The following is a link to the complete post of Pediatric Rash BY DR SEAN FOX · PUBLISHED OCTOBER 16, 2015 · UPDATED FEBRUARY 6, 2016 from his outstanding blog Pediatric EM Morsels.

And because these posts are really just my study notes, I’ve included a fair amount of extra links and info from other resources.

It is also a great idea to type “pediatric rash” in the search box of Pediatric EM Morsels [link is to the Pediatric EM Morsels search on the topic]. There you will find links to 29 pages of outstanding posts on pediatric dermatology from Dr. Fox.

Dr. Fox’s approach to every pediatric rash is as follows:

Pediatric Rash – Step 1: Sick or Not Sick (meaning is the child unwell [“sick”]* or well [“not sick” as defined by the Royal Children’s Hospital of Melbourne Clinical Practice Guidelines below)?

Is the child unwell?* If yes, initiate immediate treatment.

*The following definition of unwell is from the RCHM Guideline on petechiae and purpura (but the definition can be used in every infant or child you are evaluating for any complaint):

Children should be considered unwell when they have the following features:

Abnormal vital signs

- Tachycardia

- Tachypnoea and or desaturation in air

- Increasing systolic to diastolic difference in blood pressure (ie widened pulse pressure)

Poor peripheral perfusion

- Cold extremities

- Prolonged capillary refill

Altered conscious state

- Irritability (inconsolable crying or screaming)

- Lethargy (including as reported by family or other staff)

Pediatric Rash – Step 2: Does the rash have “badness” meaning characteristics of the rash that can be a signal for a serious illness?

Look for the following rash characteristics that suggest potentially serious illness:

- Petechiae

- immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) [link is to Dr. Fox’s post on this disease]

- See also Clinical Practice Guideline From the Royal Children’s Hospital of Melbourne (RCHM), Fever and petechiae – Purpura

- Meningococcemia [link is to Dr. Fox’s post, Meningococcemia and petechiae].

- Leukemia [Link is to Dr. Fox’s post Leukemia Clues

PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 30, 2016]- Childhood leukemia can present with pallor, petechiae, purpura, or bruising.

- Purpura

- Henoch Schonlein Purpura [link is Dr. Fox’s post]

- See also Clinical Practice Guideline From RCHM, Henoch-schonlein purpura

- Platelet Disorders, TTP [Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia – link is from the emedicine.medscape article. Note that TTP can also cause petechiae

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

- Background, Physical Exam, Laboratory Studies, DIC Scoring Systems [All these links are to the DIC article in emedicine/medscape.com]

- Child Abuse [Link is to Dr. Fox’s post]

- See also Which injuries may indicate child abuse? [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2010 Dec;95(6):170-7. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.170431. Epub 2010 Oct 6.

- Leukemia [Link is to Dr. Fox’s post Leukemia Clues

PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 30, 2016]- Childhood leukemia can present with pallor, petechiae, purpura, or bruising.

- Henoch Schonlein Purpura [link is Dr. Fox’s post]

- Vesicles

- HSV [Link is to Dr. Fox’s post Neonatal HSV]

- Chickenpox [See Pediatric Chickenpox Updated: Aug 04, 2017 from emedicine.medscape.com]

- The following is from What Causes Vesicles?, Posted on March 2, 2015 from the blog Pediatric Education:

Vesicles are circumscribed, elevated, fluid-filled lesions < 1 cm on the skin. They contain serious exudates or a mixture of blood and serum. They last for a short time and either break spontaneously or evolve into bullae. They can be discrete (e.g. varicella or rickettsial disease), grouped (e.g. herpes), linear (e.g. rhus dermatitis) or irregular (e.g. coxsackie) in distribution.

Associated symptoms such as pruritus, fever, myalgias, coryza and cough, along with a history of potential contact can be helpful. Vesicular rashes that are associated with systemic findings such as fever are usually due to infectious diseases (especially viruses and bacteria), while those that do not have systemic findings often are due to contact or infectious diseases that are non-respiratory contacts such as scabies or tinea.

Most patients do not need specific testing as the clinical history and physical examination will often be enough. In certain cases, scraping of the lesion to look for parasites (i.e. scabies) or multinucleated giant cells (i.e. herpes) or fungus may be indicated.

Most treatment is supportive. Topical agents such as calamine lotion or oatmeal baths may provide some relief. Medication for pain and pruritus can be helpful. Treatment for specific diseases such as acyclovir for herpes, antibiotics for bacterial disease and antifungal mediation for fungal diseases should be recommended as appropriate.

Vesicular or bullous exanthems should be investigated more extensively if there is skin sloughing, petechiae or purpura, fever and irritability, inflammation of the mucosa, urticaria, has respiratory distress, and diarrhea or abdominal pain.

The differential diagnosis for vesicular exanthems includes:

- Viral

- Coxsackie

- Echo

- Herpes

- Smallpox

- Varicella

- Bacteria

- Haemophilus

- Staphylococcus

- Streptococcus

- Mycoplasma

- Fungal

- Trichophyton mentagrophytes

- Tricophyton rubrum

- Parasitic

- Rickettsial diseases

- Scabies

- Tularemia

- Other

- Contact and Rhus dermatitis

- Dishidrotic eczema

- Kawasaki disease

- Photosensitivity

- Bullae: What follows is from What Causes Bullae?, Posted on April 20, 2015 of the blog Pediatric Education:

Bullae are fluid-filled epidermal lesions that are filled with serous or seropurulent fluid. They are > 1 cm in diameter and often easily rupture due to their thin walls. The differential diagnosis is different for bullae than for vesicular lesions with bullae being often more worrisome. However there is overlap and vesicular diseases can become large enough to be bullae. Drug toxicity and genetic problems are also more common in bullae whereas vesicles are more often caused by infectious diseases.

