In this post, I link to and excerpt from Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Silent Cerebrovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association [PubMed Abstract] [Full-Text HTML] [Full-TextPDF]. Stroke. 2017 Feb;48(2):e44-e71.

The above article has been cited by 84 articles in PubMed Central.

All that follows is from the above article.

Abstract

Two decades of epidemiological research shows that silent cerebrovascular disease is common and is associated with future risk for stroke and dementia. It is the most common incidental finding on brain scans. To summarize evidence on the diagnosis and management of silent cerebrovascular disease to prevent stroke, the Stroke Council of the American Heart Association convened a writing committee to evaluate existing evidence, to discuss clinical considerations, and to offer suggestions for future research on stroke prevention in patients with 3 cardinal manifestations of silent cerebrovascular disease: silent brain infarcts, magnetic resonance imaging white matter hyperintensities of presumed vascular origin, and cerebral microbleeds. The writing committee found strong evidence that silent cerebrovascular disease is a common problem of aging and that silent brain infarcts and white matter hyperintensities are associated with future symptomatic stroke risk independently of other vascular risk factors. In patients with cerebral microbleeds, there was evidence of a modestly increased risk of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage in patients treated with thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke but little prospective evidence on the risk of symptomatic hemorrhage in patients on anticoagulation. There were no randomized controlled trials targeted specifically to participants with silent cerebrovascular disease to prevent stroke. Primary stroke prevention is indicated in patients with silent brain infarcts, white matter hyperintensities, or microbleeds. Adoption of standard terms and definitions for silent cerebrovascular disease, as provided by prior American Heart Association/American Stroke Association statements and by a consensus group, may facilitate diagnosis and communication of findings from radiologists to clinicians.

Introduction

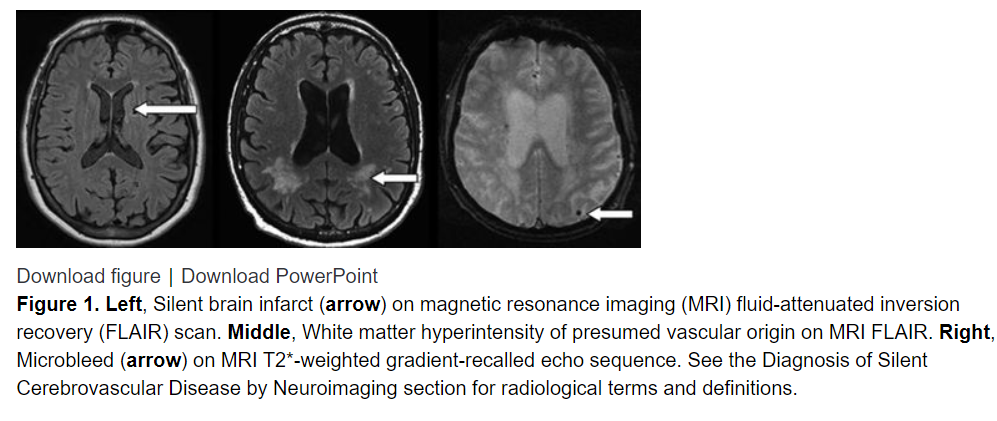

Neuroimaging signs of silent cerebrovascular disease are highly prevalent in older people. Although many radiological manifestations and secondary consequences are now known, the best-defined manifestations—in terms of radiological definition, prevalence, and clinical associations—are silent brain infarcts, white matter lesions of presumed vascular origin, and microbleeds (Figure 1). Approximately 25% of people >80 years of age have ≥1 silent brain infarcts.1 The prevalence of silent cerebrovascular disease exceeds, by far, the prevalence of symptomatic stroke. It has been estimated that for every symptomatic stroke, there are ≈10 silent brain infarcts.2 As a result of this high prevalence, silent cerebrovascular disease is the most commonly encountered incidental finding on brain imaging.3

Two decades of research has generated important insights into the prevalence, manifestations, risk factors, and consequences of silent cerebrovascular disease.4 Silent brain infarcts, also called silent strokes in the literature, are subcortical cavities or cortical areas of atrophy and gliosis that are presumed to be caused by previous infarction.1 White matter lesions of presumed vascular origin represent areas of demyelination, gliosis, arteriosclerosis, and microinfarction presumed to be caused by ischemia.4 They may be visible as areas of white matter hyperintensity (WMH) on magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (MRI) or white matter hypodensity on computed tomography (CT). Microbleeds are thought to represent small areas of hemosiderin deposition from previous silent hemorrhages and are visible only on MRI sequences optimized for their detection.5 A previous statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) on the definition of stroke includes, for the first time, definitions of silent brain infarcts and silent brain hemorrhages as manifestations of cerebrovascular disease.6

