In this post I link to and excerpt from Dr Josh Farkas’ Internet Book Of Critical Care [Link is to the TOC] Diabetic Ketoacidosis – Anatomy of a DKA Resuscitation of Nov 6, 2016:

[Each of the links below are direct links to that section of the IBCC podcast and show notes.]

contents

- definition & diagnosis of DKA

- anatomy of a DKA resuscitation

- special situations

- checklist

- podcast

- questions & discussion

- PDF of this chapter (or create customized PDF)

Here are excerpts:

definition & diagnosis of DKA

Anion Gap = Na – Cl – Bicarb

defining anion gap

- Using this formula, an elevated anion gap is above 10-12 mEq/L.1

- Please don’t correct for albumin, glucose, or potassium. Don’t make this unnecessarily complicated.2

gold-standard definition of DKA?

- Many definitions of DKA may be found in the literature, most of which are antiquated. According to the Canadian DKA guidelines, “there are no definitive criteria for the diagnosis of DKA.”3

- My preferred definition: any patient with diabetes plus a significantly elevated serum beta-hydroxybutyrate level (>3 mM/L).4 5

- Please note the following:

- DKA patients can have a normal glucose (euglycemic DKA, more on this below).

- DKA patients can have a normal pH and a normal bicarbonate. This usually occurs due to a combination of ketoacidosis plus metabolic alkalosis from vomiting.

- That’s right: DKA patients can have a totally stone-cold normal ABG.

various ways to diagnose DKA

- Obvious DKA:

- Patient has known diabetes.

- Anion gap is >>12 mEq/L with positive urinary ketones.

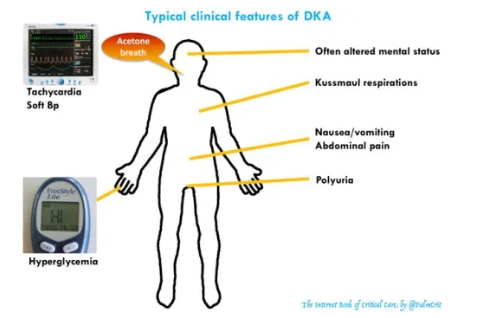

- History & physical exam are consistent with DKA (figure above) and don’t suggest that anything else is going on

- Non-obvious DKA: In situations where the diagnosis is unclear, check lactate and beta-hydroxybutyrate levels.

- A significantly elevated beta-hydroxybutyrate level strongly supports the diagnosis of DKA.6

- If the patient has a markedly elevated anion gap with only a mildly elevated beta-hydroxybutyrate level, consider the possibility that something else is going on (e.g. mild DKA plus toxic alcohol poisoning).

ABG/VBG is neither required nor particularly helpful

- If you look throughout this chapter, neither pH nor pCO2 are mentioned much. These aren’t required for the diagnosis or management of DKA.

- As explored above, DKA is diagnosed purely on the basis of venous blood chemistries (chem-7, anion gap, and if necessary beta-hydroxybutyrate).

- The vast majority of DKA patients can be diagnosed and managed perfectly without ever checking an ABG or VBG.7

step 1- evaluation

precipitating cause

DKA is occasionally the initial manifestation of diabetes, but it usually occurs in the context of known diabetes plus a trigger. Most triggers of DKA are benign (e.g. noncompliance, viral gastroenteritis). However, DKA can be caused by any source of physiologic stress. Occasionally, DKA is the presentation of a serious underlying problem, such as occult sepsis. Common causes of DKA include:

- Insulin non-adherence, inadequate dosing, or insulin pump failure

- Infection (e.g. gastroenteritis, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, diabetic foot infection)

- Pancreatitis

- Pregnancy

- Trauma, surgery

- Substance abuse or alcoholism

- Medications (e.g. steroid, atypical antipsychotics, sympathomimetics, SGLT-2 inhibitors, HIV protease inhibitors, anti-calcineurin immunosupressives8)

evaluation for the cause of DKA

- History and physical examination are the key here. If there is clear history of non-adherence, a big workup isn’t necessary.

- Infectious trigger?

- DKA itself may cause leukocytosis, so a WBC elevation alone is nonspecific.

- Infection is suggested by fever, bandemia (>10%), marked left-shift, or severe leukocytosis (>20,000-25,000).9 10

- Primary abdominal problem?

- DKA itself can cause abdominal pain. This creates diagnosis confusion – we must sort out whether the pain is due to DKA, or whether the pain represents an underlying problem (appendicitis, cholecystitis, etc). This may be sorted out in two ways:

- (1) Severe pain with only mild ketoacidosis argues against DKA causing the pain.11

- (2) When in doubt about the need for an abdominal CT scan, agressively treat the DKA and follow serial abdominal examinations. If the abdominal pain is due to DKA, it will resolve as the ketoacidosis improves. If pain fails to resolve or gets worse, then further investigation is warranted.

- Primary neurologic problem?

- DKA itself cause mental status changes, but this usually occurs when the calculated serum osmolality is >320 mOsm/kg. Abnormal mental status despite normal serum osmolality should trigger suspicion for a primary neurologic problem (e.g. meningitis, intracranial hemorrhage).12

- Another sign of a primary neurologic problem is if the mental status doesn’t improve with treatment of the DKA.13

initial evaluation panel

- EKG

- Electrolytes (including Ca/Mg/Phos), blood count

- If diagnosis of DKA is unclear: beta-hydroxybutyrate level & lactate

- If infection possible: blood cultures, urinalysis, chest X-ray

- If pregnancy is possible: urine pregnancy test or serum beta-HCG

- If significant abodminal pain/tenderness: lipase (note, however, that DKA itself can increase lipase substantially)14

- Troponin level only if EKG or history suggests ischemia (i.e., if you are genuinely concerned about MI).

- Routinely checking troponin on every DKA patient is a common cause of mass hysteria and unnecessary evaluations.

- Additional workup as clinically appropriate (e.g. toxicology evaluation, CT scan to evaluate for septic focus).

The above from Dr. Farkas DKA Chapter is what you need to recognize and diagnose Diabetic Ketoacidosis. [Note to myself]

Dr. Farkas DKA Chapter has detailed treatment information for which you need to go directly there. [Note to myself]