In this post, I link to and excerpt from The Curbsiders‘ [Link is to the full episode list] #350 Rapid Response Series: Acute Hypoxemia [Diagnosing & Managing Acute Hypoxemia with Nick Mark MD], By

All that follows is from the above resource.

Transcript-The-Curbsiders-#350-Hypoxemia.docx

Quick! Your patient is desaturating! Have no fear, for in this installment of our Rapid Response series we have recruited pulmonologist/intensivist extraordinaire, the great Dr. Nick Mark of ICU One Pager, to share with us all the pitfalls and pearls we need to have under our collective belt when it comes to understanding, managing, and considering the etiologies of acute hypoxemia!

Free CME for this episode at curbsiders.vcuhealth.org!

Show Segments

- Intro, disclaimer, guest bio

- Guest one-liner, Picks of the Week

- Case from Kashlak; Definitions

- How does a pulse oximeter work?

- Clinical approach to hypoxemia

- The SIX causes of hypoxemia

- Delivering supplemental oxygen

Acute Hypoxemia Pearls

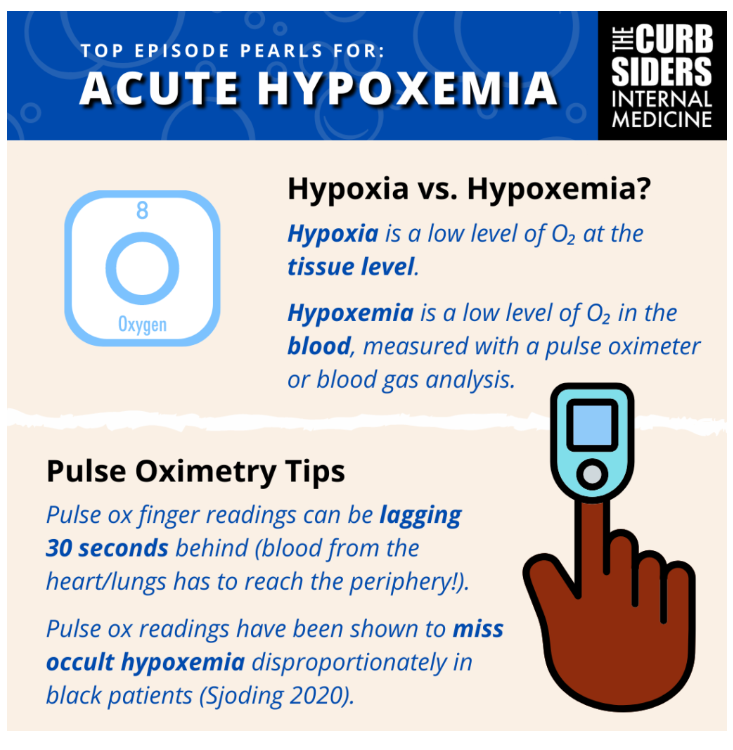

- Hypoxemia refers to low oxygen content in the blood, however, what’s more clinically relevant is hypoxia which suggests reduced oxygen delivery and consequently, inadequate oxygen at the tissue-level, which can result in end-organ dysfunction/damage.

- Pulse oximeters are imperfect tools – interpret the results with caution! Similarly, blood gasses are helpful and have their place… in the right clinical scenario. Not every patient needs an ABG or VBG if they are hypoxemic!

- First question when dealing with hypoxemia: Sick or not sick? That will guide your approach. Next, use history, exam, labs/rads and POCUS to help further evaluate your patient.

- … BUT, treat the patient first! There is no reason NOT to put the patient on supplemental oxygen while performing your evaluation. In fact, it can be therapeutic AND diagnostic!

