In addition to this post and resource, please see Links To And Excerpts From “How to Interpret and Pursue an Abnormal Complete Blood Cell Count in Adults” With Additional Resources

Posted on August 20, 2019 by Tom Wade MD

And see also Dx Schema – Lactate Dehydrogenase – LDH from the Clinical Problem Solvers.

In this post I link to and excerpt from How we evaluate and treat neutropenia in adults [PubMed Abstract] [Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF]. Blood. 2014 Aug 21;124(8):1251-8; quiz 1378.

Here are excerpts from the above:

Introduction

Isolated neutropenia without concomitant anemia or thrombocytopenia is a common clinical problem seen by primary care physicians and hematologists. The etiologies of neutropenia vary from transient suppression by self-limited viral illnesses to previously undetected congenital syndromes to serious systemic diseases. The clinical significance likewise ranges from a mild laboratory abnormality with no detectable consequence to a severe disorder characterized by recurrent, life-threatening infections. Consequently, determining how

extensive an evaluation is necessary and whether intervention is

required can be challenging. This review discusses the evaluation and management of the neutropenic adult patient, as well as the pathophysiology of specific neutropenia syndromes.Differential Diagnosis

Congenital neutropenias

Newly detected neutropenia in a young patient, particularly one

without known previously normal ANCs, raises the possibility of an occult congenital neutropenia syndrome (Table 1). These can be divided into pure neutropenic syndromes and congenital syndromes that include neutropenia as a component of their phenotypes. Of the pure neutropenic syndromes, benign familial, and constitutional neutropenia are universally mild and do not lead to infectious sequelae, whereas patients with severe congenital neutropenia (SCN) have extremely low neutrophil counts or frank agranulocytosis, leading to

chronic, severe infections.

For more details on the above see p 1252 + 1253.

Acquired Neutropenias

Acquired neutropenias are more common than congenital neutropenias. They can be seen after infections or after exposures to certain drugs, in the setting of autoimmunity, nutritional deficiency, or hypersplenism, or as a consequence of a hematologic malignancy.

In addition, a significant number of patients with neutropenia have chronic idiopathic neutropenia.

Postinfectious neutropenia is most commonly seen in children

after viral infections. It can be caused by almost any viral infection, though it is most commonly seen after varicella, measles, rubella, influenza, hepatitis, Epstein-Barr virus, or HIV infection. Although most are self-limited, neutropenia after Epstein-Barr virus33 and HIV34 infection can sometimes be prolonged.Bacterial infections are a rarer cause of significant neutropenia, with notable exceptions including Brucella, rickettsial, and mycobacterial infections.

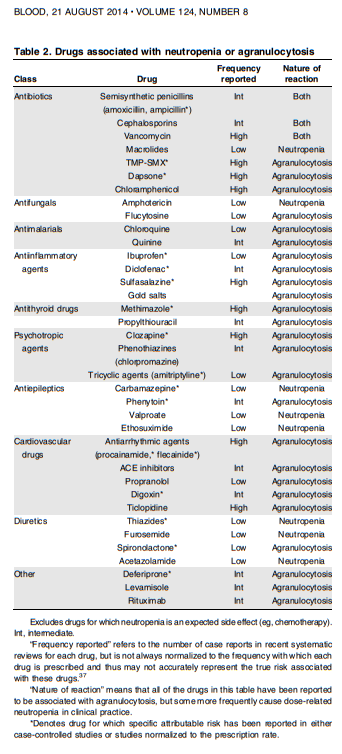

Drugs and toxins are among the most common causes of acquired neutropenia.36 Neutropenia has been reported in association with an extensive array of medications (Table 2). However, certain common offenders bear specific recognition. The most obvious are chemotherapeutic drugs, many of which cause bone marrow suppression as an expected consequence of their mechanisms of action.

