As I remind occasional visitors, this blog is simply my medical study notes. And today, I’m reviewing acute liver failure following a recent review of Episodes #100 and #101 on cirrhosis from The Curbsiders (as usual both were outstanding podcasts and the show notes were also, as usual, outstanding – thanks, Curbsiders [this link is to the Curbsiders bio page]).

The American Association For The Study Of Liver Diseases [AASLD] has published the AASLD Position Paper: The Management of Acute Liver Failure: Update 2011 [Link is to the 88 page enhanced PDF].

Our obligation as physicians is to recognize Acute Liver Failure at the earliest opportunity, stabilize the patient, and contact and arrange for safe transport to a liver transplant center.

Here are the first two recommendations with the rationales from the above reference:

RECOMMENDATION 1

Patients with acute liver failure (ALF) should be hospitalized and monitored frequently, preferably in an ICU (III).RATIONALE 1

Acute liver failure often affects young persons and carries a high morbidity and mortality. Prior to transplantation, most series suggested less than 15% survival. Currently, overall short-term survival (one year) including those undergoing transplantation is greater than 65%.7RECOMMENDATION 2

Contact with a transplant center and plans to transfer appropriate patients with ALF should be initiated early in the evaluation process (III).RATIONALE 2

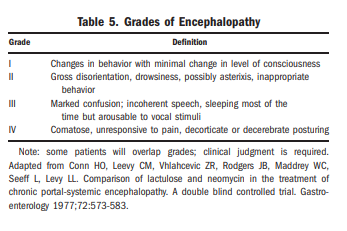

All patients with clinical or laboratory evidence of acute hepatitis should have immediate measurement of prothrombin time and careful evaluation for subtle alterations in mentation. If the prothrombin time is prolonged by ∼4-6 seconds or more (INR ≥1.5) and there is any evidence of altered sensorium, the diagnosis of ALF is established and hospital admission is mandatory. Since the condition may progress rapidly, patients determined to have any degree of encephalopathy should be transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) and contact with a transplant center made to determine if transfer is appropriate. Transfer to a transplant center should take place for patients with grade I or II encephalopathy (Table 5) because they may worsen rapidly. Early transfer is important as the risks involved with patient transport may increase or even preclude transfer once stage III or IV encephalopathy develops.CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

Cerebral edema and intracranial hypertension (ICH) have long been recognized as the most serious complications of acute liver failure.83 Uncal herniation may result and is uniformly fatal. Cerebral edema may also contribute to ischemic and hypoxic brain injury, which may result in long-term neurological deficits in survivors.84 The pathogenic mechanisms leading to the development of cerebral edema and intracranial hypertension in ALF are not entirely understood. It is likely that multiple factors are involved, including osmotic disturbances in the brain and heightened cerebral blood flow due to loss of cerebrovascular autoregulation. Inflammation and/or infection, as well as factors yet unidentified, may also contribute to the phenomenon.85 Several measures have been proposed and used

with varying success to tackle the problem of cerebral edema and intracranial hypertension in patients with ALF. Interventions are generally supported by scant evidence; no uniform treatment protocol has been established.

Because the clinician outside of the transplant center will immediately contact the transplant center for management guidance and for transfer arrangements, supportive care of the patient while awaiting transfer would be given in consultation with the receiving transplant center.

What follows are excerpts from Resource (2) Introduction to the Revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Position Paper on Acute Liver Failure 2011:

Introduction

The diagnosis of ALF hinges on identifying that the patient has an acute insult and is encephalopathic. Imaging in recent years has suggested ‘‘cirrhosis,’’ but this is often an overcall by radiology, because a regenerating massively necrotic liver will give the same nodular profile as cirrhosis.1 It is vital to promptly get viral hepatitis serologies, including A-E as well as autoimmune serologies, because these often seem to be neglected at the initial presentation. Fulminant Wilson’s disease can be diagnosed most effectively not by waiting for copper levels (too slow to obtain) or by obtaining ceruloplasmin levels (low in half of all ALF patients, regardless of etiology), but by simply looking for the more readily available bilirubin level (very high) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP; very low), such that the bilirubin/ALP ratio exceeds 2.0.2 The availability of an assay that measures acetaminophen adducts has been used for several

years as a research tool and has improved our clinical recognition of acetaminophen cases when the diagnosis is obscured by patient denial or encephalopathy.3 Any

patient with very high aminotransferases and low bilirubin on admission with ALF very likely has acetaminophen overdose, with the one possible exception being those patients who enter with ischemic injury. Obtaining autoantibodies should be routine and a low threshold for biopsy in patients with indeterminate ALF should be standard, given that autoimmune hepatitis may be the largest category of indeterminate, after

unrecognized acetaminophen poisoning.4

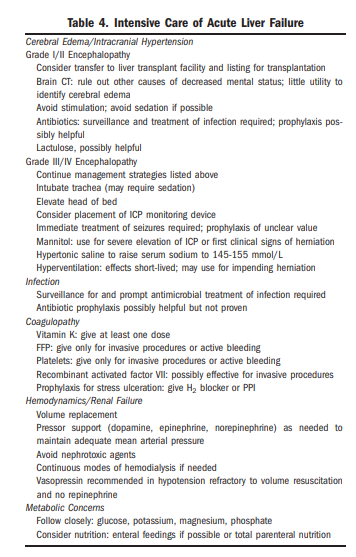

For a review of the likely treatments for acute liver failure, see Table 4 in the enhanced PDF.

