In this post I link to and excerpt from the chapter Hypomagnesemia, November 2, 2018, of Dr. Farkas’ incredible Internet Book Of Critical Care [Link is to TOC]. And after reviewing the chapter, listen to the 25 minute summary podcast of the chapter. The first part of the podcast discusses hypomagnesemia. And hypermagnesemia is reviewed during the last 8 minutes of the podcast.

Dr. Farkas has created this Table of Contents of the chapter and each heading is a direct link to that part of the chapter:

CONTENTS

All that follows are excerpts from the Hypomagnesemia Chapter of The Internet Book Of Critical Care [except where noted.- material in brackets]:

diagnosis

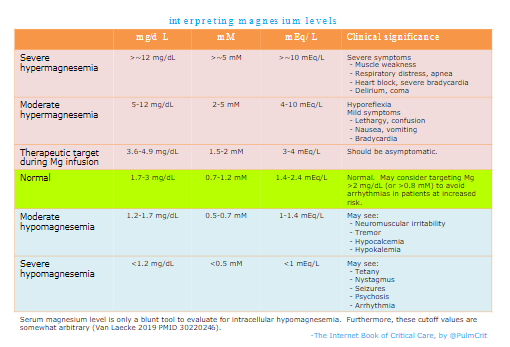

magnesium level

physical examination

- Hyperreflexia

EKG manifestations

- Most common is prolonged QT interval, which may progress to Torsade de Pointes.*

- May prolong all intervals (PR, QRS, QT).

- May increase risk of various other arrhythmias (especially atrial fibrillation).

[*Torsade de Pointes – Help From Dr Josh Farkas Of The Internet Book Of Critical Care and PulmCrit With Additional Resources. Posted on April 30, 2019 by Tom Wade MD]

cardiac

- Cardiac arrest from Torsade de pointes.

- Atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter

- Frequent premature atrial complexes or premature ventricular complexes

neuromuscular hyperexcitability

- seizure

- delirium, depression, psychosis

- cerebellar dysfunction (ataxia, downbeat nystagmus*, slurred speech, tremor)

- paresthesias

- muscle cramps, tremors, fasciculation, hyperreflexia, even tetany

[*What are the causes of downbeat nystagmus?

Updated: Oct 17, 2018. Author: Christopher M Bardorf, MD, MS from Medscape.com]

Downbeat nystagmus may be caused by hypomagnesemia, Wernicke’s encephalopathy, or structural brain lesions. Get a CT scan, but also check electrolytes & consider thiamine.

other potential consequences

- Insulin resistance

causes

medications

- Diuretics (except for potassium-sparing diuretics)

- Antibiotics

- Aminoglycosides

- Amphotericin B

- Pentamidine

- Foscarnet

- Cyclosporine & tacrolimus

- Platinum-based chemotherapy

- EGFR receptor blockers (cetuximab, panitumumab, matuzumab)

- Proton pump inhibitors

other electrolyte abnormalities (electrolytic disarray)

- Hypercalcemia

- Hyperphosphatemia

- Metabolic acidosis

renal disease

- Chronic tubulointerstitial disease

- Diuresis after recovery from ATN or renal obstruction

- Administration of Mg-free IV fluid

- Osmotic diuresis (e.g. hyperglycemia)

- Renal tubular acidosis

gastrointestinal disease

- Malabsorption

- Proton pump inhibitors

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Diarrhea, vomiting, NG suction

- Pancreatitis

- Diarrhea

specific situations

- Chronic alcoholism, protein calorie malnutrition, anorexia

- Diabetes, insulin, refeeding syndrome

- Large volume transfusion of citrated blood products

- Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT)

- Ethylene glycol intoxication

- Sepsis

evaluation of cause

investigation

- Check complete panel of electrolytes (including Ca/Mg/Phos).

treatment

treat co-existing electrolyte abnormalities

- Treat hypokalemia

- Hypomagnesemia causes hypokalemia.

- It is often the combination of these two abnormalities that causes arrhythmia. Thus, prompt treatment of both abnormalities may rapidly reduce the risk of arrhythmia rapidly.

- Treat hypocalcemia

- Magnesium sulfate may complex with calcium, decreasing the calcium level further.

- Treat hypercalcemia or hyperphosphatemia (which may cause hypomagnesemia)

general principles of magnesium treatment

- Magnesium is generally extremely safe, with the following exceptions:

- Patients with myasthenia gravis may be at increased risk of muscle weakness.

- Renal failure (e.g. GFR < 30 ml/min) may cause magnesium accumulation. These patients may be treated with a normal “loading” dose of magnesium up-front, but care is needed with repeated dosing.

- Magnesium repletion can be difficult:

- Oral magnesium is poorly absorbed and causes diarrhea.

- IV magnesium boluses will cause transient elevation in the serum magnesium level, causing magnesium secretion by the kidneys. Most of the administered magnesium may be excreted in the urine.

- Most of the body’s magnesium is intracellular. The goal is really to get magnesium into the cells, but cellular uptake occurs slowly.

(1) mild hypomagnesemia (e.g. ~1.5-2 mg/dL or ~0.6-0.8 mM)

- Oral magnesium may be used if:

- i) Patient is taking oral medications

- ii) There is no interaction with other medications (e.g. tetracyclines and calcium channel blockers)

- Dosing of oral magnesium:

- Magnesium oxide, 400 mg PO BID

- Or milk of magnesia (magnesium hydroxide), 15 ml daily

- If unable to give oral magnesium, may give 2 grams IV magnesium sulfate.