The differential diagnosis of bullae is

- Trauma

- Burns – including sunburn

- Frostbite

- Stings

- Infection

- Impetigo and Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

- Herpes

- Meningococcemia

- Orf

- Syphilis

- Genetic

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica

- Epidermolysis bullosa

- Incontinentia pigmenti

- Porphyria

- Other

- Bullous disease of childhood

- Drugs

- Lupus erythematosis

- Toxic epidermal necrolysis syndrome (TEN syndrome)

- Pemphigus

- Stevens Johnson syndrome

- Target Lesions [Link is to Erythema Multiforme in Children

BY DR SEAN FOX · PUBLISHED MAY 5, 2017 from Pediatric EM Morsels]- See Erythema Multiforme from emedicine.medscape.com:

- Erythema Marginatum

- See Acute Rheumatic Fever – Don’t Forget about it!BY DR SEAN FOX · PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 2, 2011 · UPDATED JULY 3, 2015 from Pediatric EM MorselsSee

- Acute Rheumatic Fever with Erythema Marginatum [Outstanding pictures and clinical case and description of w/u of ARF) N Engl J Med 2016; 375:2480December 22, 2016DOI: 10.1056/NEJMicm1601782.

- See the above article’s additional images of Erythema Marginatum in the Supplementary Appendix

- Urticaria

- Anaphylaxis [link is to Dr. Fox’s post on the subject]

- Serum Sickness [link is to Dr. Fox’s post on the subject]

- Angioedema

- What follows is from Angioedema Updated: Apr 12, 2017

from emedicine.medscape.com:

- What follows is from Angioedema Updated: Apr 12, 2017

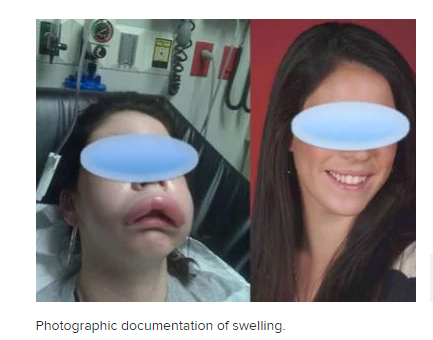

Angioedema is the swelling of deep dermis, subcutaneous, or submucosal tissue due to vascular leakage. [1, 2] Acute episodes often involve the lip, eyes, and face (see the image below); however, angioedema may affect other parts of body, including respiratory and gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa. Laryngeal swelling can be life-threatening.

Diagnostic Considerations from the above emedicine.medscape article:

Special consideration should be given to those who experience angioedema without urticaria. In such cases, hereditary and acquired angioedema (AAE) must be differentiated. [14]

When angioedema is associated with urticaria, the diagnostic algorithm is almost identical to that of urticaria patients. [That is be alert for anaphylaxis and serum sickness (links are to Dr. Fox’s posts on these subjects)].For recurrent angioedema without urticaria, it is strongly recommended to rule out hereditary angioedema (HAE), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor induced angioedema (ACEI-AAE, or AIIA), and acquired C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency angioedema (C1-INH-AAE). [49]

Except for ACEI-AAE (or AIIA), C1-INH-AAE, and different types of HAE, a significant proportion of angioedema can be adequately controlled with daily doses of nonsedating antihistamines. [14] Therefore, for angioedema without urticaria, and once C1 INH deficiency and ACEI-AAE are ruled out, empirical treatment with high doses of a second generation antihistamine (up to 4 times more than the conventional dose) can help further categorize the patients (histaminergic vs. nonhistaminergic).

- Desquamation

- Staph Scalded Skin Syndrome [Link is to Dr. Fox’s post]

- Kawasaki Disease [Link is to Dr. Fox’s post]

- If none of the “signs of badness” of step 2 are present, then we proceed to Dr. Fox’s step 3.

Pediatric Rash – Step 3: Look at the mucous membranes again:

- Let’s be honest, looking in a kid’s mouth can be challenging, but this step is very important!

- For instance, ITP with Wet Purpura (mucous membrane involvement) may be a clue to greater risk of spontaneous bleeding.

- Certainly, finding Koplick’s Spots would alter your plans.

- Even finding herpangina or gingivostomatits may impact your plan!

- While wiping the sweat off of your brow and allowing the parent’s muscle fatigue to resolve, move onward to step 4.

Pediatric Rash – Step 4: Look for “Common Pediatric Rashes:

- Now, you get to demonstrate your Pediatric Rash Prowess by looking for those “classic” pediatric skin eruptions.

- Molluscum

- Pityriasis Rosea

- Erythema infectiosum

- Perianal Strep

- Impetigo and Bullous Impetigo

- Intertrigo

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Morbilliform [I added this and the link to Dr. Fox’s list. See also Viral exanthems for more on viral rashes]

- Scarlatiniform

- Popsicle Panniculitis

- Hand-Foot-Mouth Disease

- Scabies

- Diaper Dermatitis and Fungal Infection?

- If Steps 1-4 have not lead to a diagnosis or a high level of concern, then move onward to step 5.

Pediatric Rash – Step 5: Admit You Aren’t Sure:

- This is the hardest part… admitting to the family that you are not sure what the cause of the rash is can be challenging.

- We are not admitting defeat… we are appropriately avoiding the addition of an incorrect “label” (diagnosis) to the patient.

- Announce your reassurance in the lack of the concerning characteristics…

- Acknowledge that rashes often evolve over time…

- In the next several hours to days, your ability to make a more accurate diagnosis may change.

- Give good anticipatory guidance on what specific things they need to monitor for and encourage repeat evaluation in the next 12-24 hours.