In addition to the article and resources referenced in this post, please see:

- Links To And Excerpts From “How to Diagnose and Manage Angina Without Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: Lessons from the British Heart Foundation CorMicA Trial”

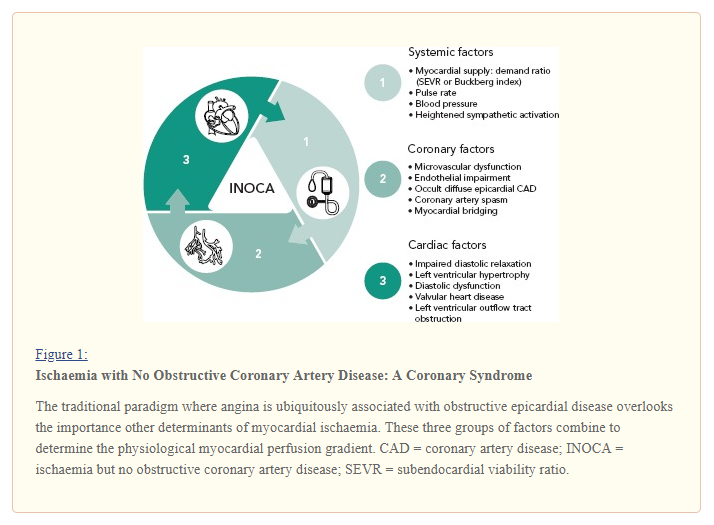

Posted on June 18, 2019 by Tom Wade MD- Here is an excellent summary graph from the article:

- Links To And Excerpts From “ESC working group position paper on myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries”

Posted on June 18, 2019 by Tom Wade MD - Links To And Excerpts From “Coronary Microvascular Function and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Women With Angina Pectoris and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: The iPOWER Study”

Posted on June 18, 2019 by Tom Wade MD

This post contains links to and excerpts from Contemporary Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Myocardial Infarction in the Absence of Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Circulation. 2019 Apr 30;139(18):e891-e908.

Here are excerpts:

Epidemiology

Clinical studies have reported a prevalence of MINOCA

of 5% to 6% of AMI cases,6 with a range between 5%

and 15% depending on the population examined.5,6,14–16

Although MINOCA can present with or without STsegment elevation on the ECG, patients with MINOCA are less likely to have electrocardiographic ST-segment deviations and have smaller degrees of troponin elevation than their AMI counterparts with obstructive CAD (AMI-CAD).14,16Definitions

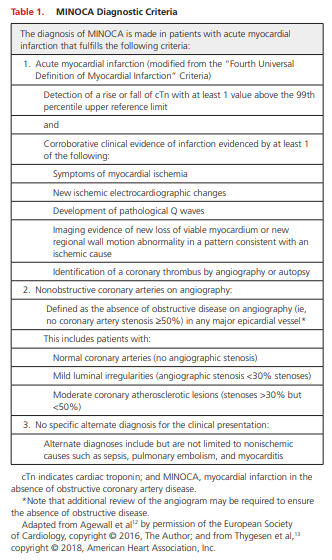

With this revised concept of AMI [from the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018) – Resource (1) below], the term MINOCA should be reserved for patients in whom there is an ischemic basis for their clinical presentation. Thus, in the evaluation of patients with a suspected AMI (based on cardiac biomarkers and corroborative clinical evidence),

despite the absence of obstructive CAD, it is imperative

to exclude (1) clinically overt causes for the elevated troponin (eg, sepsis, pulmonary embolism), (2) clinically overlooked obstructive disease (eg, complete occlusion of a small coronary artery subsegment resulting from plaque disruption or embolism, or an overlooked ≥50% distal

stenosis of a coronary artery), and (3) clinically subtle nonischemic mechanisms of myocyte injury that can mimic

