8. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment Diabetes Care 2017;40(Suppl. 1):S64–S74 | DOI: 10.2337/dc17-S011

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY FOR TYPE 2 DIABETES

The use of metformin as first-line therapy was supported by findings from a large meta-analysis, with selection of second-line therapies based on patient-specific considerations (20).

The following text is from p S66 of Reference (2).

Initial Therapy

Metformin monotherapy should be started at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes unless there are contraindications. Metformin is effective and safe, is inexpensive, and may reduce risk of cardiovascular events and death (22). Metformin may be safely used in patients with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) as low as 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (23), and the U.S. label for metformin was recently revised to reflect its safety in patients with eGFR >/= 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (24). Patients should be advised to stop the medication in cases of nausea, vomiting, or dehydration. Metformin is associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, with a recent report from the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study (DPPOS) suggesting that periodic testing of vitamin B12 levels should be considered in metformin-treated patients, especially in those with anemia or peripheral neuropathy (25).

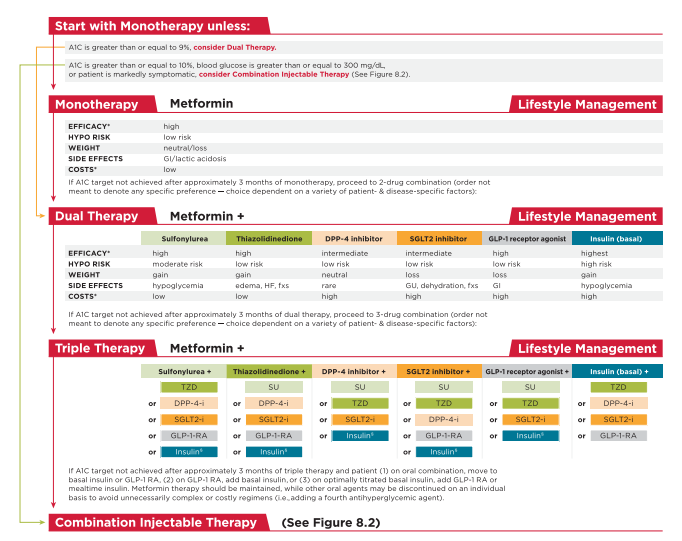

In patients with metformin contraindications or intolerance, consider an initial drug from another class depicted in Fig. 8.1 under “Dual Therapy” and proceed accordingly. When A1C is $9% (75 mmol/mol), consider initiating dual combination therapy (Fig. 8.1) to more expeditiously achieve the target A1C level. Insulin has the advantage of being effective where other agents may not be and should be considered as part of any combination regimen when hyperglycemia is severe, especially if symptoms are present or any catabolic features (weight loss, ketosis) are present. Consider initiating combination insulin injectable therapy (Fig. 8.2) when blood glucose is > or/= to 300 mg/dL (16.7 mmol/L) or A1C is > or/= to 10% (86 mmol/mol) or if the patient has symptoms of hyperglycemia (i.e., polyuria or polydipsia). As the patient’s glucose toxicity resolves, the regimen may, potentially, be simplified.

The following is from p S66 of Resource (2)

The following text is from pp S66 + 67, S70 of Resource (2)

Combination Therapy

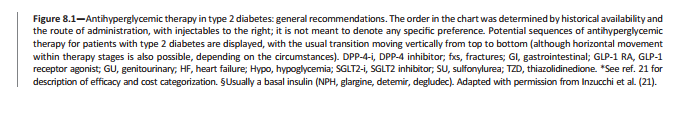

Although there are numerous trials comparing dual therapy with metformin alone, few directly compare drugs as add-on therapy. A comparative effectiveness metaanalysis (23) suggests that each new class of noninsulin agents added to initial therapy generally lowers A1C approximately 0.9–1.1%. If the A1C target is not achieved after approximately 3 months, consider a combination of metformin and one of the six available treatment options: sulfonylurea, thiazolidinedione, DPP-4 inhibitor, SGLT2 inhibitor, GLP-1 receptor agonist, or basal insulin (Fig. 8.1). If A1C target is still not achieved after ;3

months of dual therapy, proceed to three-drug combination (Fig. 8.1). Again, if A1C target is not achieved after ;3 months of triple therapy, proceed to combination injectable therapy (Fig. 8.2).Drug choice is based on patient preferences (26), as well as various patient, disease, and drug characteristics, with the goal of reducing blood glucose levels while minimizing side effects, especially hypoglycemia. Table 8.1 lists drugs commonly used in the U.S. Cost-effectiveness models have suggested that some of the newer agents may be of relatively lower clinical utility based on high cost and moderate glycemic effect (27). Table 8.2 provides cost information for currently approved noninsulin therapies. Of note, prices listed are average wholesale prices (AWP) and do not account for discounts, rebates, or other price adjustments often involved in prescription sales that affect the actual cost incurred by the patient. While there are alternative means to estimate medication prices, AWP was utilized to provide a comparison of list prices with the primary goal of highlighting the importance of cost considerations when prescribing antihyperglycemic treatments. The ongoing Glycemia Reduction Approaches in Diabetes: A Comparative Effectiveness Study (GRADE) will compare four drug classes (sulfonylurea, DPP-4 inhibitor, GLP-1 receptor agonist, and basal insulin) when added to metformin therapy over 4 years on glycemic control and other medical, psychosocial, and health economic outcomes (28).

Rapid-acting secretagogues (meglitinides) may be used instead of sulfonylureas in patients with sulfa allergies, irregular meal schedules, or those who develop late postprandial hypoglycemia when taking a sulfonylurea. Other drugs not shown in Fig. 8.1 (e.g., inhaled insulin, a-glucosidase inhibitors, colesevelam, bromocriptine, and pramlintide) may be tried in specific situations but are not often used due to modest efficacy in type 2 diabetes, the frequency of administration, the potential for drug interactions, and/or side effects.

Resources:

(1) CONSENSUS STATEMENT BY THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGISTS AND AMERICAN COLLEGE OF ENDOCRINOLOGY ON THE COMPREHENSIVE TYPE 2 DIABETES MANAGEMENT ALGORITHM – 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Endocr Pract. 2017 Feb;23(2):207-238. doi: 10.4158/EP161682.CS. Epub 2017 Jan 17.

(2) AMERICAN DIABETES ASSOCIATION STANDARDS OF MEDICAL CARE IN DIABETES—2017 [Full Text PDF]. January 2017 Volume 40, Supplement 1.

(3) Patient-directed titration for achieving glycaemic goals using a once-daily basal insulin analogue: an assessment of two different fasting plasma glucose targets – the TITRATETM study [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009 Jun;11(6):623-31. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01060.x.