What follows is the Abstract from Resource (1) below, Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Gut. 2011 Oct;60(10):1309-16. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.228874. Epub 2011 May 11.

* Resource (1) below could better be titled “Guidelines for the appropriate GI Evaluation of Iron Deficiency Anemia” and is a great article.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

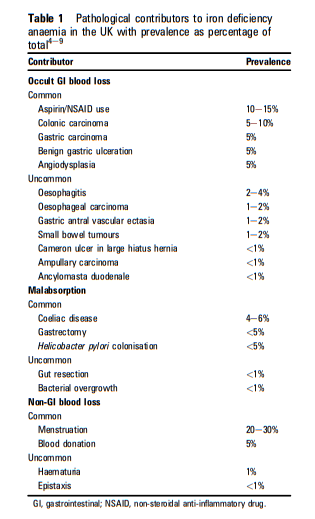

Iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) occurs in 2-5% of adult men and postmenopausal women in the developed world and is a common cause of referral to gastroenterologists. Gastrointestinal (GI) blood loss from colonic cancer or gastric cancer, and malabsorption in coeliac disease are the most important causes that need to be sought. DEFINING IRON DEFICIENCY ANAEMIA: The lower limit of the normal range for the laboratory performing the test should be used to define anaemia (B). Any level of anaemia should be investigated in the presence of iron deficiency (B). The lower the haemoglobin the more likely there is to be serious underlying pathology and the more urgent is the need for investigation (B). Red cell indices provide a sensitive indication of iron deficiency in the absence of chronic disease or haemoglobinopathy (A). Haemoglobin electrophoresis is recommended when microcytosis and hypochromia are present in patients of appropriate ethnic background to prevent unnecessary GI investigation (C). Serum ferritin is the most powerful test for iron deficiency (A).

INVESTIGATIONS:

Upper and lower GI investigations should be considered in all postmenopausal female and all male patients where IDA has been confirmed unless there is a history of significant overt non-GI blood loss (A). All patients should be screened for coeliac disease (B). If oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) is performed as the initial GI investigation, only the presence of advanced gastric cancer or coeliac disease should deter lower GI investigation (B). In patients aged >50 or with marked anaemia or a significant family history of colorectal carcinoma, lower GI investigation should still be considered even if coeliac disease is found (B). Colonoscopy has advantages over CT colography for investigation of the lower GI tract in IDA, but either is acceptable (B). Either is preferable to barium enema, which is useful if they are not available. Further direct visualisation of the small bowel is not necessary unless there are symptoms suggestive of small bowel disease, or if the haemoglobin cannot be restored or maintained with iron therapy (B). In patients with recurrent IDA and normal OGD and colonoscopy results, Helicobacter pylori should be eradicated if present. (C). Faecal occult blood testing is of no benefit in the investigation of IDA (B). All premenopausal women with IDA should be screened for coeliac disease, but other upper and lower GI investigation should be reserved for those aged 50 years or older, those with symptoms suggesting gastrointestinal disease, and those with a strong family history of colorectal cancer (B). Upper and lower GI investigation of IDA in post-gastrectomy patients is recommended in those over 50 years of age (B). In patients with iron deficiency without anaemia, endoscopic investigation rarely detects malignancy. Such investigation should be considered in patients aged >50 after discussing the risk and potential benefit with them (C). Only postmenopausal women and men aged >50 years should have GI investigation of iron deficiency without anaemia (C). Rectal examination is seldom contributory, and, in the absence of symptoms such as rectal bleeding and tenesmus, may be postponed until colonoscopy. Urine testing for blood is important in the examination of patients with IDA (B).

MANAGEMENT:

All patients should have iron supplementation both to correct anaemia and replenish body stores (B). Parenteral iron can be used when oral preparations are not tolerated (C). Blood transfusions should be reserved for patients with or at risk of cardiovascular instability due to the degree of their anaemia (C).

What follows are excerpts from the Guidelines, Resource (1) below:

Scope

These guidelines are primarily intended for Western

gastroenterologists and gastrointestinal (GI)

surgeons, but are applicable for other doctors seeing

patients with iron deficiency anaemia (IDA). They

are not designed to cover patients with overt blood

loss or those who present with GI symptoms. GI

symptoms or patients at particular risk of GI

disease should be investigated on their own merits.Anaemia

The World Health Organization defines anaemia as a haemoglobin (Hb) concentration below 13 g/dl in men over 15 years of age, below 12 g/dl in non-pregnant women over 15 years of age, and below 11 g/dl in pregnant women.1 The diagnostic criteria for anaemia in IDA vary between published studies.4e9 The normal range for Hb also varies between different populations in the UK. Therefore it is reasonable to use the lower limit of the normal range for the laboratory performing the test to define anaemia (B).