One must differentiate mild, dose-related neutropenia from

idiosyncratic agranulocytosis. The true incidence of mild dose related neutropenia can be difficult to estimate accurately for any drug, because most systematic reviews have focused exclusively on agranulocytosis.However, the distinction is clinically important, because patients with drug-induced agranulocytosis frequently present with acute febrile illness or sepsis, whereas most cases of drug-induced neutropenia in the outpatient setting are mild, dose-related, and of minimal concern.

Patients with mild neutropenia can typically continue treatment if the drugs are otherwise improving their symptoms.

In contrast, patients who develop early neutropenia

while taking drugs known to cause agranulocytosis at high rates (eg, clozapine, methimazole) should discontinue taking the drug immediately.Diet and Substance Use

Patients with severe caloric malnutrition (eg, patients with anorexia nervosa) can be leukopenic, but this is usually mild. Patients with folate or vitamin B12 deficiency can be neutropenic, but this rarely occurs without concomitant macrocytosis and pancytopenia. Copper deficiency, a less common cause of leukopenia, has some clinical features that overlap with those of B12 deficiency and is most commonly found in patients who have undergone certain types of

gastric bypass surgery.[Autoimmune Neutropenias]

Autoimmune neutropenia can occur either in isolation42 or in

association with systemic autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). It is caused by autoantibodies directed at specific neutrophil antigens.43 Most of these antigens are surface glycoproteins, including FcgIIIb, CD177, CD11a, and CD11b.44Primary autoimmune neutropenia* usually occurs during the first year of life. As the name implies, it manifests without other signs or symptoms of an underlying autoimmune disorder.46

*See Links To And Excerpts From “Diagnosis and management of primary autoimmune neutropenia in children: insights for clinicians”

Posted on September 21, 2020 by Tom Wade MD

Secondary autoimmune neutropenia is seen primarily in adults

and usually occurs within the context of systemic autoimmune

disease. Autoimmune neutropenia is frequently a benign disorder that manifests as mild neutropenia, and in the setting of systemic autoimmune disease is a manifestation of the activity of the underlying disorder. It seldom needs treatment, but it often responds to either steroids or intravenous immunoglobulin when they are used to treat other concomitant autoimmune symptoms.48 As with other types of neutropenia, the indication for treatment is based on the presence of recurrent infections in the setting of an ANC < 500. A special case is neutropenia in association with large granular lymphocytes, which is typically more severe (discussed later).Chronic idiopathic neutropenia

Neutropenia that is acquired in adulthood but eludes a specific

diagnosis is termed chronic idiopathic neutropenia (CIN). It is a

diagnosis of exclusion that can only be made after a thorough and unrevealing search for other causes, including negative testing for autoimmune disease and nutritional deficiency and a normal bone marrow examination with normal cytogenetics. Its pathogenesis is unknown.Initial triage of the neutropenic adult

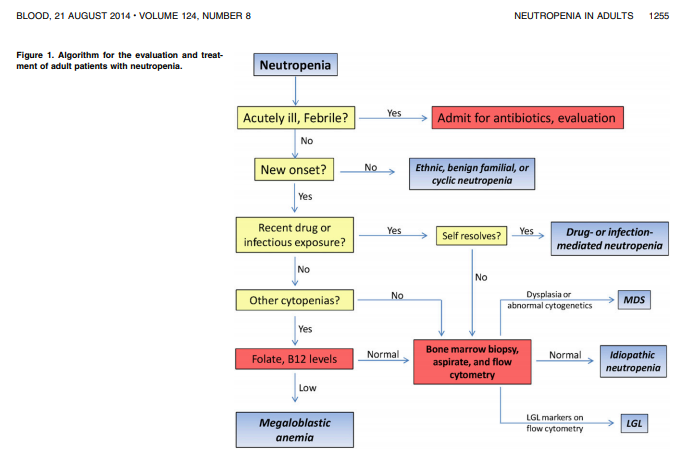

Before initiating an evaluation of newly discovered neutropenia in an adult patient, clinicians should consider a fundamental question: Is the patient acutely ill? Evaluation and treatment of an acutely ill patient not previously knownto be neutropenicis a medical emergency (Figure 1). Patients are progressively at greater risk of serious infections with worsening neutropenia, with patients whose ANC is < 500 at the greatest risk. Such patients who also have a fever > 100.4°F should be admitted immediately to the hospital.