Although often called silent because they occur in the absence of clinically recognized stroke symptoms, population-based epidemiological studies show that these manifestations of cerebrovascular disease are, in fact, associated with subtler cognitive and motor deficits on standardized testing, cognitive decline, gait impairment, psychiatric disorders, impairments in activities of living, and other adverse health outcomes.7–9 Furthermore, both silent brain infarcts and WMHs are associated with future incident cognitive decline and stroke.10–13 Therefore, these lesions are neither silent nor innocuous. Consequently, some have advocated that the term covert cerebrovascular disease is a more appropriate label than silent disease.14 A previous AHA/ASA statement on vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia reviewed the relationship between silent cerebrovascular disease and clinically identified cognitive impairment.15 Salient findings and recommendations in the statement included that a pattern of diffuse, subcortical cerebrovascular pathology, identifiable on neuroimaging, can support a diagnosis of probable or possible vascular cognitive impairment. However, that statement did not offer guidance for stroke prevention.

In this statement, we systematically review the literature on the prevalence of silent cerebrovascular disease and its implications for stroke prevention. Our writing committee identified specific scenarios in which clinical decision making may be influenced by the presence of incidentally detected silent cerebrovascular disease. We conducted focused literature searches to address these clinical questions: (1) How should silent cerebrovascular disease be classified radiologically and reported? (2) What investigations, if any, should be ordered for patients with silent cerebrovascular disease? (3) How should patients with silent brain infarcts or WMHs be managed to prevent symptomatic stroke? (4) What is the safety of medical therapies, including anticoagulation, in patients with cerebral microbleeds (CMBs)? (5) What is the safety of thrombolysis or acute stroke reperfusion therapy in patients with microbleeds? (6) Is there a role for population screening for silent cerebrovascular disease? For each section, we offer suggestions and considerations for clinical practice (summarized in Table 1) and identify areas that require further investigation.

See Table 1. Summary of Suggestions for Clinical Care of Patients With Silent Cerebrovascular Disease

Table 1. Summary of Suggestions for Clinical Care of Patients With Silent Cerebrovascular Disease Diagnosis by neuroimaging MRI has greater sensitivity than CT for diagnosis of silent cerebrovascular disease. Minimum MRI acquisition standards are provided in Table 2. Radiology reports should describe silent cerebrovascular disease according to STRIVE.16 WMHs of presumed vascular origin should be reported with the use of a validated visual rating scale such as the Fazekas scale for MRI.19 Investigations for patients with silent cerebrovascular disease Assess common vascular risk factors and assess pulse for atrial fibrillation. Consider carotid imaging when there is silent brain infarction in the carotid territory. Consider echocardiography when there is an embolic-appearing pattern of silent infarction. Consider noninvasive CT or MR angiography when there are large (>1.0 cm) silent hemorrhages. Prevention of stroke in patients with silent brain infarcts Take a careful history to determine whether the infarction was symptomatic. Implement preventive care recommended by AHA/ASA guidelines for primary prevention of ischemic stroke. The effectiveness of aspirin to prevent stroke has not been studied in this setting. The clinician should be aware that there is an increased risk for future stroke, and it is reasonable to consider this information when making decisions about anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation, revascularization for carotid stenosis, treatment of hypertension, and initiation of statin therapy. However, the clinician should also be aware that the role of silent brain infarcts in these decisions has not been studied in RCTs. Prevention of stroke in patients with WMHs of presumed vascular origin Implement preventive care recommended by AHA/ASA guidelines for primary prevention of ischemic stroke. It is not clear whether WMH alone, in the absence of other risk factors, is a sufficient reason for aspirin therapy. The clinician should be aware that there is an increased risk for future stroke, and it is reasonable to consider this information when making decisions about anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation, revascularization for carotid stenosis, treatment of hypertension, and initiation of statin therapy. However, the clinician should also be aware that the role of WMH burden in these decisions has not been studied in RCTs. Anticoagulation and other therapies in patients with silent microbleeds It is reasonable to provide anticoagulation therapy to patients with microbleeds when there is an indication (eg, AF). When anticoagulation is needed, a novel oral anticoagulant is preferred over warfarin. Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage could be considered as an alternative to anticoagulation. It is reasonable to provide antiplatelet therapy to patients with microbleeds when there is an indication. MRI screening for microbleeds is not needed before the initiation of antithrombotic therapies. Individuals with silent microbleeds are at increased future risk of both ischemic stroke and ICH. Implement preventive care recommended by AHA/ASA guidelines for primary prevention of ischemic stroke. It is reasonable to provide preventive care recommended by AHA/ASA guidelines for prevention of ICH. Safety of acute ischemic stroke therapy in patients with silent microbleeds It is reasonable to administer intravenous alteplase to patients with acute ischemic stroke and evidence of microbleeds if it is otherwise indicated. It is reasonable to perform endovascular thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke and evidence of microbleeds. In acute ischemic stroke patients with microbleeds, bypassing intravenous alteplase therapy to proceed directly to endovascular thrombectomy is an unproven strategy. Population screening Screening the asymptomatic general population with MRI to detect silent cerebrovascular disease is not justified by current evidence. Diagnosis of Silent Cerebrovascular Disease by Neuroimaging