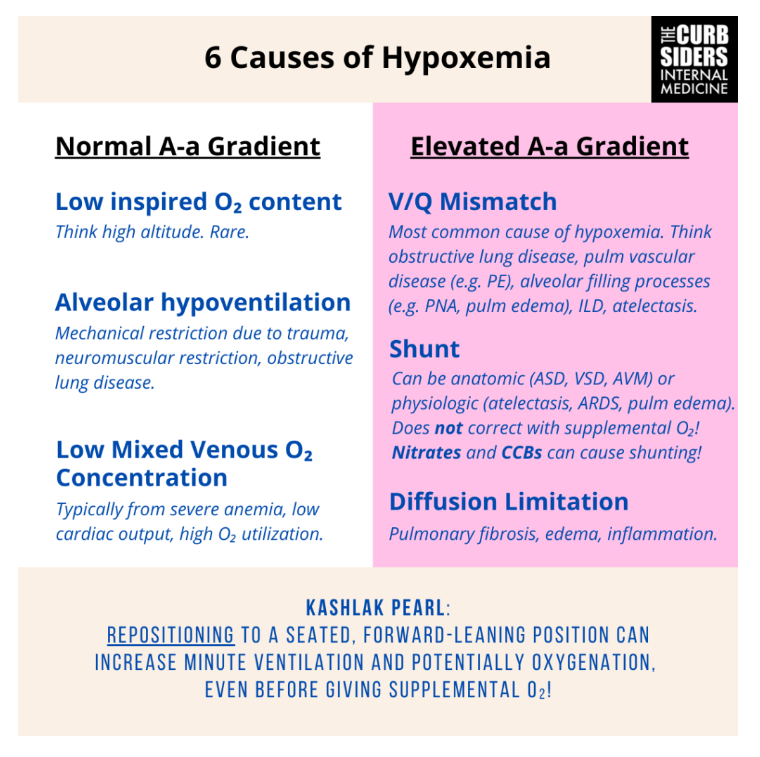

- Remember the SIX major causes for hypoxemia. Shunt, V/Q mismatch and diffusion limitation feature reductions in the A-a difference. All causes of hypoxemia will correct – at least to some degree – with supplemental oxygen, EXCEPT SHUNTING!

- Supplemental oxygen is a powerful treatment modality with many delivery systems – be familiar with the options and indications!

Clinical Approach

- Dr. Mark walks us through a few important, initial considerations:

- Sick or not-sick? This is the first thing to assess ASAP! Red flags:

- Use of accessory muscles?

- Tripod-ing?

- Speaking in short (3-4 word) sentences?

- Altered mental status?

- Inability to protect the airway? (i.e. significant clinical concerns that the patient could have a major aspiration event or similar resulting in decompensation)

- How hypoxemic is the patient?

- An oxygen saturation of 88% is much more reassuring and may afford more time than an oxygen saturation of 68%

- Confirm pulse oximeter is on the patient appropriately with a good wave form

- Pulse oximeter pulse should equal the telemetry pulse reading if patient is on telemetry, and there should be minimal, if any, artifact

- Pulse oximeter should be firmly/appropriately attached (finger tip, toe, ear lobe, forehead)

- Is there evidence of hypoxia? Examples:

- Lactate elevation?

- Altered mental status?

- Chest pain?

- Secondary considerations and further investigation:

- Review the chart, talk to the bedside care team (nurse, tech, etc.) and talk to the patient

- New medications?

- IV fluids are medications and can cause hypoxemia!

- Recent surgeries / procedures?

- Time course?

- In’s and out’s?

- Again, speaks to fluids and possible pulmonary edema –> hypoxemia

- Evaluation

- Examine the patient

- A stethoscope exam can be helpful to identify absent breath sounds or major adventitious sounds but, unfortunately is often not terribly helpful

- Ultrasound can be very helpful, and Dr. Mark assures us that we don’t need to be expert sonographers to make some assessments!

- B-Lines (i.e. comet tails, shimmering lines that spread outward from the probe-head / perpendicular to the pleural surface) are suggestive of pulmonary edema when 3 or more are present in a visual field [Dietrich 2016]

- Can also identify absence of “lung-sliding” which may indicate a pneumothorax (to be followed up by a chest X-ray if immediate action is not necessary) or a large pleural effusion.

- Don’t just look at the lungs! Remember that oxygen delivery requires cardiac output, therefore, a global/general assessment of cardiac function can be helpful.

