In this post, I link to and excerpt from Dr. Josh Farkas‘ Internet Book Of Critical Care [Link is to the Table of Contents] chapter, Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH), June 8, 2021.

Note to myself: As always, I excerpt because doing so helps me remember the materials. The excerpts in this post are not even close to complete. So when reviewing this material go directly to Dr. Farkas’ chapter, Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH), June 8, 2021 and review the chapter there.

And below are a list of IBCC chapters that are directly related to subarachnoid hemorrhage and to neurocritical care.

- Anticoagulant reversal

- Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome (RCVS).

- Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome (PRES).

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI).

- Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT).

- Elevated intracranial pressure (ICP)

- Takotsubo syndrome

- Approach to new fever or rigors in the ICU patient

For an outstanding resource on Subarachnoid Hemorrage Imaging, see Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Dr Mostafa El-Feky and Assoc Prof Frank Gaillard et al. Radioaedia [accessed 7-6-2021].

Note that you can search Radiopaedia for articles [116] related to subarachnoid hemorrhage, cases [191], and other resources.

All that follows is from the above chapter.

CONTENTS

- Rapid Reference

- Epidemiology

- Presentation

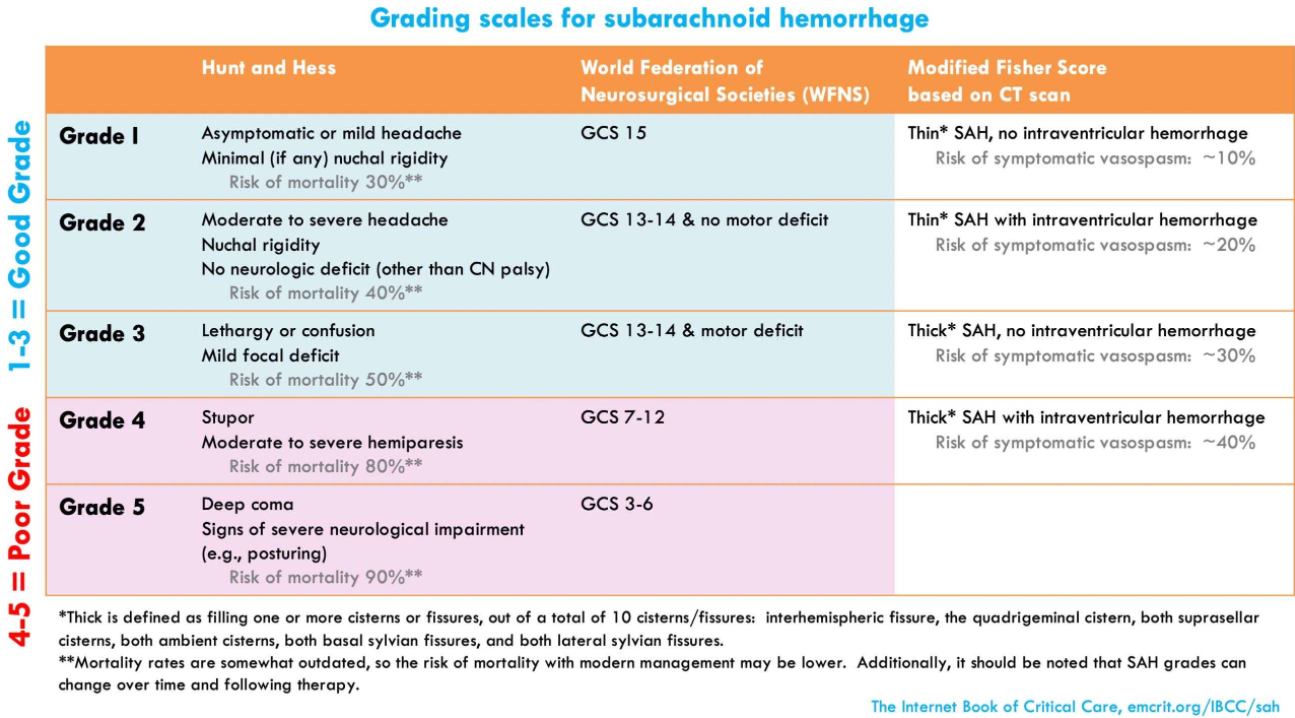

- Grading scales

- Diagnostic approach

- Management: Neurologic issues

- Management: Non-neurologic issues

- Podcast

- Questions & discussion

- Pitfalls

- PDF of this chapter (or create customized PDF)

