In this post I link to and excerpt from the Internet Book of Critical Care [link is to the Table Of Contents] chapter Hypertensive emergency. November 11, 2016 by Josh Farkas

All that follows is from the chapter, Hypertensive emergency

CONTENTS

- Rapid Reference

- Preamble

- Diagnosis & definition

- What is the cause?

- Treatment

- PRES

- Podcast

- Questions & discussion

- Pitfalls

- PDF of this chapter (or create customized PDF)

rapid reference

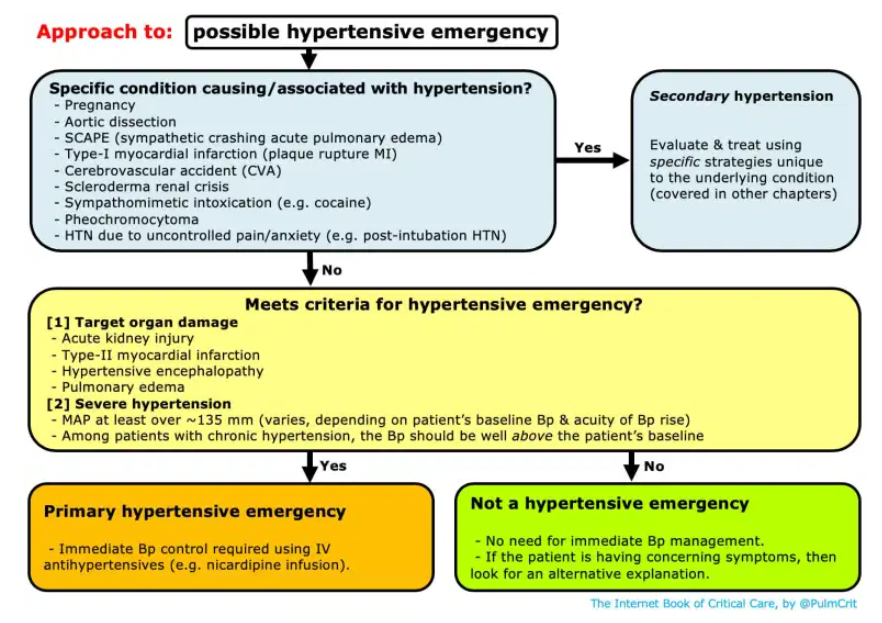

approach to severe HTN:

“secondary hypertension”

- Secondary hypertension is used here to refer to HTN which is a result of some other primary process. In most cases, the primary process will be more obvious clinically, dominating the initial clinical presentation (e.g. aortic dissection, sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema, cocaine intoxication).

- Treatment will vary widely, depending on the specific context. This will be covered in other chapters regarding these individual conditions.

- Please note that the remainder of this chapter doesn’t necessarily apply to secondary hypertension (for example, do not use this as a guide to pregnancy-associated hypertension and pre-eclampsia, which requires an entirely different approach).

Preamble: Use the MAP

Before getting started, it will be useful to define our preferred measurement of blood pressure: the mean arterial pressure (MAP). The MAP is the average arterial pressure, which can be estimated as follows:

MAP = [2(diastolic Bp) + Systolic Bp]/3

There are several reasons that MAP is the preferred measurement of blood pressure, as follows:

Reason #1: MAP is what the automated Bp cuff is actually measuring

- Automated oscillometric Bp cuffs measure the MAP directly (whereas the systolic and diastolic Bp are estimated using proprietary algorithms).

- This could make the MAP the most accurate measurement.

Reason #2: MAP may be most closely related to the risk of hypertensive emergency

- We tend to focus on the systolic blood pressure (“she had a systolic of 250!!”). However, the risk of hypertensive emergency seems overall be more closely related to the diastolic pressure than the systolic pressure.

- MAP is probably the single parameter most closely related to the risk of hypertensive emergency.

Reason #3: MAP is preferred in guiding therapy

- The dosing of any antihypertensive drug can be titrated only against a single variable. The best way to titrate antihypertensive drugs in a logical fashion is to target a specific MAP.

- Trying to titrate an antihypertensive infusion against systolic and diastolic blood pressure simultaneously is often impossible and confusing (for example, what happens if the systolic target is reached but not the diastolic?).

criteria required to diagnose hypertensive emergency

- (1) Severe hypertension

- Usually a MAP of at least >140 mm is needed to cause a hypertensive emergency.