Silent cerebrovascular disease is typically recognized on brain MRI and CT scans. MRI has greater sensitivity and specificity than CT16 and can better demonstrate and differentiate small cortical and subcortical infarction, lacunar infarcts, WMHs, perivascular spaces, brain atrophy, and other structural lesions (Figure 1). CMBs are visible on hemorrhage-sensitive MRI sequences but unapparent on CT.

MRI Acquisition

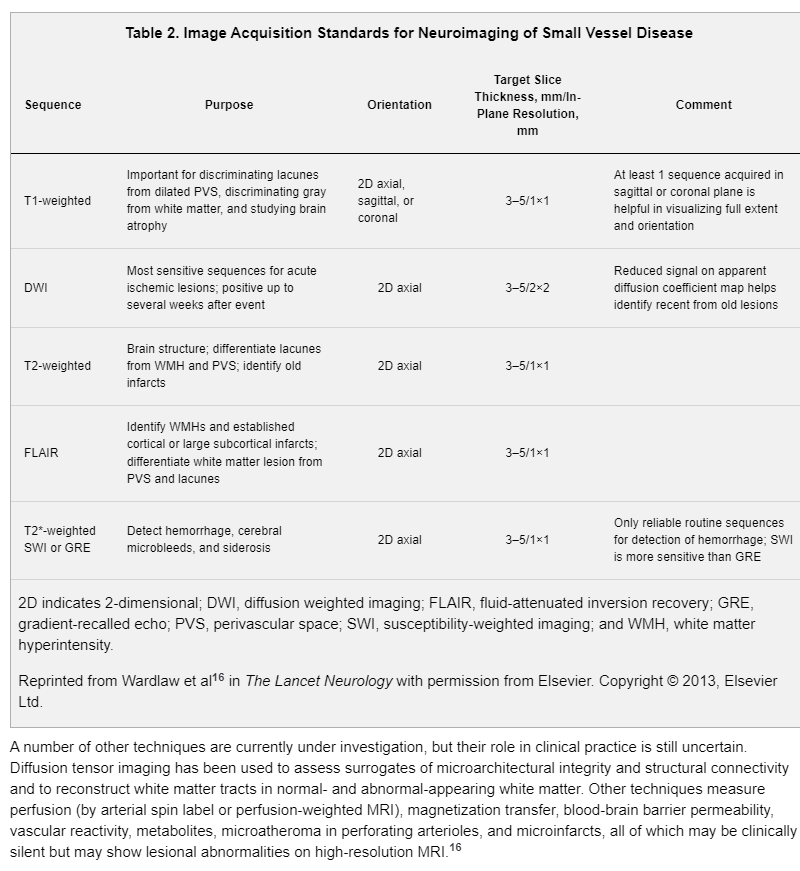

A comprehensive MRI evaluation for silent cerebrovascular diseases should include a minimum of the following sequences: axial diffusion-weighted imaging with both a trace image and an apparent diffusion coefficient map, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), T2-weighted and T2* susceptibility-weighted imaging (or T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo if susceptibility-weighted imaging is not available), and T1-weighted imaging. The diffusion-weighted trace image and apparent diffusion coefficient map are important for identifying recent infarcts. Sequence parameters should be consistent with recommendations for neuroimaging from the American College of Radiologists,20 including that the slice thickness should be ≤5 mm and in-plane resolution should be ≤1×1 mm. For increased sensitivity to small infarcts and microbleeds, slice thickness should ideally be ≤3 mm and slice gaps should be minimized or slices should be acquired with no gaps. Whole-brain coverage in all sequences should be used. Three-dimensional T1-weighted thin-section isotropic sequences can be reformatted to allow coregistration and to quantify brain volume. An MRI field strength of 3.0 T is preferred for higher resolution; however, modern 1.5-T MRI scans are also acceptable.21 In either magnet, brain coils should always be used. Table 2 outlines the proposed MRI acquisition standards for neuroimaging for clinical care or epidemiological studies.16

Consensus Terms and Definitions for MRI and CT Manifestations of Silent Cerebrovascular Disease