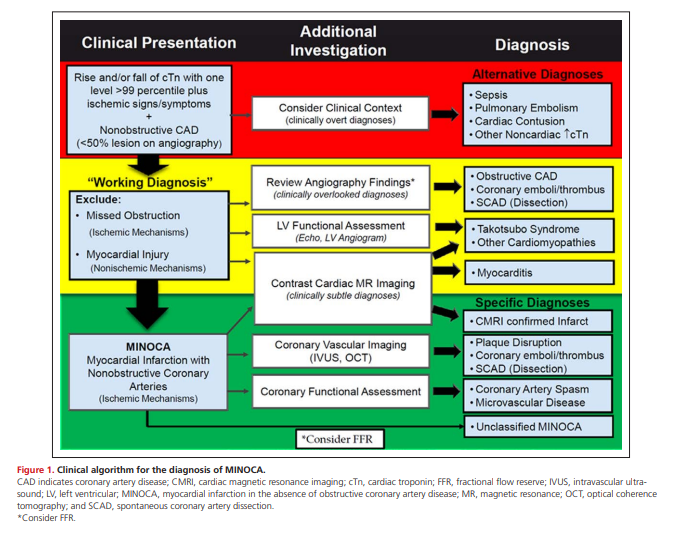

myocardial infarction (eg, myocarditis) (Figure 1). Once

these have been considered and excluded by use of available diagnostic resources, a diagnosis of MINOCA can be

made (Table 1). This diagnosis is inherently descriptive and

should prompt physicians to seek an underlying diagnosis.Although an obstructive lesion is strictly a pathophysiological

concept that requires physiological evaluation, functional assessment is not routinely undertaken in all patients undergoing coronary angiography, and clinical decisions are often made on the basis of visual angiographic estimation of lesion diameter stenosis. Yet it is important to realize that this approach to classification of lesion severity is extremely subjective, with substantial interobserver variability.21 [Resource (3) below] Furthermore, the angiographic severity of a lesion is not static and can vary between angiograms as a result of changes in vasomotor tone or dissolution of coronary

thrombi.22 [Resource (4) below] In accordance with this pragmatic angiographic approach, it is useful to categorize MINOCA patients into those with angiographically normal coronary arteries (ie, no angiographic disease) and minimal lumen irregularities (angiographic disease <30% stenosis) and those with angiographically mild to moderate coronary atherosclerosis (≥30% but <50%). . . . Although there are limited data evaluating the role of fractional flow reserve (FFR)

testing in MINOCA patients with moderate stenoses,

FFR may be considered in select patients with borderline “obstructive” disease based on extrapolation from data in stable patients that showed that up to one-quarter of patients with 30% to 50% stenosis have functionally significant stenoses when measured using FFR.24 If FFR is used, we propose that

only patients with FFR findings >0.80 be included as a working diagnosis of MINOCA.The Traffic Light Sequence:

The “Traffic Light” Sequence for the Diagnosis of MINOCA

Figure 1 provides a clinical algorithm for the diagnosis

of MINOCA. The initial evaluation in patients with suspected AMI and nonobstructive CAD involves careful consideration of the clinical context and the exclusion of clinically overt causes for a myocardial injury that led physicians to an initial diagnosis of AMI but on further review was not likely a result of an ischemic event (red section of Figure 1). If AMI remains the clinical diagnosis of choice after this step, the clinician should exclude potentially overlooked obstructive CAD by re-reviewing

the angiogram and consider further investigation to exclude clinically subtle nonischemic mechanisms of myocardial injury (yellow section of Figure 1). Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) is recommended as a key investigation in MINOCA because it can exclude myocarditis, takotsubo syndrome, and cardiomyopathies, as well as provide imaging confirmation of AMI. However, CMRI is not widely available, and it is therefore not pragmatic to recommend it as an essential step for the diagnosis of MINOCA. After excluding alternate diagnoses, the clinician arrives in the green section of Figure 1, where a diagnosis of MINOCA or CMRI-confirmed MINOCA can be made. In specialized centers, the clinician may consider additional studies to elucidate the underlying cause(s) of MINOCA. It is important to recognize that the order of the diagnostic evaluations advised might not always follow the algorithm provided. For example, CMRI might be performed

after intracoronary imaging.Several aspects of this working-diagnosis pathway

are noteworthy:• Clinically overt presentation: The initial presentation might provide an obvious clinical context for

the diagnosis (eg, myocardial injury associated

with septic shock) that would not be considered

MINOCA, so that no further diagnostic evaluation

is required.