rapid reference

SAH initial management:

rapid diagnostics

- Coagulation labs (INR, PTT, fibrinogen).

- Review of any anticoagulant medications the patient is taking.

- CT angiography (CTA).

consultation

- Neurointerventional radiology & neurosurgery.

- Consider: aneurysm protection, external ventricular drain.

coagulation management

- Aggressive management of any endogenous or exogenous coagulopathy.

- See chapter on anticoagulant reversal.

blood pressure control (more)

- Usually target MAP below ~110 mm (but may be personalized, based on baseline blood pressure).

- Treat pain immediately, before starting an antihypertensive.

- Often begin with an infusion (e.g., nicardipine or clevidipine).

- Once stable, add nimodipine if tolerated to prevent vasospasm (ideally 60 mg PO q4hr).

seizure prophylaxis & diagnosis (more)

- Prophylactic levetiracetam for all patients.

- Consider vEEG for comatose patients with possible seizures.

general neurocritical care practices

- Aggressive fever management, with physical cooling if needed.

- Avoid hyponatremia (with aggressive treatment if this occurs).

- Target normocapnia (check blood gas & trend etCO2 if intubated).

- Chemical DVT prophylaxis is initially contraindicated; use sequential compression devices until the aneurysm is protected.

- Follow magnesium with daily labs & replete PRN.

SAH grading:

epidemiology*

*For an outstanding resource on Subarachnoid Hemorrage Imaging, see Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Dr Mostafa El-Feky and Assoc Prof Frank Gaillard et al. Radioaedia [accessed 7-6-2021].

Note that you can search Radiopaedia for articles [116] related to subarachnoid hemorrhage, cases [191], and other resources.

general

- Nontraumatic SAH causes ~3% of all strokes.(30516599)

- The age range is broad. With an average age of only 50, SAH affects younger patients more often than most other stroke types.

- Stronger risk factors for aneurysmal SAH include:

- Hypertension, smoking, alcoholism.

- Personal or family history of SAH or another aneurysm.

- Genetic diseases, including polycystic liver/kidney disease, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and sickle cell disease.

- Sympathomimetic use (e.g., cocaine, amphetamine).

causes of SAH

- 85% are aneurysmal.

- 10% are perimesencephalic hemorrhages.

- 5% have other causes, including:

- Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), dural arteriovenous fistula.

- Cerebral sinus vein thrombosis (CSVT).

- Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS).

- Arterial dissection.

- Trauma.

- Pituitary apoplexy.

- Vasculitis.

- Sympathomimetic use.

CT angiography

- CT angiography (CTA) is highly sensitive and specific (~95%) for aneurysm detection, but may miss very small aneurysms.

- CTA has numerous potential roles:

- (1) For patients who have a SAH, CTA is essential to evaluate for underlying vascular anomalies (e.g., aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations).

- (2) For patients who do not have a SAH, CTA is useful to evaluate for the possibility of Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome (RCVS) or cervical artery dissection.

- (3) For patients with a thunderclap headache and possible SAH, the finding of an aneurysm may indicate the need for further diagnostic testing (e.g., with lumbar puncture).

- Based on increasing appreciation of the prevalence of RCVS among patients with thunderclap headache, such patients may benefit from CTA regardless of whether the noncontrast CT scan is positive for SAH.