- This may vary considerably depending on the patient’s baseline Bp. Hypertensive emergency can occur at lower MAPs in previously normotensive patients who have acute hypertension (e.g. pregnant women with preeclampsia).1 Alternatively, patients with chronic hypertension may have extremely elevated Bp without hypertensive emergency.

- (2) Target organ damage, such as:

- Acute kidney injury (often with microscopic hematuria)

- Myocardial ischemia (type-II myocardial ischemia).

- This should be a true myocardial infarction, not solely an elevated troponin (more on the definition of myocardial infarction here).

- Pulmonary edema

- Hypertensive encephalopathy (visual disturbance, seizure, delirium). In situations where this is unclear, the presence of increased optic nerve sheath diameter on ultrasonography might support the diagnosis of hypertensive encephalopathy with increased intracranial pressure.

- (Note: Epistaxis, proteinuria, or chronic renal failure don’t qualify as target organ damage.)

if there’s no target organ damage, it’s not an emergency!

- Without target organ damage, it’s not a hypertensive emergency and there is no need for hospital admission.

- (So, there’s certainly no reason to admit the patient to the ICU!)

- In case there is any doubt about this, the following is a verbatim statement of the AHA/ACC guidelines

(29133354).

what is causing the hypertensive emergency?

causes of hypertensive emergency

- Hypertensive emergency is often due to non-adherence to antihypertensive medications.

- Especially withdrawal from clonidine

- If there is no clear trigger for the hypertensive emergency, the possibility of a secondary hypertensive emergency should be considered. Causes include:

- Sympathomimetic drugs (e.g. cocaine, over-the-counter decongestants)

- Other medications (e.g. cyclosporine, tacrolimus, erythropoietin, steroid, NSAIDs)

- CNS event (e.g. ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage)

- Sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema (SCAPE)

- Aortic dissection

- Preeclampsia

- Endocrinopathy (e.g. pheochromocytoma, hyperaldosteronism, Cushing’s syndrome, hyperthyroidism)

- Renal (scleroderma renal crisis, acute glomerulonephritis)

- Volume overload

- Pain, anxiety, urinary obstruction

evaluation for the cause

- EKG

- Bedside ultrasonography

- ? Volume status

- ? Evidence of aortic dissection

- ? Evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy

- ? Pulmonary edema on lung ultrasonography

- Labs

- Basic labs (chemistries, CBC, coagulation studies)

- Troponin (only if EKG/clinical evidence to support MI)

- Urinalysis

- Urine toxicology screen may be considered.

- Non-contrast head CT if presentation is worrisome for possible intracranial hemorrhage

Rx #1- remove exacerbating factors

Blood pressure can be affected by a myriad of factors. Before initiation of antihypertensives, consider some simple interventions which may be highly effective in reducing the blood pressure. Overlooking these factors may eventually lead to overshoot hypotension (e.g. if pain is driving the hypertension but you initiate therapy with antihypertensives first, when the pain eventually resolves the patient may develop overshoot hypotension).

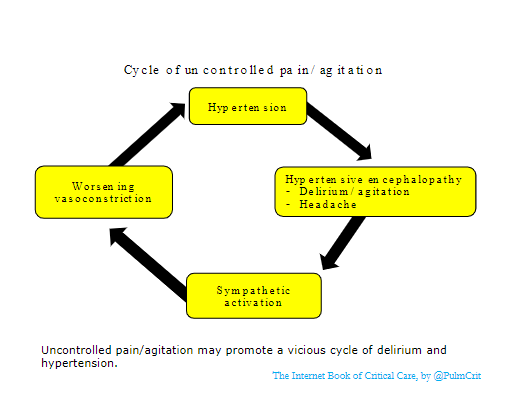

control agitation and/or pain

- Severe pain: manage this immediately (e.g. with IV fentanyl).

- Agitation: agitated delirium itself may lead to sympathetic activation and hypertension. If the patient is severely agitated, treat this immediately (e.g. with intravenous antipsychotic or dexmedetomidine).

- (Hint: Dexmedetomidine is a sympatholytic drug, so it will tend to decrease blood pressure and heart rate. It’s a nice choice for agitated delirium with excessive sympathetic activity.)

volume removal

- Volume overload may cause hypertension, which is relatively difficult to treat using conventional antihypertensives.