• Access to cardiac investigations: Some cardiac

investigations (eg, CMRI) might not be readily

available in some centers, so that the diagnosis of

MINOCA may need to be made on clinical grounds

alone. However, consideration should be given to

these alternate diagnoses even in the absence

of advanced imaging. Notably, although the use

of CMRI is strongly encouraged, the absence of

myocardial necrosis on CMRI does not necessarily exclude MINOCA as a diagnosis, because a lack of myocardial necrosis on CMRI has been reported in patients with other findings that support MINOCA.25

• Dynamic diagnosis: With further evaluation, the

differential clinical diagnoses may change. For example, an initial diagnosis suggestive of takotsubo syndrome based on left ventricular imaging studies may later change to MINOCA if CMRI demonstrates myocardial necrosis. Similarly, an initial diagnosis of MINOCA may later change to myocarditis on the basis of CMRI findings.

• Takotsubo syndrome: The mechanism (ischemic versus nonischemic) responsible for this intriguing disorder remains uncertain. Criteria for takotsubo syndrome require the wall motion abnormalities to be transient, and therefore, early in the course, the working diagnosis might be MINOCA. The “Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction” does not consider takotsubo syndrome a myocardial infarction,13 and therefore, we have categorized takotsubo syndrome separately for uniformity. Although takotsubo syndrome can clinically mimic MINOCA, it appears to be a distinctly different

syndrome and therefore should be considered separately.

• Evaluating ischemic mechanisms: Invasive coronary imaging and functional testing can provide therapeutic direction for patients with MINOCA (eg, use of calcium channel blockers in coronary spasm) and should be used selectively after consideration of the benefits and risks.

• Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD):

The diagnosis of SCAD is usually made after careful

review of the angiogram. If obstructive disease is noted, this would eliminate a diagnosis of MINOCA. However, on occasion, SCAD is only recognized after intracoronary imaging is performed, and hence, imaging may be needed to firmly establish the diagnosis, especially in SCAD subtype II (diffuse long, smooth, tapering nonobstructive lesions).26

Additional Resources:

(1) Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018) [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Originally published13 Nov 2018. Circulation. 2018;138:e618–e651.

(2) What’s new in the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial infarction? [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. European Heart Journal, Volume 39, Issue 42, 07 November 2018, Pages 3757–3758. Here is an excerpt:

In addition to the clinical sections of the Consensus Document on

the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction, it also contains a considerable amount of detailed information regarding analytic issues of cTn, about the use of ECG, and the application of imaging for diagnosing myocardial injury and MI.

Resource (2) above is a great brief summary of Resource (1).

(3) Comparison of Clinical Interpretation With Visual Assessment and Quantitative Coronary Angiography in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Contemporary Practice: The Assessing Angiography (A2) Project [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Circulation. 2013 Apr 30;127(17):1793-800. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001952. Epub 2013 Mar 7.

The above article has been cited by 13 articles in PubMed Central.

(4) Exaggeration of nonculprit stenosis severity during acute myocardial infarction: implications for immediate multivessel revascularization [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002 Sep 4;40(5):911-6.

The above article has been cited by 17 articles in PubMed Central.

(5) International standardization of diagnostic criteria for microvascular angina [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Download Full Text PDF from Research Gate]. Int J Cardiol. 2018 Jan 1;250:16-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.08.068. Epub 2017 Sep 8.

The above article has been cited by 14 PubMed Central articles.

(6) Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging Tutorial from The Atlas Of Human Cardiac Anatomy from The University of Minnesotta 2019.