- A quick look at the RV can be helpful as well – a huge/overriding RV can be suggestive of a pulmonary embolism.

- A quick look at the IVC or jugular veins can HINT at volume status (along with an exam for peripheral edema) .

- Tests

- Chest X-ray can be helpful in getting a bedside, global assessment of the lungs.

- Basic blood work: CBC, BMP can help hone your differential diagnosis (anemia? Renal failure contributing to volume retention?). A point-of-care lactate can help assess for evidence of tissue hypoxia.

- Blood gas: In more challenging cases, a blood gas can be helpful in determining the cause for hypoxemia or to assess for a concurrent ventilatory deficit. A venous blood gas may be sufficient in some cases, or consider an arterial blood gas when the additional information is helpful.

- Troponin, BNP, EKG: Additional tests which may be helpful in the appropriate setting (i.e. patient with chest pain, telemetry changes).

- Dr. Mark reminds us that, in general, the approach to these patients is to attempt to correct hypoxemia via supplemental oxygen before embarking on a hunt for the underlying cause – especially if the patient is symptomatic.

So… what causes hypoxemia? The SIX causes!

- After stabilization, it’s important to have a framework for the causes of hypoxemia. Dr. Mark runs through these as follows, and then discusses an approach.

- Low inspired oxygen content – typically seen at altitude… typically not terribly relevant in most clinical settings.

- Alveolar Hypoventilation – you’ve got to breathe to get oxygen into your lungs!

- Mechanical restriction due to trauma – mostly due primarily to pain

- Neuromuscular restriction – typically not acute

- Obstructive lung disease –> airflow limitation

- Low Mixed Venous Oxygen Concentration

- Venous blood returning to right-heart is extremely low in oxygen content, thus even normal pulmonary physiology is insufficient to supply enough oxygen to incoming blood to result in normal arterial oxygen content

- Causes: Severe anemia, low cardiac output, extremely high oxygen utilization

- V/Q Mismatch – imbalance between perfusion and ventilation

- Most common cause for hypoxemia

- Obstructive lung disease, pulmonary vascular disease (ex: pulmonary embolism), alveolar filling processes (ex: pneumonia, pulmonary edema), interstitial lung disease, atelectasis

- Shunt – Blood passes from right heart to left heart without adequate oxygenation

- Anatomic shunts: ASD, VSD, AVM

- Physiologic shunts: atelectasis, ARDS, pulmonary edema

- Note: atelectasis, alveolar filling processes can contribute to hypoxemia through both shunting and V/Q mismatch

- Shunting does NOT correct with supplemental oxygen!

- Pearl! – Dr. Mark shares with us that shunt can be iatrogenic. Nitrates and calcium channel blockers which cause systemic vasodilation, do not spare the pulmonary vasculature and thus, in some patients, can result in the shunting of blood towards areas of the lung that are less effective gas-exchange, resulting in hypoxemia.

- Diffusion Limitation – impairment in alveolar-capillary interface, minimally present at rest, much more noticeable during exertion/stress

- Pulmonary fibrosis, edema, inflammation

- How can we sort these? The A-a gradient (or A-a difference, since it’s not really a gradient!)*

- This is measured via an arterial blood gas and tells us the difference between alveolar oxygen tension PAO2 and arterial oxygen tension PaO2.

- Normal A-a gradient: Low inspired oxygen content, hypoventilation, low mixed venous oxygen content

- Elevated A-a gradient: Pulmonary cause for hypoxemia – V/Q mismatch, shunt or diffusion limitation

*A-a Gradient Calculator at mdcalc.com

Kashlak Pearl: Check out Dr. Mark’s infographic from his site, ICU OnePager for more!