- Broader use of CTA may also be bolstered by evidence that contrast dye is not nephrotoxic.

- A potential drawback of CTA is that it may reveal asymptomatic unruptured aneurysms in ~2% of the population. Thus, it must be borne in mind that detecting an aneurysm without subarachnoid blood is not diagnostic of an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. However, detecting unruptured aneurysms may provide an opportunity to advise patients regarding practices that could reduce their risk of aneurysmal rupture in the future (e.g., blood pressure control, tobacco cessation, avoidance of excessive alcohol use, and avoidance of sympathomimetics).

lumbar puncture

A traumatic tap is common and often cannot be differentiated from SAH in part because most clinical laboratories do not have validated spectrophotometry. -Maher M et al. (31964292)

- Traditionally, LP has been used to evaluate for SAH in patients with negative noncontrast head CT scan who have high suspicion for SAH (primarily if the CT scan was obtained >6 hours after headache onset). In this context, erythrocytes or xanthochromia would support a diagnosis of SAH.

- Lumbar puncture suffers from numerous drawbacks, including:

- LP is an invasive procedure with risks of infection and hematoma.

- LP can be technically challenging in some patients.

- LP is contraindicated in patients with coagulopathy or therapeutic anticoagulation.

- LP is time-consuming, delaying the diagnosis of SAH.

- The performance of LP is far from perfect, with sensitivity and specificity in the 85% range.

- It’s unclear how to optimally differentiate between SAH and a traumatic LP (falling numbers of RBCs from tube #1 to tube #4 can be seen with both a traumatic tap and a SAH; various articles disagree about optimal RBC cutoffs for tube #4).

- The use of LP for diagnosis of SAH is controversial.(34030777) The routine use of LP is gradually falling out of favor, primarily for two reasons:

- (1) With ongoing, perpetual improvements in CT scanning technology, fewer hemorrhages will be missed by CT scan. The seminal Perry study showing that CT scan sensitivity decreased after six hours was performed between 2000-2009.(21768192) CT scanners have improved a lot in the past fifteen years, so this data probably doesn’t apply to modern scanners.

- (2) There is increasing recognition that many patients with thunderclap headache have RCVS, a diagnosis that requires CT angiography. Thus, patients presenting with thunderclap headache may benefit from CT angiography even if the LP is negative. Such patients may be better served by receiving both a CT and CTA immediately. If both the CT and CTA are negative, then SAH can be safely excluded.(30881537)

- In some patients, LP may be required to exclude CNS infection (e.g., patients presenting with a more gradual-onset headache, or other features suggestive of infection).

MRI & MRA

- MRI/MRA overall has similar performance compared to CT +/- CTA. However, MRI is limited by logistic constraints as the initial diagnostic test.

- (1) Diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage:

- FLAIR is sensitive in the acute phase of SAH, showing sulcal hyperintensity.(31485117)

- Sequences that detect hemosiderin (GRE and SWI) may be better than CT scan for subacute or chronic SAH.(30516599) These sequences become more sensitive for SAH detection over a period of days, rendering MRI a potentially attractive option for patients who present late and have a negative CT scan.

- (2) Detection of underlying pathology:

- MRI can be useful to detect subtle underlying pathology (e.g., arteriovenous malformations, infections, malignancy, or inflammatory disorders).(30516599)

- For patients with SAH near the base of the brain and no defined source of bleeding, cervical spine MRI may be useful to evaluate for a spinal source of bleeding.

invasive angiography

- (1) Diagnostic role:

- Invasive angiography is the gold standard for detection of aneurysms or cerebral vasospasm.

- For patients with a SAH and no evidence of an aneurysm on CT angiography, an invasive angiogram may be performed to further exclude the presence of aneurysms or other vascular causes of bleeding.

- (2) Interventional role:

- Following initial SAH diagnosis, angiography may allow for interventional coiling of aneurysms, to prevent rebleeding.