There is little consensus as to the level of anaemia that

requires investigation. The NHS National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence referral guidelines for suspected lower GI cancer suggest that only patients with Hb concentration <11 g/dlin men or <10 g/dl in non-menstruating women be referred.12 It has been suggested that these cut-off values miss patients with colorectal cancer, especially men.13 It is therefore recommended that any level of anaemia should be investigated in the presence of iron deficiency. Furthermore, it is recommended 13 that men with Hb concentration <12 g/dl and postmenopausal women with Hb concentration <10 g/dl should be investigated more urgently, since lower levels of Hb suggest more serious disease (A).Iron Deficiency

Modern automated cell counters provide measurements of the

changes in red cells that accompany iron deficiency: reduced meancell Hb (MCH)dhypochromiadand increased percentage of

hypochromic red cells and reduced mean cell volume (MCV)d

microcytosis.14 The MCH is probably the more reliable because it is less influenced by the counting machine used and by storage. Both microcytosis and hypochromia are sensitive indicators of iron deficiency in the absence of chronic disease or coexistent vitamin B12 or folate deficiency.15 An increased red cell distribution width will often indicate coexistent vitamin B12 or folat deficiency. Microcytosis and hypochromia are also present in many haemoglobinopathies (such as thalassaemia, when the MCV is often out of proportion to the level of anaemia compared with iron deficiency), in sideroblastic anaemia and in some cases of anaemia of chronic disease. Hb electrophoresis is recommended when microcytosis is present in patients of appropriate ethnic background to prevent unnecessary GI investigation (C).The serum markers of iron deficiency include low ferritin, low

transferrin saturation, low iron, raised total iron-binding

capacity, raised red cell zinc protoporphyrin, and increased

serum transferrin receptor (sTfR). Serum ferritin is the most

powerful test for iron deficiency in the absence of inflammation

(A). The cut-off concentration of ferritin that is diagnostic varies

between 12 and 15 mg/l.16 17 This only holds for patients

without coexistent inflammatory disease. Where there is

inflammatory disease, a concentration of 50 mg/l or even more

may still be consistent with iron deficiency.1 The sTfR concentration is said to be a good marker of iron deficiency in healthy subjects,18 but its utility in the clinical setting remains to be proven [as of 2011 when these guidelines were written]. Several studies have shown that the sTfR/log10 serum ferritin ratio provides superior discrimination to either test on its own, particularly in chronic disease.19Functional Iron Deficiency*

‘Functional iron deficiency’* occurs where there is an inadequate

iron supply to the bone marrow in the presence of storage iron

in cells of the monocyte-macrophage system. Perhaps the most

important clinical setting for this is in patients with renal failure

who require parenteral iron therapy to respond to administered

erythropoietin to correct anaemia. Functional iron deficiency

also occurs in many chronic inflammatory diseases (eg, rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease)-the anaemia of chronic disease.

*’Functional Iron Deficiency’ is also called Iron Restricted Erythropoesis and is well discussed in Resource (2) below: Detection, evaluation, and management of iron-restricted erythropoiesis [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Blood. 2010 Dec 2;116(23):4754-61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-286260. Epub 2010 Sep 8.

Investigations

History

Borderline iron-deficient diets are common, and a dietary history should be taken to identify poor iron intake. The use of aspirin and non-aspirin NSAIDs should be noted, and these drugs stopped where the clinical indication is weak or other choices are available. Family history of IDA (which may indicate inherited disorders of iron absorption 23), haematological disorders (eg, thalassaemia), telangiectasia and bleeding disorders should be sought. A history of blood donation or any other source of blood loss should be obtained. The presence of one or more of these factors in the history should not, however, usually deter further investigation.

A significant family history of colorectal carcinoma should be sought-that is, one affected first-degree relative <50 years old or two affected first-degree relatives. A previous history of IDA may alter the order or appropriateness of tests, especially if longstanding.

Upper And Lower GI Evaluations

Upper and lower GI investigations should be considered in all

postmenopausal female and all male patients where IDA has

been confirmed unless there is a history of significant overt non-GI blood loss. In the absence of suggestive symptoms (which are

unreliable), the order of investigations is determined by local

availability, although all patients should be screened for coeliac

disease with serology (B)-see below. If oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) is performed as the initial GI investigation, only the presence of gastric cancer or coeliac disease, as explained below, should deter lower GI investigation (B). In particular, the presence of oesophagitis, erosions and peptic ulcer disease should not be accepted as the cause of IDA until lower GI investigations have been carried out. Small-bowel biopsy samples should be taken at OGD if coeliac serology was positive or not performed. Colonoscopy has the following advantages over radiology: it allows biopsy of lesions, treatment of adenomas, and identification of superficial pathology such as angiodysplasia and NSAID damage. Performing gastroscopy and colonoscopy at the same session speeds investigation and saves time for both the hospital and the patient, because only one attendance for endoscopy is required. Radiographic imaging is a sufficient alternative where colonoscopy is contraindicated. The sensitivity of CT colography for lesions >10 mm in size is over 90%.25 Barium enema is less reliable, but is still useful26 if colonoscopy or CT colography are not readily available.Screening for and further investigation of coeliac disease

