metabolic abnormalities such as hypoglycaemia, anaemia, thrombocytopenia and acidosis are common.

The diagnosis is made by examining thick and thin blood films, which may be negative initially especially in those who have been taking antimalarial prophylaxis.

Non-infectious encephalitis

Autoimmune encephalitis associated with paraneoplastic or neuronal surface antibodiesStart here.