Here is Table 4 from the article PDF:

And [note to myself] remember that diagnosis of Acute Liver Failure is not complex — Review Recommendation 2 and Rationale 2 above.

And here is Table 5 from the article PDF:

What follows are excerpts from Resource (2) Introduction to the Revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Position Paper on Acute Liver Failure 2011:

Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a rare condition in which rapid deterioration of liver function results in altered mentation and coagulopathy in individuals without known pre-existing liver disease. U.S. estimates are placed at approximately 2,000 cases per year.4,5 A recent estimate from the United Kingdom was 1-8 per million population.6 The most prominent causes include drug-induced liver injury, viral hepatitis, autoimmune liver disease and shock or hypoperfusion; many cases (15%) have no discernible cause.7 Acute liver failure often affects young persons and carries a high morbidity and mortality. Prior to transplantation, most series suggested less than 15% survival. Currently, overall short-term survival (one year) including those undergoing transplantation is greater than 65%.7 Because of its rarity, ALF has been difficult to study in depth and very few controlled therapy trials have been performed. As a result, standards of intensive care for this condition have not been established although a recent guideline provides some general directions.8

Definition

The most widely accepted definition of ALF

includes evidence of coagulation abnormality, usually an International Normalized Ratio (INR) 1.5, and any degree of mental alteration (encephalopathy) in a patient without preexisting cirrhosis and with an illness of <26 weeks’ duration.9 Patients with Wilson disease, vertically-acquired hepatitis B virus (HBV), or autoimmune hepatitis may be included in spite of the possibility of cirrhosis if their disease has only been recognized for <26 weeks. A number of other terms have been used for this condition, including fulminant hepatic

failure and fulminant hepatitis or necrosis. ‘‘Acute liver failure’’ is a better overall term that should encompass all durations up to 26 weeks.Diagnosis and Initial Evaluation

All patients with clinical or laboratory evidence of acute hepatitis should have immediate measurement of prothrombin time and careful evaluation for subtle alterations in mentation. If the prothrombin time is prolonged by 4-6 seconds or more (INR 1.5) and there is any evidence of altered sensorium, the diagnosis of ALF is established and hospital admission is

mandatory. Since the condition may progress rapidly, patients determined to have any degree of encephalopathy should be transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) and contact with a transplant center made to determine if transfer is appropriate. Transfer to a transplant center should take place for patients with grade I or II encephalopathy (Table 5) because they may worsen rapidly. Early transfer is important as the risks

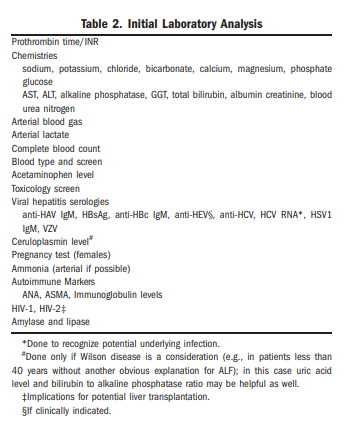

involved with patient transport may increase or even preclude transfer once stage III or IV encephalopathy develops.Initial laboratory examination must be extensive in order to evaluate both the etiology and severity of ALF (Table 2). Early testing should include routine chemistries (especially glucose, as hypoglycemia may be present and require correction), arterial blood gas measurements, complete blood counts, blood typing,

acetaminophen level and screens for other drugs and toxins, viral serologies (Table 2), tests for Wilson disease, autoantibodies, and a pregnancy test in females. Plasma ammonia, preferably arterial, may also be helpful.11,12 Liver biopsy, most often done via the transjugular route because of coagulopathy, is indicated when certain conditions such as autoimmune hepatitis, metastatic liver disease, lymphoma, or herpes simplex hepatitis are suspected, but is not required to determine prognosis. Imaging may disclose cancer or Budd

Chiari syndrome but is seldom definitive. The presence of a nodular contour can be seen in ALF and should not be interpreted as indicating cirrhosis in this setting.Once at the transplant facility, the patient’s suitability for transplantation should be assessed.13 Evaluation for transplantation should begin as early as possible, even before the onset of encephalopathy if possible. Social and financial considerations are unavoidably tied to the overall clinical assessment where transplantation is contemplated. It is also important to inform the patient’s family or other next of kin of the potentially poor prognosis and to include them in the decision-making process.

Resources:

(1) POSITION PAPER AASLD Position Paper: The Management of Acute Liver Failure: Update 2011 [Full Text Enhanced PDF] from The American Association For The Study Of Liver Diseases [AASLD].

(2) Introduction to the Revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Position Paper on Acute Liver Failure 2011 AND Corrections to the AASLD Position Paper: The Management of Acute Liver Failure: Update 2011 AND AASLD Position Paper: The Management of Acute Liver Failure: Update 2011 [The PDF of all three of the papers].

The PDF of Resource (2), although identical to Resource (1)’s enhanced PDF, is easier to quickly review.

(3) American Association For the Study of Liver Disease Practice Guidelines List