(2) moderate hypomagnesemia (e.g. ~1.2-1.5 mg/dL or ~0.5-0.6 mM)

- Intermittent administration of 2-4 grams magnesium sulfate IV.

- Higher doses may be preferred if renal function is normal and hypomagnesemia is more severe.

- Infusing the dose over a longer time period may improve intracellular absorption and could also be safer.

(3) severe asymptomatic hypomagnesemia (e.g. <1.2 mg/dL or <0.5 mM)

- Severe hypomagnesemia generally reflects a low total body magnesium content.

- There are roughly two ways to do this (depending largely on logistics)

- (i) Multiple scheduled doses of IV magnesium (e.g. 2 grams IV magnesium sulfate q6hr-q8hr).

- (ii) Continuous infusion of IV magnesium (e.g. 4-8 grams of IV magnesium sulfate over 24 hours)

- Follow extended electrolyte panel (electrolytes plus Ca/Mg/Phos) daily. Draw labs several hours after completion of the infusion, to allow for distribution of the magnesium.

- For patients with normal renal function, electrolytes may be followed ~daily.

- For patients with renal insufficiency, electrolytes should be followed more carefully (greater risk of hypermagnesemia).

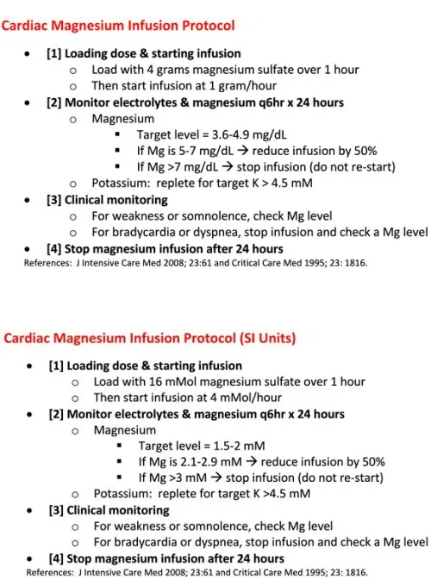

(4) management of life-threatening hypomagnesemia (e.g. Torsade de Pointes, seizures)

- Initial loading dose of four grams*

- 2 grams IV magnesium sulfate over 5-15 minutes.

- 2 additional grams IV over 30-60 min.

*This table is copied from 2015 Handbook of Emergency Cardiovascular Care for Healthcare Providers, p 55:

| Drug/Therapy | Indications/Precautions | Adult Dosages |

| Magnesium Sulfate | Indications

-Recommened for use in cardiac arrest only if torsades de pointes or suspected hypomagnesium. -Life-threatening ventricular arrythmias due to digitalis toxicity. -Routine administration in hospitalized patients with AMI is not recommended. |

Cardiac Arrest (Due to Hypomagnesemia or Torsades de Pointes)

1 to 2 g (2 to 4 ml of a 50% solution diluted in 10 ml [eg, D5W, normal saline] given IV/IO).

|

| Precautions

-Occasional fall in blood pressure with rapid administration. -Use with caution if renal failure present. |

Torsades de Pointes with a Pulse or AMI with Hypomagnesium

-Loading dose of 1 to 2 g maixed in 50 to 100 ml of diluent (eg, D5W, normal saline) over 5 to 60 minutes IV. -Follow with 0.5 to 1 g per hour IV (titrate to control torsades |

- Maintenance dose

-

- GFR > 30 ml/min: magnesium infusion using the protocol shown below. This protocol was initially designed for use in atrial fibrillation, but it is safe and can be used in a variety of situations where aggressive magnesium loading is desired. When the magnesium infusion protocol is being used, this should be pasted into the chart (electronically or physically) so that everyone is on the same page.

- GFR < 30 ml/min: follow magnesium levels and re-dose based on level.

- Potential complications from intravenous magnesium:

- Hypermagnesemia may occur, resulting in AV block or muscular weakness.

- Magnesium sulfate can reduce calcium levels. This is generally minor, but may exacerbate pre-existing hypocalcemia.

balanced nephron diuretic strategy?

- For patients requiring large volume diuresis, loop diuretics may cause magnesium wasting.

- Potassium-sparing diuretics (e.g. amiloride or trimaterene) may have a magnesium-sparing effect.

- A combination diuretic regimen (e.g. loop diuretic, thiazide diuretic, and potassium-sparing diuretic) may cause the fewest electrolytic derangements.

Pitfalls

- Patients with severe hypomagnesemia often have a total-body magnesium deficiency. Don’t just give 2-4 grams magnesium and expect this to fix the problem. Most of the magnesium administered isn’t absorbed by the cells, so severe hypomagnesemia often requires a magnesium infusion or repeated doses.

- Make sure to check magnesium levels on patients with atrial fibrillation (especially difficult-to-treat atrial fibrillation). If myocardial irritability is being driven by hypomagnesemia, repletion of magnesium may help substantially.

- About half of patients with hypokalemia are also hypomagnesemic (29610664). Consider empiric administration of magnesium along with potassium to treat hypokalemia.

Going further

- Additional information on dosing magnesium: see this guideline from GlobalRPH.com.

- Hypomagnesemia (CoreEM, Brian Gilberti)

- Hypomagnesemia (WikEM)