Today, I reviewed, excerpt from and link to Evaluation Of The Limping Child [PubMed Abstract] [Download the PDF]. Jessica Burns, MD, MPH; Scott Mubarak, MD

Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, CA. JPOSNA® (the Journal of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America) is an open access journal focusing on pediatric orthopaedic conditions, treatment, and technology. 2020.

All that follows is from the above resource.

Abstract: Prompt evaluation of a younger child (age <5) with gait disturbance or refusal to walk is necessary to

distinguish orthopedic urgency (trauma or infection) from relatively benign processes and chronic problems such as

arthritis. Physical examination should include evaluation of gait, supine and simulated prone hip examination (on the

parent’s lap to keep the child comfortable), and the crawl test. There are six radiographic views of the lower

extremities that can assist in the diagnosis. In conjunction with the detailed history, a thorough physical exam, and

radiographs from the orthopedic provider can determine the need for laboratory tests and other imaging.Key Concepts:

• Evaluation of the limping child begins with a thorough history.

• Physical examination of the limping child can be optimized by utilizing the parent to hold the child while the examiner moves the extremities and checks the back.

• Six screening radiographs can be obtained to assist in making the correct diagnosis.

• Laboratory analysis and magnetic resonance imaging can be obtained if the diagnosis remains elusive.Onset: Acute trauma is more likely if there was a fall

and the child cried and failed to walk immediately

thereafter. If there was a delay in the onset of the limp

or pain; or history of trauma is unclear, infection or

synovitis is more likely. Additionally, the duration of

the symptoms should be appreciated in the context of the

trajectory of those symptoms. Worsening of symptoms

would add support for an infectious/inflammatory

process rather than trauma.To help determine trauma from inflammatory causes, the examiner should ask the following questions:

• Was the injury witnessed?

• Did the child cry immediately after the fall?

• When did the child start to limp—immediately?

• If the child won’t walk, will he or she crawl?

• Are there any puncture wounds?Position: The caretaker should be asked regarding the

side involved, and if the child is limping or unable to

bear weight completely. If the child is not walking, the

examiner should inquire regarding the ability of the child

to crawl. A normally ambulatory child who can crawl

has the ability to bear weight through the femur and hip

and knee, and the inability to walk is likely due to

pathology in the tibia or foot.Quality/severity: Characterization of the pain in terms of

being constant or intermittent can be beneficial. Constant

pain is more indicative of an interosseous process such

as infection or developing tumor. When there is a clear

fracture and no history of trauma given, pathological

fracture or child abuse should be considered.1,8Timing: The time of day that the pain occurs should be

obtained. Pain that wakes the child from sleep at night

suggests a more aggressive process rather than pain after

intense activity. Morning pain associated with stiffness of the joints suggests an inflammatory process, including

rheumatologic conditions.8,9A limp is any deviation of the normal gait cycle that can

appear irregular, asymmetric, laborious, or erratic. The

etiology of an abnormal gait can result from pain,

weakness, mechanical alterations, or neurologic

abnormalities. An antalgic gait is characterized by

decreased duration of stance on the affected side,

decreasing the time spent bearing weight can reduce

pain. This also reduces the stride length of the opposite

limb.6

Antalgia can present with a guarded gait that can

appear like a slow, shuffling gait, as the presentation can

occur with spine related pathology.*7

*For example, discitis.

Discitis is an uncommon condition that causes swelling and irritation of the space between the bones of the spine1. It is usually seen in children younger than 10 years and in adults around 50 years of age, and men are more affected than women1. Diskitis can be caused by an infection from bacteria or a virus1. Diagnosis is made with blood cultures and MRI studies2. Treatment is bed rest, immobilization, and antibiotics for 4-6 weeks for early infection with no abscess2.Learn more:

