In addition to the resources below please see and review Rapid infusion catheter from WikiEM. This resource is great. Review it first!

In this post, I link to and embed a video on The Rapid Infusion Catheter. I also excerpt from a blog resource on a potentially disastrous insertion error.

Links to and excerpts from Perils and Pitfalls With the Rapid Infusion Catheter (RIC), Eric McDaniel, MD; Roy Kiberenge, MD; Robert Gould, MD, February 2020. From the APSF Newsletter (Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation).

SUMMARY:

Rapid infusion catheters (RIC) are useful for patients requiring prompt, large volume fluid resuscitation. This high-flow, low-resistance device may be readily inserted in a large peripheral vein via a standard guidewire/dilator/catheter insertion technique. However, like all invasive devices, its introduction must follow standard procedures to avoid errors and risks of infiltration or patient injury.

Introduction

The rapid infusion catheter (RIC) is a device used to convert standard peripheral intravenous (PIV) access into a large-volume resuscitation portal.1 The placement of this large-bore (8.5F) intravenous catheter is performed in clinical scenarios where clinicians anticipate the need for large volume resuscitation, and in our case, in preparation for a liver transplantation. This case illustrates once again how inexperience or unfamiliarly with invasive devices such as this “simple” intravenous catheter has the potential for perioperative complications and significant patient injury.

Case Description

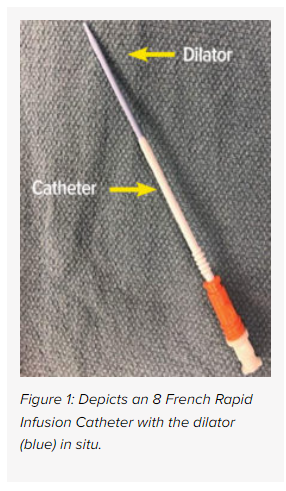

A 47-year-old man with past medical history of atrial fibrillation and hepatocellular carcinoma presented for a deceased donor liver transplant. After an uneventful induction of general anesthesia, we inserted an 8.5 French Rapid Infusion Catheter (RIC) (Figure 1) in anticipation of large-volume resuscitation. A standard technique was utilized for RIC insertion; i.e., a 20G peripheral intravenous (PIV) catheter was initially inserted in the right antecubital brachial vein, providing access for the RIC guidewire. The RIC vein dilator/8.5 F catheter assembly was then advanced to its normal position within the vein. To confirm venous placement, intravenous tubing was connected to the dilator hub to transduce vascular pressure and confirm venous placement. However, contrary to normal insertion procedures, the operator then failed to remove the venous dilator, and incorrectly attached one limb of the rapid infusion system tubing directly to the RIC dilator (Figure 2). The rapid infusion system ran smoothly, and high-pressure alarms were not triggered despite infusion rates up to 400 mL/min. Patient positioning was reconfirmed throughout the extended operation, and no swelling, edema, or signs of vascular extravasation were noted in the affected limb. It was only upon transport to the ICU the next day that the right arm was noted to be edematous secondary to an infiltration associated with the RIC dilator. The RIC system was removed, and the dilator was confirmed to have been left in place within the 8.5 F catheter itself.

Discussion

The preloaded dilator-catheter assembly of the RIC system allows for efficient large bore peripheral venous access in patients. However, its pre-assembled dilator/catheter design led to a misunderstanding by the anesthesia professional in this case; thus, the entire assembly was incorrectly left in vivo. The Luer-lock connection to the vascular dilator was interpreted as “confirmation” of this (erroneous) assumption of where to connect the IV tubing. A subsequent root cause analysis (RCA) determined four contributing factors:

- a lack of operator knowledge, skill, and experience with RIC insertion,

- the supervising anesthesiologist was distracted by two concurrent invasive procedures,

- the preloaded dilator on the RIC was devoid of any label warning it must be removed prior to transfusion, and

- the ability to successfully connect intravenous tubing to the dilator itself.

We were fortunate that this event resulted in no permanent injury to the vascular system or soft tissue of the arm.2 However this incident could have been catastrophic given that the system was attached to a high-volume, positive-pressure fluid infusion pump. Medical centers and departmental directors should ensure adequate education of all OR staff and anesthesia professionals whenever new or novel devices are introduced into the clinical arena.