Most silent cerebrovascular findings on MRI are related to cerebral small vessel disease. The first neuroimaging consensus document for classification of small vessel disease was proposed in 2006 by the US National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the Canadian Stroke Network as part of the development of standards for research on vascular cognitive impairment.22 More recently, a scientific statement from the AHA/ASA incorporated neuroimaging evidence of cerebrovascular disease for vascular cognitive impairment and dementia.15

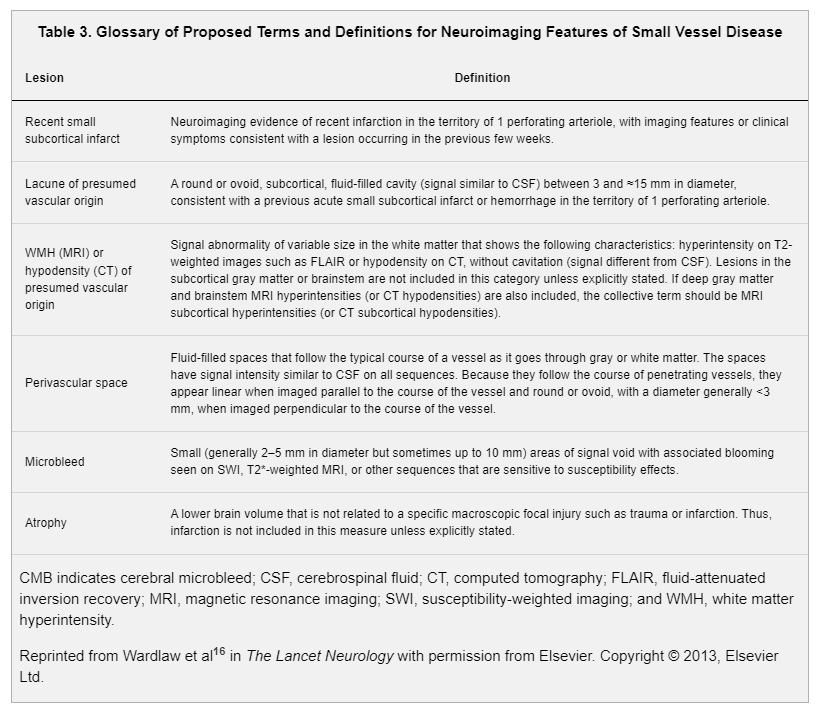

The radiological definitions and terms used to describe silent cerebrovascular disease have varied substantially in research studies and in clinical practice.16,23,24 STRIVE (Standards for Reporting Vascular Changes on Neuroimaging) was an international collaboration to recommend standards for research and to develop definitions and imaging standards for describing signs of small vessel disease on MRI and CT in the context of aging and neurodegeneration (Table 3).16 These terms and definitions apply to currently recognized manifestations of cerebral small vessel disease, which accounts for the majority (85%–90%) of silent cerebrovascular disease. However, a minority (≈10%–15%) of silent cerebrovascular disease is instead manifest as cortical infarcts or larger (>15 mm) subcortical infarcts related to large artery disease, cardioembolism, or other mechanisms rather than small vessel disease.25

Radiological Diagnosis and Reporting of Silent Brain Infarcts, WMHs, and Microbleeds

Silent cerebrovascular disease is typically recognized on brain MRI and CT scans. MRI has greater sensitivity and specificity than CT16 and can better demonstrate and differentiate small cortical and subcortical infarction, lacunar infarcts, WMHs, perivascular spaces, brain atrophy, and other structural lesions (Figure 1). CMBs are visible on hemorrhage-sensitive MRI sequences but unapparent on CT.