Ideally coeliac serology-tissue transglutaminase (tTG)

antibody 27 or endomysial antibody if tTG antibody testing is not available-should be undertaken at presentation, but if this has not been carried out or if the result is not available, duodenal biopsy specimens should be taken. If coeliac serology is negative, small-bowel biopsies need not be performed at OGD unless there are other features, such as diarrhoea, which make coeliac disease more likely (B). The pretest probability of coeliac disease in those with IDA alone is w5%. The negative likelihood ratio for the tTG antibody test using human recombinant tTG is 0.06.27 Thus, if the tTG antibody test is negative, the post-test probability of coeliac disease is 0.3%, which is less than in the general population. This means that duodenal biopsy samples will need to be taken from w330 tTG antibody-negative patients to detect one extra patient with coeliac disease at an estimated additional cost of £35 000. If coeliac serology is positive, coeliac disease is likely and should be confirmed by small-bowel biopsy. Although concurrent testing for IgA deficiency, which is found in 2% of patients with coeliac disease, has been recommended, we do not consider it necessary to test for it routinely, because it only results in the post-test probability of coeliac disease with a negative tTG antibody test changing slightly from 0.3% to 0.2%, which is notclinically significant. However, it is advised28 if low absorbance readings are shown in the IgA tTG antibody assay.Further GI investigations are not usually necessary if coeliac

disease is diagnosed. However, the lifetime risk of GI malignancy in patients with coeliac disease is slightly increased, 29 particularly within 1 year of diagnosis, so investigation with colonoscopy should be considered if additional risk is present-for example, if age is >50 years or if there is a significant family

history of colorectal carcinoma. If IDA develops in a patient

with treated coeliac disease, upper and lower GI investigation is

recommended in those aged >50 in the absence of another

obvious cause. In the rare case of normal small-bowel histology

with positive serology, we recommend that investigation should

proceed as if coeliac serology was negative.Further Evaluation

Further imaging of the small bowel is probably not necessary

unless there is an inadequate response to iron therapy, especially if transfusion dependent (B).3 7 Follow-up studies have shown this approach to be reasonably safe26 30 31 provided that dietary deficiency is corrected, NSAIDs have been stopped, and the Hb concentration is monitored.Helicobacter pylori colonisation may impair iron uptake and

increase iron loss, potentially leading to iron deficiency and

IDA.36e39 Eradication of H pylori appears to reverse anaemia in anecdotal reports and small studies.40 H pylori should be sought by non-invasive testing*, if IDA persists or recurs after a normal OGD and colonoscopy, and eradicated if present (C). H pylori urease (CLO) testing of biopsy specimens taken at the initial gastroscopy is an alternative approach.

*For an article on non-invasive testing of H pylori, see 2018 Resource (4) below, Non-invasive diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori infection.

Giardia lamblia has occasionally been found during the

investigation of IDA. If there is associated diarrhoea, then small bowel biopsy samples will be taken anyway and may detect

this. Where giardiasis is suspected, stool should be sent for

ELISA, even if histology of duodenal biopsy samples is negative.Radiological imaging of the mesenteric vessels is of limited use

but may be of value in transfusion-dependent IDA for demonstrating vascular malformations or other occult lesions.

Similarly, diagnostic laparotomy with on-table enteroscopy is

rarely required in cases that have defied diagnosis by other

investigations. There is no evidence to recommend labelled red

cell imaging or Meckel’s scans in patients with IDA.Iron Therapy

Treatment of an underlying cause should prevent further iron

loss, but all patients should have iron supplementation both to

correct anaemia and replenish body stores (B).Follow-up

Once normal, the Hb concentration and red cell indices should

be monitored at intervals. We suggest 3 monthly for 1 year, then

after a further year, and again if symptoms of anaemia develop

after that. Further oral iron should be given if the Hb or red cell

indices fall below normal (ferritin concentrations can be reserved for cases where there is doubt). Further investigation is only necessary if the Hb and red cell indices cannot be maintained in this way. It is reassuring that iron deficiency does not recur in most patients in whom a cause is not found after upper GI endoscopy, testing for coeliac disease, and large-bowel investigation.26 31Special Considerations

Investigation of Premenopausal Women

IDA occurs in 5-12% of otherwise healthy premenopausal

women55 56 and is usually due to menstrual loss, increased demands in pregnancy and breast feeding, or dietary deficiency.57Coeliac disease is present in up to 4% of premenopausal women in these studies. All premenopausal women with IDA should be screened for coeliac disease (B).

