In this post I link to and excerpt from the following:

Evaluation of a programme for ‘Rapid Assessment of Febrile Travelers’ (RAFT): a clinic-based quality improvement initiative [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. BMJ Open. 2016 Jul 29;6(7):e010302. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010302.

Here are excerpts from the above:

ABSTRACT

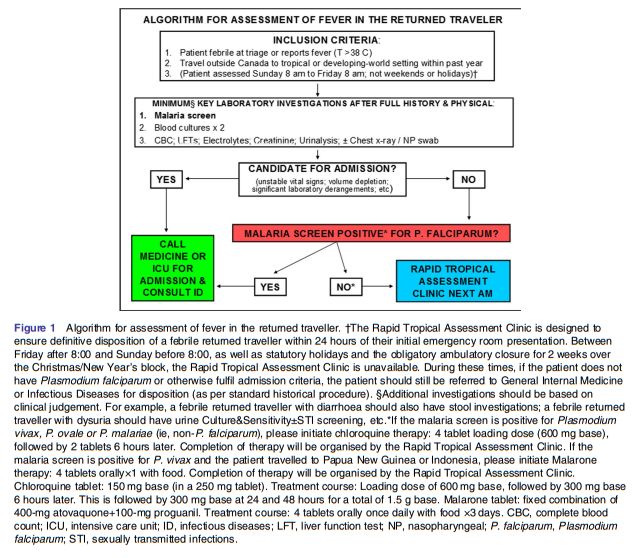

Background: Fever in the returned traveller is a potential medical emergency warranting prompt attention to exclude life-threatening illnesses. However, prolonged evaluation in the emergency department (ED) may not be required for all patients. As a quality improvement initiative, we implemented an algorithm for rapid assessment of febrile travelers (RAFT) in an ambulatory setting.

Methods: Criteria for RAFT referral include: presentation to the ED, reported fever and travel to the tropics or subtropics within the past year. Exclusion criteria include Plasmodium falciparum malaria, and fulfilment of admission criteria such as unstable vital signs or significant laboratory derangements. We

performed a time series analysis preimplementation and postimplementation, with primary outcome of wait time to tropical medicine consultation. Secondary outcomes included number of ED visits averted for repeat malaria testing, and algorithm adherence.Results: From February 2014 to December 2015, 154 patients were seen in the RAFT clinic: 68 men and 86 women. Median age was 36 years (range 16–78 years). Mean time to RAFT clinic assessment was 1.2 ±0.07 days (range 0–4 days) postimplementation, compared to 5.4±1.8 days (range 0–26 days) prior to implementation ( p<0.0001). The RAFT clinic averted 132 repeat malaria screens in the ED over the study

period (average 6 per month). Common diagnoses were: traveller’s diarrhoea (n=27, 17.5%), dengue (n=12, 8%), viral upper respiratory tract infection (n=11, 7%), chikungunya (n=10, 6.5%), laboratory-confirmed influenza (n=8, 5%) and lobar pneumonia (n=8, 5%).Conclusions: In addition to provision of more timely care to ambulatory febrile returned travellers, we reduced ED bed usage by providing an alternate setting for follow-up malaria screening, and treatment of infectious diseases manageable in an outpatient setting, but requiring specific therapy

See Malaria Diagnosis (United States) from The Centers For Disease And Prevention (CDC) for testing recomendation.

CONCLUSIONS

Through implementation of a RAFT programme, we

have been able to provide more timely care to ambulatory febrile returned travellers and, in doing so, fill a gap in care faced by such travellers prior to implementation of the programme. We have also reduced ED bed-usage by providing an alternate setting for follow-up malaria screening. In addition, we have offloaded the responsibility for treatment of infectious diseases that can be managed in an outpatient setting, but require specific therapy, such as acute urinary tract infections, from the ED. Our programme underscores the range of febrile illnesses that are imported to Canada by travellers on a daily basis, and reinforces the need to combine history, physical examination and a minimum set of laboratory investigations to exclude potentially life threatening imported illnesses such as malaria and bacteraemia.