- For patients with post-SAH vasospasm, angiography may allow for local infusion of vasodilators and angioplasty.

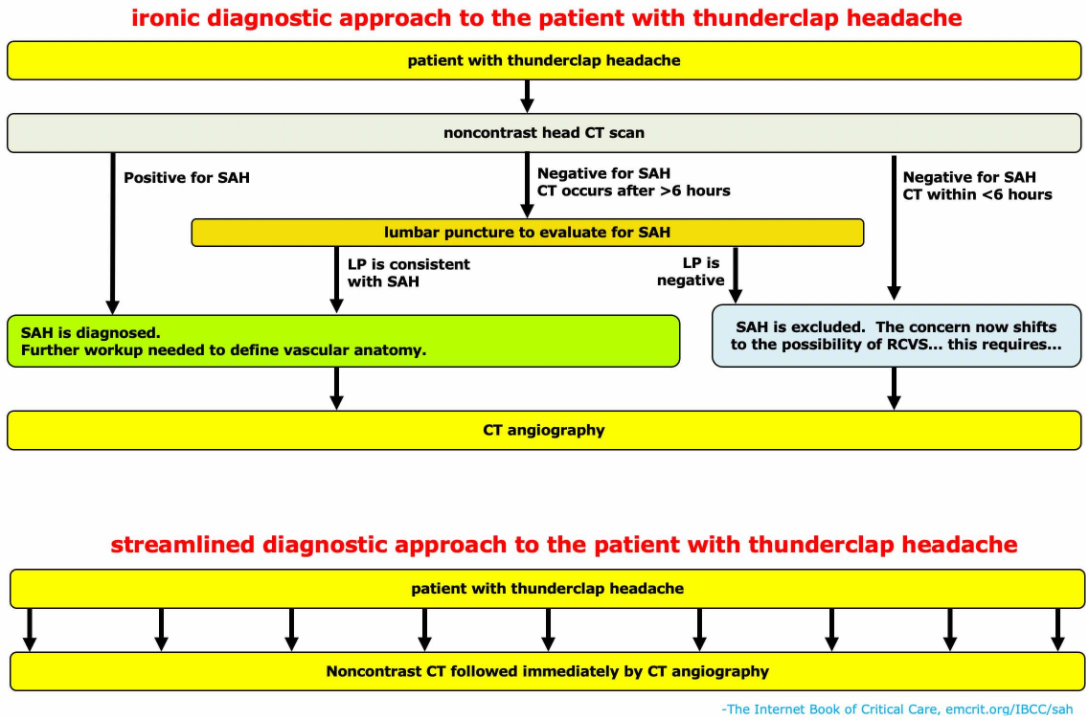

overall diagnostic algorithm

- For patients with thunderclap headache, a reasonable diagnostic strategy might be to perform a STAT noncontrast CT scan followed immediately by a CTA. CT/CTA is fast, noninvasive, and safe (remember that contrast nephropathy doesn’t exist). This combination provides an immediate wealth of information about possible diagnostic possibilities (especially SAH, RCVS, arterial dissection, arteriovenous malformation, or intraparenchymal hemorrhage). For patients with SAH, immediate vascular imaging will help fast-track patients to prompt neurointervention, to prevent rebleeding.

- If CT/CTA leaves remaining confusion about the possibility of SAH, then lumbar puncture and/or MRI/MRA may be considered. MRI may be especially useful if there is concern regarding other underlying brain or cervical spine pathology, such as CNS vasculitis or malignancy.

- Traditionally, the approach to thunderclap headache has focused narrowly on ruling SAH in or out. As we learn more about other vascular pathologies (e.g., cervical arterial dissection and RCVS), it’s becoming clear that simply evaluating for SAH isn’t enough for these patients. With ongoing improvements in CT scanning technology, a CT/CTA strategy may offer patients a rapid evaluation for numerous vascular pathologies – not just “rule-out SAH.”