Age is the strongest predictor of pathology in patients with IDA,9 and thus GI investigation as outlined above is recommended for asymptomatic premenopausal women with IDA aged 50 years or older (B).

OGD should be considered for any premenopausal women

with IDA and upper GI symptoms according to the Department

of Health referral guidelines for suspected upper GI cancer.12Colonic investigation in premenopausal women aged <50 years should be reserved for those with colonic symptoms, a strong family history (two affected first-degree relatives or just one first-degree relative affected before the age of 50 years 67), or

persistent IDA after iron supplementation and correction of

potential causes of losses (eg, menorrhagia, blood donation and

poor diet).Patients with significant comorbidity

The appropriateness of investigating patients with frailty and/or severe comorbidity needs to be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Young Men

Although the incidence of important GI pathology in young

men is low, there are no data on the yield of investigation in those with IDA. In the absence of such data, we recommend

that young men should be investigated in the same manner as

older men (C). Where there is an obvious cause of blood loss (eg,

blood donation), it is reasonable to avoid investigations unless

anaemia recurs despite correction of the cause of blood loss.Pregnant Women

Mild IDA is common in pregnancy, and iron replacement should

be encouraged as soon as the diagnosis is made. A careful history and examination should be made, specifically seeking a family history of gastrointestinal neoplasia or coeliac disease. Coeliac serology should be carried out. If it is positive, endoscopy and duodenal biopsy can be performed, as there is no evidence this is unsafe in pregnancy. If there is concern about lower GI pathology, further investigation should be considered, although in some patients this may be delayed until after delivery. Performing unsedated flexible sigmoidoscopy in pregnancy is considered quite safe.68 However, there are insufficient data on the safety of performing colonoscopy in pregnancy, and, because of its potential to cause serious adverse events, it should be reserved for very strong indications.68 MR colography is believed to be safe for mother and fetus and should be preferred to radiological imaging. The National Radiological Protection Board considers it prudent to avoid MRI in the first trimester.Post-Gastrectomy

IDA is very common in patients with partial or total gastrectomy,69 probably because of poor chelation and absorption of iron as a result of loss of ascorbic acid and hydrochloric acid, and loss of free iron in exfoliated cells. However, these patients also have a two- to three-fold increased risk of gastric cancer after 20 years, and probably an increased risk of colon cancer. Investigation of IDA in post-gastrectomy patients aged >50 years of age is therefore recommended (C). Bariatric surgery can lead to iron deficiency, but iron supplementation is usually recommended after surgery to prevent the problem.

Use of Warfarin And Aspirin

No significant difference in the prevalence of GI cancer was

found in patients taking aspirin or warfarin, either alone or in

combination, compared with patients not taking these drugs.9

IDA should therefore not be attributed to these drugs until GI

investigations have been completed.Use of Proton Pump Inhibitor

There are no data to indicate that proton pump inhibitors cause

IDA in humans. Patients taking these drugs should not be

considered less likely to have malignancyIron Deficiency Without Anemia

Iron deficiency without anaemia (confirmed by low serum

ferritin-hypoferritinaemia) is three times as common as IDA,63

but there is no consensus on whether these patients should be

investigated, and further research is needed. The largest study

shows very low prevalence of GI malignancy in patients with

iron deficiency alone (0.9% of postmenopausal women and men,

and 0% of premenopausal women).63 Higher rates have been

reported only in more selected groups.70 71 In the absence of firm

evidence, we tentatively recommend coeliac serology in all these

patients but that other investigation be reserved for those with

higher-risk profiles (eg, age >50 years) after discussion of the

risks and potential benefits of upper and lower GI investigation

(C). All others should be treated empirically with oral iron

replacement for 3 months and investigated if iron deficiency

recurs within the next 12 months (C).

Resources:

(1) Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Gut. 2011 Oct;60(10):1309-16. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.228874. Epub 2011 May 11.

* Resource (1) above could better be titled “Guidelines for the appropriate GI Evaluation of Iron Deficiency Anemia” and is a great article.

(2) Detection, evaluation, and management of iron-restricted erythropoiesis [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Blood. 2010 Dec 2;116(23):4754-61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-286260. Epub 2010 Sep 8.

The above article has been cited 67 times in PubMed.

(3) Case Report:Iron deficiency without anemia – a clinical challenge [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Clin Case Rep. 2018 Apr 17;6(6):1082-1086. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.1529. eCollection 2018 Jun.

(4) Non-invasive diagnostic tests for Helicobacter pylori infection [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Mar 15;3:CD012080. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012080.pub2.