Physical Exam (see video)*Gait observation should be done where there is plenty of

space and the ability for the child to move without

changing the gait due to obstacles. The gait can be

observed prior to the formal history and physical, if the

examiner is able to see the child mobilize down the

clinic hallway or in the emergency department.8,10

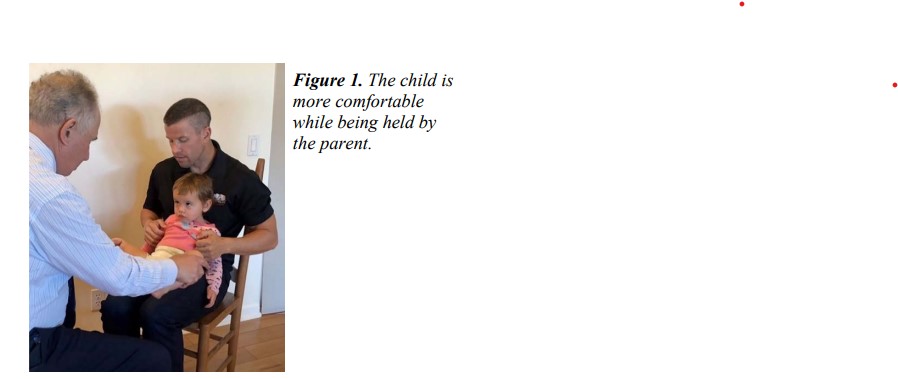

The physical examination of the child should utilize the

parent in promoting gait and providing comfort while

moving through palpation and passive range of motion

of the back and lower extremities. This portion of the

exam should be done gently and quietly on the parent’s

lap (Figure 1). In order to grain trust, the examination

should start with areas that are clearly not the source of

pathology. Palpate the back, pelvis, and trochanters, then

move distally and palpate the distal femurs, tibias and

feet. Look for knee and ankle swelling. Once the child

is comfortable in the parent’s lap, the examiner should

finally attempt to localize the area of pain. Always save

the portion of the exam that might be painful for last and

avoid any noxious tests such as blood draw for the end.

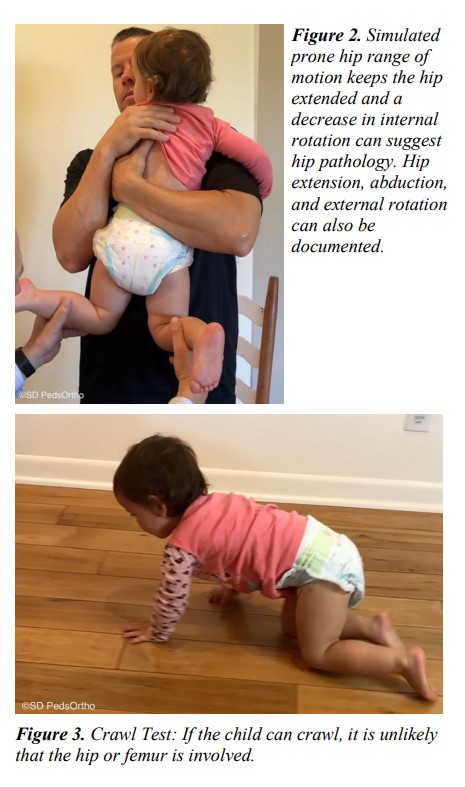

Two helpful tests are:1. Simulated prone internal rotation of the hip

(Figure 2): For the younger child, this is best done with

the child held by the parent chest to chest, with hips fully

extended. The extended position increases joint pressure

by decreasing the volume of the joint capsule.Furthermore, this position provides a more accurate

measure of the hip’s internal rotation compared to the

normal side by stabilizing the child’s pelvis. This is the

most sensitive indicator of hip joint involvement for

subacute disorders ranging from synovitis, arthritis, and

Perthes disease. Even hip flexion, extension, and

abduction can be done from this position.

2. Crawl Test (Figure 3): This will be most useful for

lateralization and localization of the pathology. If the

child will not stand, try to entice the child to crawl. If by history or by exam a reciprocal crawl is possible, the

pathology is distal to the knee. Pelvis osteomyelitis and

hip and knee sepsis are extremely unlikely in the child

who can crawl, and physical examination and imaging

studies can now be limited to the leg and feet. Examples

of pathology that limits crawling include tibia fracture,

osteomyelitis of the distal tibia, foot fracture,

osteochondritis of the foot (Kohler disease, etc.), or

foreign body in the foot.

RadiographsStart here