Supplemental Oxygen

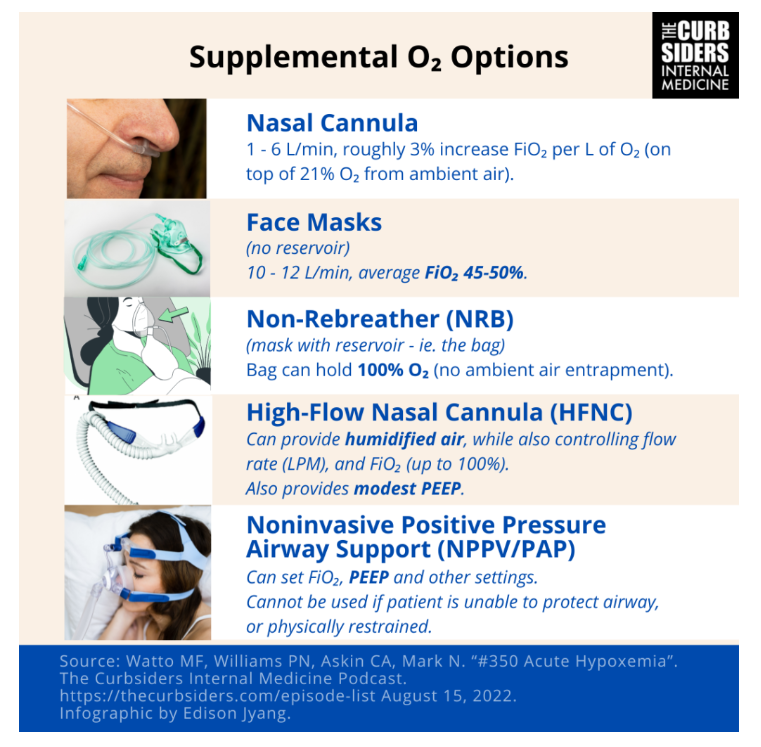

- Nasal Cannulas:

- Come in various “flavors” but generally provide minimal oxygen support

- 1-6 LPM, which provides roughly a 3% FiO2 bump per L of oxygen

- Why? This is because patient’s entrain A LOT of ambient air around the prongs, resulting in a mixture of 100% oxygen from the cannula and 21% oxygen from ambient air.

- Face Masks:

- Different brands, no “reservoir.”

- Typically can provide up to 10 or even 12 LPM of flow, increasing the average FiO2 the patient receives to around 45-50%.

- Non-Rebreather (NRB):

- Mask with a “reservoir” – i.e. the bag.

- The bag holds 100% oxygen, minimizing the entrainment of ambient air, allowing the patient to breath close to 100% oxygen.

- The bag must be full in order for this to work!

- High-flow Nasal Cannula (HFNC):

- Usually provides humidified air, allowing the clinician to select a flow rate (LPM) and an FiO2.

- Flow can be anywhere from 10-60 LPM depending on the device, with an FiO2 that can be set up to 100%.

- FLORALI Trial: HFNC is as effective as NRB and PAP therapy in pure hypoxic respiratory failure with regards to reducing need for intubation, and use was associated with significantly less 90-day mortality.

- HFNC does provide some modest PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure) which can help in hypoxemia.

- Noninvasive positive airway pressure support (PAP)

- Different settings and interfaces (mask types)

- Allows clinician to set FiO2, PEEP and other settings to achieve oxygenation goals

- PEEP stents the airways/alveoli open, allowing for more effective gas exchange.

- Bi-level settings can decrease work of breathing.

- May not be well-tolerated in certain patients.

- Classically, may be used as a bridge while awaiting the results of an intervention or as a bridge to intubation.

- Example: providing PAP after giving furosemide in a case of cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

- Note: Dr. Mark informs us that furosemide, and other loops, act as venodilators and thus, you can see a positive effect on oxygenation PRIOR to an increase in urine output!

- CANNOT be used if a patient is unable to protect their airway (i.e. risk for vomiting and/or aspiration).

- DO NOT use with restrained patients.

Kashlak Pearl: Hypoxemia can also be combated, in part, by good positioning, Getting your patient into a seated/forward-leaning position can help offload the chest wall and put them in a position where they can increase their minute ventilation and potentially improve oxygenation, even before placing a nasal cannula or other device.

For more information, Dr. Mark has a OnePager on nasal oxygenation devices and PAP therapy.