- This is most often seen in the following situations:

- Recovery phase following critical illness that was managed with excessive fluid administration.

- Chronic renal insufficiency with accumulation of volume (especially in patients on chronic dialysis).

- Diagnosis of volume overload is based on a combination of clinical history and bedside ultrasonography.

- The preferred treatment is volume removal (either diuresis or dialysis).

- For dialysis patients, a high-dose nitroglycerine infusion may be used as a temporizing measure until hemodialysis is available. As volume is removed with dialysis, the nitroglycerine is weaned off.

Rx #2- IV antihypertensive

blood pressure goal?

- There isn’t solid evidence behind this. The following approach seems reasonable & consistent with guidelines (29133354).

- (#1) The initial goal is to decrease the MAP by ~10-20% within 1-2 hours.

- (#2) If this reduction is tolerated, then decrease the MAP to ~120 mm (e.g. ~160/110 mm) over the next 2-6 hours.

- (#3) The blood pressure may subsequently be gradually decreased further over a period of days, as clinically tolerated.

- These general recommendations may not hold for every patient. Consider what the patient’s baseline pressure is, and how rapid the increase in pressure was.

- For a patient with chronic hypertension, a more gradual approach to lowering the Bp may be wise.

- For a patient with very acute development of hypertension (e.g. postoperatively or due to an acute ingestion), more rapid reduction of Bp may be reasonable.

- Whenever possible, try to clearly define the baseline Bp (e.g. obtain multiple Bp readings in both arms before starting antihypertensives). Lack of a definite baseline Bp leads to uncertainty regarding all downstream Bp targets.

preamble on hypertensive infusions: titratable vs. quasi-titratable vs. bolus

- In general:

- Continuous infusions are used for drugs with a short half-life (e.g. norepinephrine). The short half-life means that the drug needs to be infused continuously. It also makes the drug easily titratable.

- Intermittent boluses are used for drugs with longer half-lives (most drugs).

- Anti-hypertensive drugs can be classified into roughly three groups:

- (1) Truly titratable agents

- Duration of action is <<30 minutes.

- The drug must be given as a continuous infusion. It is fairly easy to titrate.

- Examples: Nitroglycerine, nitroprusside, esmolol, clevidipine.

- (2) Quasi-titratable agents

- Duration of action is <1-2 hours.

- The drug is generally given as a continuous infusion, but it’s a bit sluggish to titrate.

- Examples: Nicardipine, diltiazem.

- (3) Bolus agents

- Duration of action is >1-2 hours

- The easiest way to give the drug is as intermittent bolus doses. If an infusion is used, it will tend to accumulate and be rather difficult to titrate.

- Examples: Labetalol, metoprolol.