After obtaining appropriate cultures, they should then be started on intravenous antibiotics that empirically cover Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacteria. Patients with less severe neutropenia may still warrant hospitalization and empiric antibiotics if their presentation suggests a serious infection, and clinicians should recognize that what appears to be mild or moderate neutropenia may be an early point on a downward curve toward severe neutropenia or

agranulocytosis.

Neutropenia discovered in the setting of acute illness is immediately concerning, particularly if the symptoms are associated with new recurrent infections or symptoms suggesting an underlying hematologic or rheumatologic disorder. On the other hand, neutropenia discovered on a routine blood count in an otherwise healthy individual is usually benign, although additional evaluation must always be considered before making that determination.

Outpatient evaluation of neutropenia

The evaluation of neutropenia in the outpatient referral population may lack the urgency of an inpatient evaluation but is often considerably more challenging.

The pattern of recent or recurrent infections may help define

both the duration and clinical significance of neutropenia.Recurrent infections in patients with chronic neutropenia are uncommon unless the ANC is < 500/mL and are usually seen only if the ANC is < 200/mL.

In otherwise healthy patients with incidental neutropenia, the

physical examination should focus on examination for adenopathy or splenomegaly, as well as specific signs of active or prior infection, such as healing skin ulcers or aphthous ulcers.All patients with neutropenia should have a CBC panel with

manual smear done and preferably reviewed by a hematologist or hematopathologist, as well as chemistry panels and measurements of liver and renal function. For patients with minimal or no symptoms of infection or other illnesses, serial CBC panels over a period of days or weeks may establish a trend in the neutrophil count.[Note that] a steadily declining ANC is not characteristic of most benign neutropenic syndromes and suggests ancunderlying infectious, autoimmune, or neoplastic cause that requires further evaluation.

ANA and rheumatoid factor are good initial screening tests for

diagnosing systemic rheumatologic disease, and the erythrocyte

sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein number can be useful for detecting underlying inflammation. Even in the absence of obvious lymphocytosis or a history of autoimmune disease, all patients should have peripheral blood flow cytometry to evaluate for LGL. Finally, all patients with neutropenia should have an HIV test done if one has not been performed recently.ANA and rheumatoid factor are good initial screening tests for

diagnosing systemic rheumatologic disease, and the erythrocyte

sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein number can be useful for detecting underlying inflammation. Even in the absence of obvious lymphocytosis or a history of autoimmune disease, all patients should have peripheral blood flow cytometry to evaluate for LGL [Large Granular Lymphocytes]. Finally, all patients with neutropenia should have an HIV test done if

one has not been performed recently.One question that arises is whether to test for the presence of

antineutrophil antibodies, which can be found in some cases of both autoimmune disease–associated or idiopathic neutropenia.[For all of the reasons detailed in the article about antineutrophil antibodies] we rarely encounter a circumstance in which antineutrophil antibodies are helpful, and rarely, if ever, check them in the scope of our usual clinical practice.

Bone marrow aspiration and core biopsy should be considered in all patients with unexplained neutropenia to establish that there are no signs of dysplasia, cytogenetic abnormalities, or involvement by a neoplastic process such as leukemia, lymphoma, or myeloma.

However, in patients with a long history of mild isolated neutropenia, the results of bone marrow aspiration and biopsy are nearly uniformly inconclusive, deeming the procedures probably unnecessary.

In particular, marrow examination is not necessary to diagnose lymphoma or LGL, which can both be detected by flow cytometry of the peripheral blood (marrow infiltration with lymphoma sufficient to cause neutropenia should be detectable by peripheral blood flow).

Management of the neutropenic patient

The majority of the disorders discussed here fall into 2 groups: those that require no treatment (constitutional neutropenia, familial neutropenia, most cyclic neutropenias), and those secondary disorders whose management is outside the scope of this review.