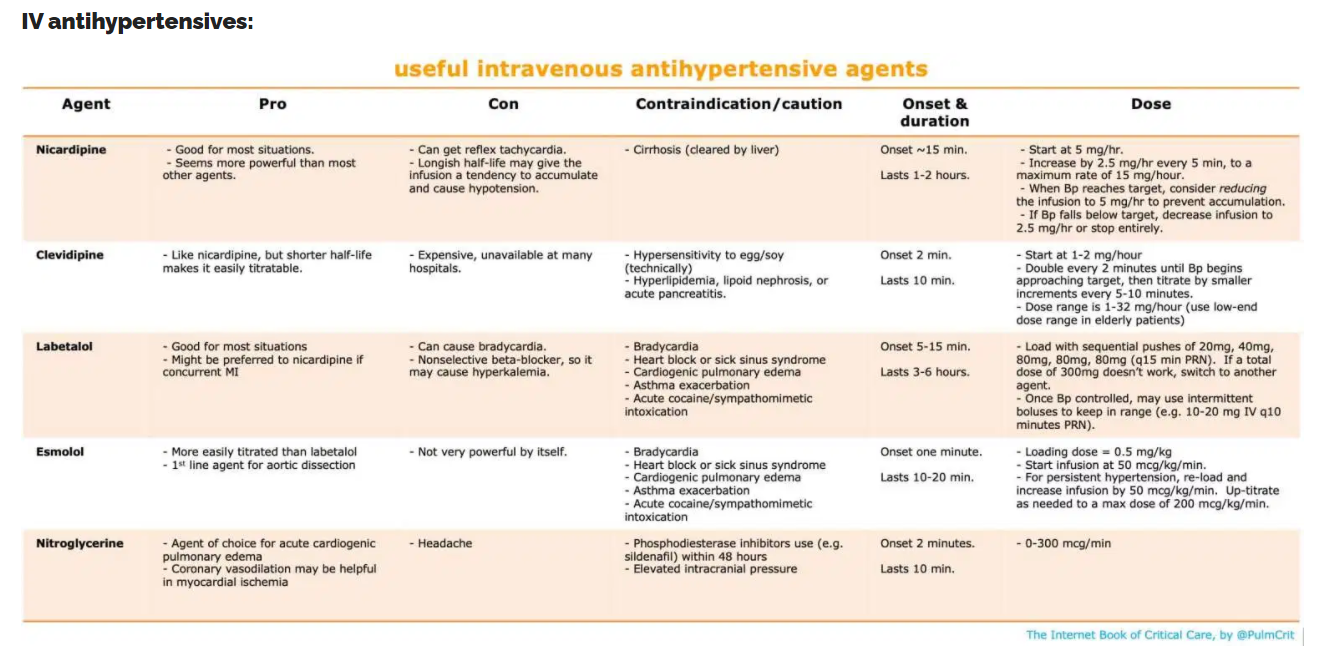

comments on preferred agents

Nicardipine

- Workhorse agent in hospitals that don’t have clevidipine.

- Highly effective and applicable to most scenarios.

- Drawback is that it’s a quasi-titratable agent, so it may accumulate over time and cause overshoot hypotension. One approach to avoid overshooting is to scale back the infusion rate once the target blood pressure is reached. One strategy to avoid this:

- If Bp is above target, increase infusion by 2.5 mg/hr every 5-15 minutes to a maximum rate of 15 mg/hour.

- After the blood pressure reaches target, drop the infusion down to 5 mg/hr.

- If the blood pressure falls below target, drop the infusion down to 2.5 mg/hr.

- If the blood pressure falls substantially below target, stop the infusion entirely.

Clevidipine

- Basically, a next-generation nicardipine with much shorter half-life. This makes clevidipine a truly titratable agent (as defined above).

- Clevidipine has been shown to be more successful than nicardipine at achieving tight blood pressure control.2 It’s easier to use than nicardipine, with a lower risk of overshoot hypotension.

- Clevidipine is unavailable at many hospitals due to cost considerations. If clevidipine could decrease in cost to become competitive with nicardipine, it would probably replace nicardipine as a front-line agent for antihypertensive emergency.

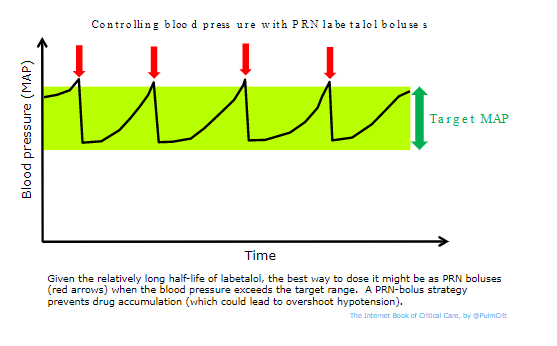

Labetalol

- Good option, especially if you’re trying to drop the Bp by only a moderate amount (e.g. 10-30 mm). For profound hypertension, labetalol may be less effective than nicardipine.

- Labetalol lasts ~2-4 hours, so it doesn’t make sense to give it as a continuous infusion (a continuous infusion will gradually accumulate and eventually cause overshoot hypotension). Although some references recommend using labetalol as a continuous infusion, it may be more of a bolus agent (as defined above).

- One strategy for using labetalol:

- 1) A PRN bolus dose must be found which is sufficient to cause an effective drop in Bp (yet not an excessive drop). The dose varies between patients and must be determined empirically (start with 10 mg and up-titrate as needed until an effective dose is determined).

- 2) The blood pressure must be monitored carefully, with repeat PRN doses used as necessary (figure below).

- Escalating boluses of labetalol can be useful to achieve rapid control of severe hypertension at the bedside if this is needed (e.g. acute Bp spike which requires immediate control).

Esmolol

- Esmolol has a very short half-life, making it a truly titratable agent. This is a potential advantage compared to labetalol.

- Unfortunately, as a pure beta-blocker esmolol lacks the power of nicardipine or labetalol. Thus, esmolol infusion alone may be inadequate for severe hypertension.

- The classic use of esmolol is as a second agent in combination with a vasodilator, to prevent reflex tachycardia.

Nitroglycerine

- Causes predominantly venodilation at lower doses, but causes arterial vasodilation at higher doses.

- Mostly used for patients with myocardial ischemia, heart failure, or volume overload.

- It is a safe agent with a short half-life, which makes it easy to titrate.

drugs which aren’t preferred

Nitroprusside

- Reasons not to use nitroprusside:

- (1) Can increase the intracranial pressure.

- (2) Can cause cyanide toxicity and lactic acidosis – which may create a confusing picture if the patient deteriorates.

- (3) Tends to cause wide swings in the blood pressure (requires continuous close attention and meticulous titration).

- (4) Coronary vasodilation can cause a steal phenomenon that promotes myocardial ischemia.

- Generally, another agent will be equally effective and safer.

- Given lack of any high-quality evidence that tight Bp control improves outcomes, it’s challenging to justify the risks involved with using nitroprusside.

Intravenous hydralazine

- Reasons not to use IV hydralazine

- (1) Effect is unpredictable (sometimes minimally effective, sometimes causes precipitous Bp drop)

- (2) Impossible to titrate (works for 2-4 hours)

- Most situations, another agent will be equally effective and safer (one potential exception is preeclampsia with refractory hypertension).

is an arterial line needed?

- No good data on this.

- Indications for an arterial line might include:

- Discrepant blood pressures in different extremities (in this situation consider aortic dissection)

- Very labile blood pressures

- Profound hypertension (too high to be real?)

- Clinical deterioration despite noninvasive management

- Use of nitroprusside (which, as discussed above, is generally a bad idea)

- My opinion is that an arterial line is unnecessary in most cases of hypertensive emergency.

- The pain of arterial line insertion can exacerbate hypertension.

- No prospective evidence exists to show that this procedure is beneficial or necessary.

- Bp targets are arbitrary and poorly defined. It’s illogical to tightly chase an arbitrary target:

if the blood pressure plummets, evaluate for hypovolemia and volume resuscitate if necessary

- Patients often have a combination of:

- (1) Excessive vasoconstriction, which is driving their hypertension.

- (2) Hypovolemia due to the diuretic effect of hypertension (“pressure diuresis”).

- When treated with vasodilation, these patients may develop hypotension (due to unmasking of their hypovolemia). Overall this may lead to wide fluctuations in blood pressure, which is difficult to control. Stabilizing these patients requires addressing both problems:

- (1) Control hypertension with vasodilation.

- (2) Volume replete to manage hypovolemia (e.g. with guidance of echocardiography).

Pitfalls

- #1 most common mistake = overdiagnosis of hypertensive emergency among patients with scary high Bp but no target organ damage. This isn’t a hypertensive emergency, please don’t call the ICU for this. Thanks in advance.

- #2 most common mistake = treating hypertensive emergency too aggressively and dropping the Bp too much and too fast.

- #3 most common mistake = trying to transition from an antihypertensive infusion to an oral agent that takes a long time to have any effect on blood pressure (e.g. amlodipine). This causes patients to be stuck in the ICU on an infusion forever. It’s also unpredictable when these drugs take effect, so there is a risk of dose-stacking (i.e. you keep up-titrating oral agents and eventually they all kick in simultaneously, causing hypotension).

- Generally avoid IV hydralazine; this has erratic effects and sometimes bottoms out the blood pressure.

- Don’t use IV metoprolol for blood pressure control. Metoprolol isn’t very effective for control of blood pressure, but it will slow down the heart rate. That actually makes matters worse, because then you can’t use labetalol (since the patient is already bradycardic).

Going further:

- EMCrit 190: Emergencies with a side of hypertension

- Hypertensive emergencies (Emergency Medicine Cases, Anton Helman)

- Hypertensive Emergency (WikEM)

The Internet Book of Critical Care is an online textbook written by Josh Farkas (@PulmCrit), an associate professor of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine at the University of Vermont.